|

UNIVERSITY OF MAURITIUS

FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND

HUMANITIES

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS

FINA'N'Gre6rI, PZVZ.L.OMENT A'KD

Ze,ONOMIC, 9JZOWTIf: Taff 6A-SZ

OF

lZwillrl(Pf+

by DUSHIMUMUKIZA Deogratias

I n partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree

of

Master of Arts in Economics

Project Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. JANKEE

Kheswar

FEBRUARY 2010

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

DEDICATION

This dissertation is dedicated to my beloved wife Louise

MUKESHIMANA, my beloved daughter Ariane IRASUBIZA, my parents Marthe NIYONSABA,

Samuel BUGINGO and my grand parents Abel SHAMURENZI and Berne NYIRAHUKU and to

all other relatives.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

DECLARATION

UNIVERSITY OF MAURITIUS

PROJECT/DISSERTATION SUBMISSION FORM

|

Name: DUSHIMUMUKIZA DEOGRATIAS

|

|

Student ID:0826399

|

|

Programme of Studies:SH 540

|

|

Module Code/Name: MA ECONOMICS

|

|

Title of Project/Dissertation: FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENT

AND ECONOMIC GROWTH: THE CASE OF RWANDA

|

|

Name of Supervisor(s): Assoc.Prof. JANKEE KHESWAR

|

|

Declaration:

In accordance with the appropriate regulations, I hereby submit

the above dissertation for examination and I declare that:

(i) I have read and understood the sections on

Plagiarism and Fabrication and Falsification of Results found

in the University's «General Information to Students» Handbook

(2009/2010) and certify that the dissertation embodies the results of my own

work.

(ii) I have adhered to the `Harvard system of referencing' or a

system acceptable as per «The University of Mauritius Referencing

Guide» for referencing, quotations and citations in my dissertation. Each

contribution to, and quotation in my dissertation from the work of other people

has been attributed, and has been cited and referenced.

(iii) I have not allowed and will not allow, anyone to copy my

work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work.

(iv) I am aware that I may have to forfeit the

certificate/diploma/degree in the event that plagiarism has been detected after

the award.

(v) Notwithstanding the supervision provided to me by the

University of Mauritius, I warrant that any alleged act(s) of plagiarism during

my stay as registered student of the University of Mauritius is entirely my own

responsibility and the University of Mauritius and/or its employees shall under

no circumstances whatsoever be under any liability of any kind in respect of

the aforesaid act(s) of plagiarism.

|

|

Date:05/02/2010

|

|

Signature:

|

ABSTRACT

The study was intended to test the impact of financial

development on economic growth for Rwanda over the period 1964 to 2005. Four

measures of financial development are used including measures of financial

deepening and financial sophistication. We found out a significant positive

effect of financial deepening on economic growth, a bi-directional negative

relationship between financial sophistication and economic growth and no

significant evidence of the ratio of credit of banking institutions to total

domestic credit, and the ratio of credit to private sector to total domestic

credit, in promoting economic growth.

The observed failure of credit to private sector in promoting

economic growth suggests important policy implication on credit allocation

among private sector, and the failure of financial sophistication to affect

positively economic growth needs a further research on best proxies of

financial innovation in Rwanda.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Various persons deserve a vote of thanks in as far as the

accomplishment of this study is concerned. I have a pleasure to mention some of

them: I am heavily indebted to Assoc. Prof. Jankee Kheswar for his professional

guidance and advices that made this work a success.

While at the University of Mauritius, I received a lot of

assistance from staff in the Department of Statistics and Economics. These

include the Dean of the Faculty, Professor Sobhee Sanjeev, former Head of

Department of Economics and Statistics Dr. Ancharaz Vinaye and Mrs. Parveen

Salamut, the Administrative Officer. I would like to extend my heartfelt

gratitude to my lecturers in the programme, namely: Dr. V. Tendrayen-Ragoobur

and Dr. Nowbutsing M. Baboo for their invaluable knowledge they delivered

without any reserve. The same acknowledgements extend to all Lecturers of JFE.

My special thanks go to AERC and its staff for invaluable assistance on both

financial and academic side, without them this study would not exist.

I am gratefully to my colleagues, Mohamed Alie Bangura, from

the University of Botswana for the academic materials he provided whose added

value to this study can not be estimated and Marie Amanda Guimbeau from the

University of Mauritius for her kind assistance which was invaluable for

someone in a foreign country. Indeed I cannot forget to mention my colleagues

Wilson Ngyendo, Wilson K. Karuhanga, and Mustapha J. for their immeasurable

comments.

My thanks are extended to all my family members in large and

specifically my parents Marthe Niyonsaba, Samuel Bugingo, Abel Shamurenzi,

Berne Nyirahuku, my in-laws family Gaspard Munyanzira and Annonciata

Nyirabaziga for moral support they extended during my stay in a foreign

country.

I owe most profound thanks and recognition to my beloved wife

Louise Mukeshimana for the sacrifice she made by accepting our separation for

two years after one year of wedding. Without her consent, I would not have gone

for this course. May this achievement reflect the cost of her sacrifice.

In spite of all these numerous assistance from various persons,

the errors, shortcomings and opinions expressed in this study are entirely

mine.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DEDICATION ii

DECLARATION iii

ABSTRACT iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT v

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES ix

LIST OF APPENDICES x

LIST OF ACCRONYMS xi

CHAPTER 1 1

INTRODUCTION 1

1.0 Introduction 1

1.1 Statement of the problem 1

1.2 Research questions 2

1.3 Research objectives 2

1.3.1 General Objective 2

1.3.2 Specific objectives 2

1.4 Research hypotheses 3

1.5 Significance of the study 3

1.6 Scope of the study 3

1.7 Organization of the study 3

CHAPTER 2 4

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ON FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENT AND ECONOMIC

GROWTH 4

2.0 Introduction 4

2.1. Measuring financial development 4

2.1.1 Proxies of financial depth 5

2.1.2 Proxy for financial sophistication 6

2.1.3 Other measures of financial development 6

2.2 Relationship between financial development and economic

growth 7

2.2.1 Theoretical link between financial development and economic

growth 7

2.2.2 Empirical literature review on the link between financial

development and

economic growth 12

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

2.3 Conclusion 16

CHAPTER 3 17

OVERVIEW OF THE RWANDAN FINANCIAL SECTOR 17

3.0 Introduction 17

3.1. Overview over the Rwandan economy 17

3.2 The Rwandan financial sector 19

3.2.1 Banking sector 20

3.2.2 Microfinance institutions 21

3.2.3 Insurance and pension funds 22

3.2.4 Financial markets 22

3.2.5 Financial liberalization in Rwanda 22

3.2.6 Monetary policy in Rwanda 23

3.3 Comparison of financial development within EAC 25

3.3.1 Ratio of Liquid liabilities (M3) to GDP 25

3.3.2 Claims on private sector to GDP ratio 26

3.3.3 Domestic credit to GDP ratio 26

3.4 Conclusion 27

CHAPTER 4 28

METHODOLOGY 28

4.0 Introduction 28

4.1 Meaning and rationale of the model used 28

4.2 Model specification and rationale of variables 28

4.3. Model estimation 29

4.3.1 Stationarity and cointegration 29

4.3.2 Granger causality tests 30

4.3.3. Variance decomposition and Impulse response 30

4.4. The data source and measurement 30

4.5 Conclusion 30

CHAPTER 5 31

MODEL ESTIMATION AND FINDINGS 31

5.0 Introduction 31

5.1 Test for stationarity 31

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

5.2 Test for cointegration 32

5.3 Vector Error Correction Model (VECM) 34

5.4 The Engle-Granger test 36

5.5 Impulse responses and variance decompositions 37

5.5.1 Variance decomposition 37

5.5.2 Impulse response models 41

5.6 Discussion of findings 41

5.7 Conclusion 43

CHAPTER 6 44

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 44

6.0 Introduction 44

6.1 Summary of findings 44

6.2 Policy recommendations 45

6.3 Areas for further research 46

REFERENCES 47

APPENDICES 52

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

TABLES

TABLE1: TRENDS IN AVERAGE OF PER CAPITA GDP 18

TABLE 2: ADF TEST STATISTICS IN LEVELS 31

TABLE 3: ADF TEST STATISTICS WITH FIRST DIFFERENCE 32

TABLE 4: NUMBER OF COINTEGRATING RELATIONS BY MODEL, AT 5% LEVEL*

33

TABLE 5: UNRESTRICTED COINTEGRATING RANK TEST (TRACE) 34

TABLE 6: SIGNIFICANT VECTOR ERROR CORRECTION ESTIMATES 35

TABLE 7: F-STATISTICS FOR VECM 35

TABLE 8: MARGINAL SIGNIFICANCE LEVELS ASSOCIATED WITH JOINT

F-TEST 37

TABLE 9: VARIANCE DECOMPOSITION OF GRATE 38

TABLE 10: VARIANCE DECOMPOSITION OF DEPTH 38

TABLE 11: VARIANCE DECOMPOSITION OF SOPHT 39

TABLE 12: VARIANCE DECOMPOSITION OF BANK 40

TABLE 13: VARIANCE DECOMPOSITION OF PRIVATE 40

FIGURES

FIGURE 1: EVOLUTION IN RATION OF LIQUID LIABILITIES IN EAC 25

FIGURE 2: EVOLUTION IN AVERAGE OF CLAIMS ON PRIVATE SECTOR TO GDP

IN EAC 26

FIGURE 3: EVOLUTION IN AVERAGE RATIO OF DOMESTIC CREDIT TO GDP IN

EAC 27

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix A: Comparison of financial development in EAC Table A.1:

Average ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP in EAC

Table A.2: Average ratio of claims on private sector to GDP in

EAC Table A.3: Average domestic credit to GDP ratio in EAC

Appendix B: Granger causality test

Appendix C: Vector Error Correction Estimates, model 4 in Eviews

Appendix D: Impulse responses

Table D.1: Response of GRATE

Table D.2: Response of DEPTH

Table D.3: Response of SOPHT

Table D.4: Response of BANK

Table E.5: Response of PRIVATE

Appendix E: Data used in regression

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

LIST OF ACCRONYMS

ACH: Automated Clearing House

ADF: Augmented Dickey-Fuller

AERC: African Economic Research Consortium

AIC: Akaike Information Criteria

AR: Auto Regressive Models

ATMs: Automatic Teller Machines

BACAR: Banque Continentale Africaine au Rwanda

BCDI: Banque de Commerce et du Développement Industriel

(now ECOBANK) BCR: Banque Commerciale du Rwanda

BK: Banque de Kigali

BPR S.A: Banque Populaire du Rwanda, Société

Anonyme CIA: Central Intelligence Agency

CMAC: Capital Market Advisory Council

COGEAR: Compagnie Générale d'Assurance et de

Réasurance COOPECS: Coopérative d'Epargne et de Crédit

CORAR: Compagnie Rwandaise d'Assurance et de Réasurance

DF: Dickey-Fuller

DRC: The Democratic Republic of Congo (Former ZaÏre) DSA:

Development Studies Association

EAC: East African Community

EDPRS: Economic Development and Poverty Reduction Strategy GDP:

Gross Domestic Product

GNP: Gross National Product

H0: Nil hypothesis

H1: The alternative hypothesis

HQ: Hannan-Quinn criterion

I(0): Integrated of order 0 (stationary)

I(1): Integrated of order 1

IAER: Institute of Advanced Engineering and Research IFAD:

International Fund for Agricultural Development IFS: International Financial

Statistics

IMF: International Monetary Fund

KCB: Kenya Commercial Bank LDCs: Least Developed Countries

LR: Sequential modified LR test statistic

M1: Narrow money

M2: Broad money, money supply

M3: Liquid liabilities

MFIs: Microfinance Institutions MMI: Military Medical Insurance

NBR: National Bank of Rwanda OLS: Ordinary Least Squares OTC: Over- the-

Counter

RAMA: La Rwandaise d'Assurance Maladie

RWF: Rwandan Franc

SACCOs: Savings and Credit Cooperatives

SIMTEL: Société Interbancaire de Monétique

et de Télécompensation SONARWA: Société Nationale

d'Assurance au Rwanda

SORAS: Société Rwandaise d'Assurance

SSFR: Social Security Fund for Rwanda.

UBPR: Union des Banques Populaires du Rwanda (Cooperative

Bank)

UNDP: United Nations Development Program

US$: United State Dollar

VAR: Vector Autoregression Model VECM: Vector Error Correction

Model

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.0 I ntroductio

Since the views of Schumpeter (1911) on the role of financial

development on economic growth, strengthened by empirical works of McKinnon

(1973) and Shaw (1973), and invaluable contribution of Levine (1997) who

portrayed the functions through which financial development may affect economic

growth, a bulk of studies have been conducted across regions and countries to

provide further evidence on the link between financial development and economic

growth. It is in this spirit we have undertaken this study to determine whether

there is evidence of relationship between financial development and economic

growth in Rwanda.

This chapter presents the knowledge gap to be filled, research

questions and objectives alongside the hypotheses of the study. Moreover, the

chapter shows at what extend the study is relevant for Rwanda, highlights the

scope and the organization of the study.

1.1 Statement of the problem

The economic growth has been a major concern of the government

of Rwanda by putting a lot of effort to sustain Rwandan economy and to improve

social welfare. Even though Rwandan economy has recovered considerably since

the 1994 genocide; the GDP per capita is still low, around 460 US$, and over 56

percent of the population live under the poverty line. The agricultural sector,

employing more than two-third of the population is underdeveloped and its

contribution to GDP is small, accounting less than 35 percent. The industry

sector too seems not to be in a good position to be an alternative measure

since it remained on infant stage and its contribution to GDP has never reached

20 percent.

Apparently, the alternative way to speed up economic

development is through a

developed financial system. However, Rwandan

financial system remains

shallow and financial depth is below the

Sub-Saharan and East African

averages. The financial sophistication is impaired by a low

level of financial innovation though the country is being known as having above

average growth in information technology in the region. Moreover, Rwanda does

not have a developed supply of capital market-based long-term debt

instruments.

With undeveloped financial sector, it is unlikely for Rwanda

to attain a sustainable development. The purpose of this study is to find out

how the level of financial development is linked to the economic growth so as

to bring to the light, emphasis and pinpoint the crucial, critical and

paramount importance of financial development to the economic development

process of Rwanda.

1.2 Research questions

Throughout our study we will try to find solutions to the

following questions:

1. Does the level of financial development matter for Rwandan

economic

growth?

2. Is there a bi-directional influence between financial

development and economic growth?

1.3 Research objectives

1.3.1 General Objective

The main objective of this study is to assess the impact of

financial development on economic growth for Rwanda to determine whether

financial sector can be viewed as an alternative pillar for future economic

growth especially within the Vision 2020 frame work.

1.3.2 Specific objectives

1. To investigate whether the increase in credit to the private

sector had led to improvements in growth rate of GDP.

2. To determine whether the expansion of credit allocated by

banking institutions versus credit allocated by Central bank has led to

increase in growth rate of GDP.

3. To investigate whether the financial innovation has a

positive impact on GDP.

4.

To investigate whether the increase of credit to private sector

versus credit to public sector exerts a positive effect on economic growth.

5. To determine whether there is a bi-directional feedback

between proxies of financial development and economic growth.

1.4 Research hypotheses

a) The level of financial depth and sophistication positively

affects economic growth.

b) The increased share of banking institutions in credit

allocation has contributed to rise in growth rate of GDP.

c) The rise in share of credit to private sector in total

domestic credit is reflected in the growth of economic activities.

d) A bi-directional influence exists between the proxies of

financial development and the rate of growth of real per capita GDP

1.5 Significance of the study

Studies conducted on cross-sectional and panel data analyses

revealed the absence or weak link between economic growth and financial

development in developing countries. To the best of our knowledge, this is the

first study which aims to ascertain whether Rwandan country case fits with

those findings. With a weak agriculture sector and an infant industry sector,

the study will determine if a developed financial sector can be a new pillar of

Rwandan economy.

1.6 Scope of the study

The study analyses the link between financial development and

economic growth in Rwanda and covers the period of 1964 to 2005. The period

starts with the creation of the Central bank and is sufficiently long and

allows comparison with other studies.

1.7 Organization of the study

The rest of the study is structured as follows: chapter two

gives brief review of literature on the subject. Chapter three describes the

evolution of the financial sector in Rwanda. Chapter four presents the

methodology used, in chapter five we report our results and in chapter six we

conclude.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ON FINANCIAL

DEVELOPMENT AND

ECONOMIC GROWTH

2.0 I ntroductio

The causality effect between financial development and

economic growth has been a controversial issue for long years. Some researchers

have found a positive impact of financial development on economic growth,

others, in cross-country or geographical regions and income groups, have found

a significance relationship for some geographical regions and none in others,

especially for developing countries. Even though the link between financial

development and economic growth is accepted, the direction of causality is

still a debate. In this chapter, we present a review of literature on this

issue from both theoretical and empirical grounds.

2.1. Measuring financial development

We begin this section by defining what financial development

is by breaking it into two components: Financial deepening and financial

sophistication. Financial depth or deepening can be regarded as the measure of

the size of financial intermediaries. This follows the definition of McKinnon

(1973), Shaw (1973) and Levine and King (1993) where they define financial

deepening as the process which involves banking liberalization from state

control, reduction or abolition of credit rationing and marketization of

financial parameters in financially repressed economies.

On the other hand, financial sophistication is defined as the

act of creating and popularizing new financial instruments as well as new

financial technologies, institutions and markets (Tufano, 2002). The innovation

can be regarded into two areas: product or process innovation. In product

innovation, new derivatives, contracts, new corporate securities or new forms

of pooled investments products are created whereas in process innovation, new

means of distributing securities, processing or pricing transactions are

discovered and used widely.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

2.1.1 Proxies of financial depth

Many proxies have been used to measure the level of financial

depth. Some researchers simply used the ratio of monetary aggregates (M1, M2 or

M3) to GDP as a proxy of financial depth, depending on the level of financial

development of a country. This view is inspired by the work of Levine (1997) in

which financial depth was defined as the ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP.

In line with this view, Hassan and Jung-Suk (2007) used the

ratio of M3 to GDP as a proxy of financial depth. They argue that other

monetary aggregates like M1 and M2 may be poor proxies in economies with

underdeveloped financial system, where a high ratio of money to GDP exists

because money is used as store of value in the absence of other more attractive

alternatives.

Others prefer to use the ratio of money supply or the broad

money (M2) to GDP (Loayza et al, 2000). However, this measurement was exposed

to the criticism that deep financial market may cause a decrease in the M2/GDP

ratio in countries having developed capital markets. This situation can be seen

as less problematic than situations in developed countries with a dominant

banking sector (Sakutukwa, 2008).

A reasonable explanation of the weaknesses of the broad money

as measure of financial deepening has been provided by Firdu and Struthers

(2003) that with financial liberalization, capital inflows add to the funds

available for credit expansion by banking system. However, these foreign funds

do not increase money supply since they are excluded from it by definition.

Therefore, increase in credit expansion, which is a good indicator of financial

deepening, may not be reflected in the movements of the money supply in

financially deregulated economies with important capital inflows. In addition,

government borrowing from the banking system reduces the amount of credit

available to domestic private sector and may have a strong negative effect on

economic performance but this will not be reflected in the trends of money

supply.

To support challengers of the ratio of liquid liabilities as

proxy of financial depth,

Zhang et al (2007) used the ratio of claims on

private enterprise to GDP as

proxy of financial depth in investigating on the financial

deepening-productivity nexus in China over the period 1987-2001, unlikely to

previous studies in China which used M2/GDP, total credit/GDP or banking

financial assets/GDP as proxy of financial depth. They argued that as financial

sector is gradually liberalized, the rising depth of financial intermediation

is most likely to be a result of commercialization of state banks and should be

closely related to the change in the relative share of bank financing between

state owned enterprises and a variety of newly emerged enterprises. Due to lack

of data, they proposed the ratio of claims on private sector to GDP as a better

proxy of financial depth.

Karima and Holden (2001) supported this view holding that

though the ratio of liquid liabilities to GDP (or M3/GDP) indicates the level

of the liquidity provided to the economy, a weakness is that it does not

reflect the allocation of savings and so may not be an accurate indicator of

the activities of financial intermediaries. The true measure of financial depth

remains an empirical issue.

2.1.2 Proxy for financial sophisticatio

If we consider the definition provided by Koðar (1995),

that financial sophistication is brought about by financial innovations and

affects the nature and composition of monetary aggregates, it is reasonable to

measure it by the ratio of M2 to M1. This is because financial sophistication

will be characterized by introduction of credit cards, e-banking, more use of

checking accounts and all these are embodied in M2. Liu et al (1994) noted that

as the ratio of M2 to M1 increases, the more the technological improvements in

banking system.

2.1.3 Other measures of financial development

Putting aside the distinction between financial depth and

sophistication, other indicators have been added as candidate to represent the

level of financial development within a country:

Levine (1997) included three extra proxies, namely: BANK,

PRIVATE, and PRIVY, defined as follows:

>

BANK: It is the ratio of bank credit divided

by bank credit plus central bank domestic assets and measures the degree to

which the central bank versus commercial banks are allocating credit.

> PRIVATE: It is the ratio of credit

allocated to private enterprises to total domestic credit (excluding credit to

banks) and measures the level of financial services.

> PRIVY: It equals credit to private

enterprises divided by GDP.

PRIVATE and PRIVY were chosen to correct weaknesses of BANK

measure because not only financial intermediaries provide financial functions

and the volume of credit given by banks may be flowing to public institutions

which does not indicate the level of financial penetration. Unfortunately,

PRIVATE and PRIVY could not correct for the weakness of considering only

financial functions delivered by financial institutions.

Other indicators used are: Gross domestic saving to GDP

(Hassan and JungSuk, 2007), some indicators of stock market development like

stock market capitalization, turnover ratio and the number of listed companies

(Yongfu, 2005). Fry (1989) identifies three quantitative measures of financial

conditions specific to developing countries, based on McKinnon (1973) and Shaw

(1973) theories of financial liberalization. These are: the real deposit rate

of interest, population per bank branch and a financial intermediation ratio.

He added investment as percentage of GDP and change in GDP to investment ratio

as proxies of investment efficiency and net saving ratio respectively.

2.2 Relationship between financial development and

economic growth

This section goes through the theoretical and empirical

relationship between financial development and economic growth as identified by

scholars.

2.2.1 Theoretical link between financial development and

economic growth

Views on the link between financial development and economic

growth can be divided into three hypotheses: The supply leading, demand leading

and no link hypotheses.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

2.2.1.1 Supply leading hypothesis

According to this view, the financial sector deepening leads

to economic growth. The explanation is that, according to Levine (1997),

financial development has five financial functions through which it affects

economic growth. These functions, shared by Bodie et al (2008), are:

· Producing cheaper information about possible investment

and allocating capital;

· Monitoring firms and exerting corporate governance;

· Trading, diversification and management of risk;

· Mobilizing and pulling of savings;

· Easing exchange of goods and services

The effect of financial innovations on economic growth is

presented by Tufano (2002) in three functions:

· Financial innovations mitigate the lack of free

movement of funds across time and space in incomplete markets and allow risk

sharing among individuals.

· Innovations address agency concerns and information

asymmetry with invention of new contracts like common stock which provides some

mechanisms to squeeze information from firms, a warranty offered by a seller

and income bonds linked to the availability of accounting information.

· They minimize searching and marketing cost: This is the

role of ATMs, smart cards, ACH technologies and many other new businesses.

These financial functions influence savings, investment

decisions, technological innovations and hence economic growth. Better

functioning financial systems ease the external financing constraints that

impede firm and industrial expansion. This implies that the creation of

financial institutions and their services occurs in advance of demand for them.

Thus, the availability of financial services stimulates the demand for these

services by the entrepreneurs in the modern, growth-inducing sectors.

This hypothesis has received a great number of supporters:

Schumpeter (1911)

argued that the financial sector deepening leads to

economic growth through

productively making out and funding economically efficient

projects. He put emphasis on banking sector which performs the function of

intermediation between possessors of productive means and those who wish to use

them and this is a key determinant in understanding capital formation.

McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1973) developed a robust model of

financial development appropriate to LDCs, through which financial development

affects positively economic growth. Known as complementarity hypothesis, the

McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1973) model is based on the positive relationship

between real deposit rate of interest and investment, contrary to previous

thought where this link was negative. The model stresses the negative effects

of financial repression on economic growth, characterizing developing

economies.

In fact, they argue that financial repression through

interest rate ceilings, directed credit, exchange rate controls, control on the

source of finance of banking institutions and other forms of financial

repression result in negative real deposit rate of interest. This reduces the

supply of loanable funds and force banking institutions to apply credit

rationing in front of excess demand of loanable funds. The outcome is the

allocation of funds not based on the productivity of investment rather on other

factors like transaction costs and apparent risk of default. This scenario

leads to economy being allocating credit to non productive investments which

decreases investment productivity and efficiency, thus slowing down economic

growth.

Financial liberalization was proposed as a model of financial

development which leads to economic growth through increase in real deposit

rate of interest, raising the saving mobilization and the financing of the

economy both from internal and external source, as a result of capital

liberalization. This model has been a central point for analysing effect of

financial development on economic growth, where most studies compare before and

post financial liberalization periods. They include Jankee (2006) in Mauritius,

Abebe (1990) in African LDCs, Demetriades and Luintel (1996) in India, Margaret

(2004) in USA and many others.

In the same idea of financial liberalization, Fry (1997)

explained the DiamondDybving financial intermediation in an

overlapping-generations model developed by Bencivenga, Smith, Greenwood and

Smith, and Levine. With banks acting as intermediaries between savers and

borrowers, avoiding uncertainty which leads to resource misallocation and

offering liquidity to savers, they produce higher capital/labour ratios and

higher rates of economic growth.

Levine and Zervos (1996) recognise that liquid stock markets

and growth banking sector lead to economic growth through increase in capital

accumulation and production.

According to Greenwood and Jovanovic (1990), financial sector

development will direct funds to higher yielding projects with the great

involvement of information: the financial intermediaries produce better

information, improve resource allocation and hence foster growth. Basically,

the role of financial sector in easing access to information and leading to

efficient financial market raises the quality of investment, leading to

technological innovation and consequently to economic growth.

Cameron (1961) confirmed the supply leading hypothesis after

his study in France where he found a positive impact of financial development

on economic development through mortgage.

2.2.1.2 Demand leading hypothesis

The supply leading hypothesis has not received unanimity

among economists. Some influential economists such as Robinson (1952), and

Friedman and Schwartz (1963) argued that the development of the financial

sector is induced by economic growth such that it comes as a result of higher

demand of financial services. Robinson supports that economic growth creates

supply for financial services which would cause a financial development. Levine

(2001) argued that economic growth may reduce the fixed cost of joining

financial intermediaries and the more people join, hence financial sector may

be caused by improvement in economic growth.

Kuznets (1955) supports this idea by saying that finance does

not exert a significant impact on economic growth but rather when the economy

grows, more financial institutions, financial products (financial innovation)

and services come into the market in response to higher demand of financial

services. For Thanvegelu (2004), enterprise guides then finance follows.

2.2.1.3 No link or negative effect

hypothesis

This hypothesis may be regarded as the criticism of the views

above about the link between financial development and economic growth. The

footstep of this theory may be drawn for the statement of Lucas (1988), who

noted that economists have a tendency to overemphasize the role of financial

factors in the process of economic growth. It is possible that the development

of the financial sector markets may result as an impediment to growth when it

induces volatility and discourages risk unenthusiastic investors from

investing. Singh (1997) and Mauro (1995) noted that financial innovation allows

risk reduction and may lower the precautionary savings and investments, thus

slowing down economic growth.

A radical criticism of the role of financial development to

economic growth mainly through financial liberalization comes from

neo-structuralists. They refuted the model of financial deregulation developed

by McKinnon (1973) and Shaw (1973) by attacking the assumption of competitive

market in banking institutions embodied in the model. The point is that in most

developing countries, the financial industry operates in oligopolistic or

collusive model without an apparent competition as assumed by McKinnon-Shaw's

theory.

Stiglitz (1994) argued that financial liberalization leads to

market failures rooted from costly information which leads to externalities

like a generalized bank crisis following a bankruptcy in one or two banks. He

supports some measures of financial regulation like keeping interest rates

below their market equilibrium, as corrective measures which will in addition

improve the efficiency of capital allocation. In addition, financial repression

was not the only source of credit rationing.

Again Stiglitz and Andrew (1981) demonstrated that other

credit rationing may exist in equilibrium situation, as a result of other

factors outside interest rate ceilings, like asymmetry information, collusion

in banking sector which set deposit rate below the market equilibrium,

consideration of transaction costs, anticipated risk of default, quality of

collateral and pressure from bank managers.

This view has been supported by many researchers like Buffie

(1989) who stated that if we give permission to reactions in markets, then

financial liberalization will be a dangerous enterprise. Diaz-Alejandro (1985)

summarized the effects of financial liberalization as «Good-bye financial

repression, hello financial crash» because in most developing countries,

financial crisis followed financial liberalization policies undertaken by

governments and the results were worse.

Fry (1989) lists a group of neo-structuralists who questioned

the validity of McKinnon-Shaw hypothesis and demonstrated that banks cannot

intermediate as efficiently as curb markets between savers and lenders because

reserve requirements constitute a leakage in the process of financial

intermediation through commercial banks. The group includes Taylor Lance,

Sweder Van Wijnbergen, Akira Kohsaka among others.

According to them, in practice, financial liberalization is

likely to reduce the rate of economic growth by reducing total real supply of

credit available to business firms. In short, the opponents of financial

liberalization base their facts on various failures observed in many countries

after liberalization, which led to financial distress and crisis. The list of

countries is long but Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Turkey and Philippines come on

the top.

2.2.2 Empirical literature review o n the link between

financial development and economic growth

The evidence on the link between financial development and

economic growth covers a variety of studies using time series analysis,

cross-country growth regressions, panel studies, etc.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

2.2.2.1 Cross=cou ntry cases

The cross-country case studies have been carried out by many

researchers: Levine and King (1993) and Levine and Zervos (1996) found that

higher levels of financial development are positively correlated with economic

development. Their findings suggest that the legal environment facing banks can

have a significant impact on economic growth through its effect on bank

behavior.

Michael and Giovanni (2001) examined whether there is

evidence of a causal link from capital account liberalization to financial

deepening and, through this channel, to overall economic growth on

cross-section of developed and developing countries, over the period 1986 to

1995, as well as over the period 1976 to 1995. With regard to the link between

financial development and GDP growth, they noted a statistically significant

and economically relevant positive effect of open capital accounts on financial

depth and economic growth. However, this effect seems to be concentrated among

industrial countries, whereas a little evidence was found in developing

countries for financial depth brought about by capital account liberalization

to affect positively economic growth.

In Africa, Douglas (2003) investigated evidence of the

finance growth nexus in a sample of emerging Sub-Saharan African countries

using cointegration and a vector error-correction model. He found that

financial development and economic growth are linked in the long-run in seven

of eight countries and causality test revealed unidirectional causality from

finance to growth in Ghana, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Togo and Zambia.

For Ivory Coast and Kenya, the causality run from growth to finance, confirming

the demand leading hypothesis in the two countries.

2.2.2.2 Panel data cases

Starting by Africa, Kesseven et al (2007) brought new

evidence of finance-growth relationship from developing countries by analyzing

a sample of 44 African countries from 1979 to 2002. They used both static and

dynamic panel analysis and random effect and found that the financial

development has been contributing to the level of output though the

contribution was not at the same

level across countries. However, the contribution of financial

development was observed to be on the lesser extent as compared to the other

explanatory variables.

Karim and Holden (2001) conducted a panel of 30 developing

countries to test the supply leading hypothesis. Using the alternative measures

of bank development and stock market development, they found a strong positive

link between stock market development and economic growth. However, contrary to

the findings of Levine et al (2000), they found a negative association between

credit allocation and economic growth. The reasons were the failure of

financial deregulation due to absence of prerequisites for successful

deregulation.

Fry (1989) examined over 15 years saving behavior in 14 Asian

developing countries and 28 developing countries heavily indebted to the World

Bank. It was found that a 1 percent rise in real deposit rate of interest

raises national saving ratio by about 0.1 percent. On the effect of financial

liberalization on investment productivity, Fry found positive and significant

relationship between the incremental output/capital ratio and the real deposit

rate of interest and also the real deposit rate of interest and economic growth

in those Asian developing countries.

2.2.2.3 Country case=studies

Spears (1991) examined the causal relationship between

financial intermediation and economic growth in a sample of five Sub-Saharan

African countries (Burkina Fasso, Cameroon, Ivory Cost, Kenya and Malawi),

using Granger causality and two-distributed-lag regressions. He used two

measures of the financial development: the ratio of money supply to real per

capita GDP and the ratio of quasi-money to money supply. He found no causality

between the later and economic growth and these results may be attributable to

wrong measure used rather than absence of causality between financial

development and economic growth. But the causality from financial development

to economic growth was found when the ratio of money supply to GDP was used.

Team (2002) used a VECM in 13 Sub-Saharan African countries

and found from the cointegration analysis that there exists a long-run

relationship between financial development and economic growth in twelve out of

thirteen countries and the causality run from finance to growth in eight of the

countries taken in the sample. Six countries provided evidence of

bi-directional causality.

Demetriades and Luintel (1996) found a bi-directional

causality between financial deepening and economic growth in India and a

negative impact of banking sector control on economic growth, in the model

linking financial depth and banking deregulation to economic growth using Error

Correction Model. Zhang (2007) examined if regional productivity growth is

accounted for by the deepening process of financial development in China, using

provincial panel data, and found that after controlling for other variables,

the depth of financial intermediation exerts significantly positive influence

on productivity growth in China during 1987-2001. The financial

intermediation-growth nexus in post reform China was strongly supported.

2.2.2.4 Industry and firm level case studies

Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic (1998), in a firm

level data, showed that larger banking systems and more liquid stock markets

allow firms to grow faster than it would be had been internal resources used to

finance their investments. Using industry level data across countries, Rajan

and Zingales (1998) found that external finance benefits more to their users

and allows firm to grow faster than firms which only resort to domestic

financial markets.

A different approach was taken by Beck et al (2006) by

examining the effect of the size of the industry in financial

development-economic nexus. Using industry data, they concluded that economies

dominated by small firms grow faster in developed financial system than large

firm-based economies.

Raymond and Love (2004) used data of 37 industries in 43

countries over the period 1980-1990, to analyze the link between financial

development and interindustry resource allocation in the short and long-run,

and found that in the short-run, financial institutions allocate resources to

any industry that has experienced a positive shock to growth opportunities

irrespective of his source

of financing, whereas in the long-run, in countries with well

developed financial institutions, industries which rely heavily on external

financing (Debt-finance instead of equity-finance) will have a comparative

advantage and will capture a larger share of total production in the

economy.

2.3 Co nclusio

The chapter examined three theoretical views about the link

between economic growth and financial development: the one stating that the

financial sector development leads to economic growth, another putting economic

growth ahead of financial development and lastly the view which does not

support the importance of financial development on economic growth. On the

empirical side, a strong positive role of financial development on economic

growth has been found mostly in developed countries, and a weak or absence of

link in developing countries. In some cases, the demand leading hypothesis has

not been supported. In the next chapter we present the Rwandan financial

sector.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

CHAPTER 3

OVERVIEW OF THE RWANDAN FINANCIAL SECTOR 3.0

Introduction

This chapter narrows the financial development issue to

Rwandan case and highlights the weaknesses as well as the strength of the

Rwandan financial system. To situate the level of financial development in

macroeconomic perspective, a brief review of Rwandan economy is first

presented. The chapter finishes with a comparison of the financial sector in

Rwanda with those of other country members of East African region where Rwanda

and Burundi were admitted in 2008.

3.1. Overview over the Rwandan economy

Rwanda is a small landlocked country in Central-East Africa,

with 26,338 square kilometers. Its GDP per capita was $ 62.95 in 1970 with a

population of 3.7 million, eight years after its independence from Belgium in

1962. The country is hampered by mountainous terrain and distance from the

sea.

Rwanda is among most densely populated countries in Africa.

In 2009, Rwanda was ranked 29th among densely countries in 239

countries with density of 379 people per square kilometer, far ahead of the

African average of 34 people per square kilometer. In 2009, the population was

9.998 million, growing at 2.8 %, compared to African average of 1.66 %, thus

putting increasing pressure on agriculture land and environment (United Nations

Population Division, 2008).

Rwanda's economy is essentially rural; nearly 81% of the

population lives in rural areas (United Nations Statistic Division, 2009) and

derives its livelihood from subsistence agriculture, cultivating coffee and tea

for export with rudiment methods. Besides agriculture, there is exploitation of

scarce natural resources in some regions like cassiterite, wolframite, and

methane recently discovered in Lake Kivu.

Rwandan economy has been improving since 2000 with an

increasing growth

rate especially for the last four years, when the country

maintained an average

growth rate vis-à- vis many African countries over the

period 2005-2008. In fact, the growth rate was 7.2 % in 2005, 7.3% in 2006, 7.9

% and 11.2 % in 2007 and 2008 respectively accumulating into an average growth

rate of 8.4 % above the African average rate of 5.82% during this period. In

addition, the country became the third, after Angola and Ethiopia (IMF, 2009).

Moreover, Rwanda has made considerable efforts in improving living conditions

of her population. Poverty has fallen by 3%, from 60% of the population living

under the poverty line in 2000/2001 to 56.9% in 2006 but leaving 37.9% still

extremely poor (IFAD website). However, Rwanda's development indicators are

still below the African and East African averages, as indicated by the table

below:

Table1: Trends i n average of per capita GDP

Indicator

|

Country

|

1970=

1980

|

1981=

1990

|

1991=

2000

|

2000=

2008

|

Overall average

|

Per capita GDP (in US$)

|

Rwanda

|

147.4

|

323.5

|

268.2

|

276.6

|

250

|

|

489.21

|

768.9

|

733.9

|

1029.8

|

734.59

|

|

232.45

|

313.9

|

278.8

|

346.76

|

288.69

|

Growth rate of GDP (%)

|

Rwanda

|

5.54

|

2

|

3.2

|

7.13

|

4.36

|

|

3.08

|

3.26

|

3.17

|

5.27

|

3.55

|

|

3.87

|

2.14

|

2.82

|

5.83

|

3.5

|

Share of Gross capital formation in GDP (in %)

|

Rwanda

|

14.45

|

18.71

|

13.35

|

17.27

|

15.84

|

|

29.80

|

26.07

|

20.05

|

24.26

|

25.32

|

|

22.29

|

17.77

|

16.26

|

19.15

|

18.94

|

|

Source: Author's calculations from data

provided by United Nations Statistics Division, CIA World Fact books and World

Development indicators Database.

As the table indicates, for the period 1981-1990 Rwanda

reached the highest average per capita GDP with $323.5 compared to the average

of $276.6 during the recent period ranging from 2000-2008. In addition, it is

only in this period where its per capita GDP and the share of Gross capital

formation in GDP was

above East African average. This was mainly due to political

stability and favorable weather that prevailed during that time which made

agricultural sector to contribute a lot in GDP.

The period 1990-2000 was marked by war of four years

(1990-1994), the genocide of 1994 in which more than one million lost their

lives and insecurity which affected the north (1996-1998). This explains the

decrease in above indicators. Despite this situation, the growth rate of GDP

exceeded African and East African average, as the country was trying to

recover. Although the recent period was marked by the highest per capita GDP in

2008 with $ 458.49, but the period was characterized by a low per capita GDP in

the period ranging from 2001-2003, a figure less than $200.

It is worth to say that it is in 2008 where the country

recovered and passed over the level of per capita GDP reached before the

genocide, that of 1988 with $360.87. The per capita GDP has been declining as

from 1989, one year before the beginning of the war of 1990, up to 1994 from

$360.87 in 1988 to $207.43 in 1994. Since 1995, the economic growth started to

recover and currently, though the per capita GDP is still low, but Rwanda is

among top performing in Africa with the growth rate currently above both

African and East African average.

Many reasons explain the poverty of the country: being a

landlocked country, on this it added the bad governance which has characterized

the country since its independence, war, genocide and insecurity, lack of

natural resources, little skilled human capital, as per year 2005, less than 1%

of the population had a tertiary education, and a low level of investment.

3.2 The Rwandan financial sector

We analyse the financial sector by looking at the banking

sector, MFIs, insurance companies and financial markets. We begin by mentioning

that the Rwandan financial sector can be traced back from the creation of the

Central Bank, National Bank of Rwanda and issue of the local currency, Rwandan

Franc (RWF) in April 1964.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

3.2.1 Banking sector

The development of the financial sector before the genocide

of 1994 was slow. At the time, only 3 commercial banks and 2 specialized banks

operated with a total of less than 20 branches in the country, and one

microfinance (UBPR) with around 146 branches. The war and the genocide affected

heavily the banking sector: The genocide itself resulted in closure of the

Central bank for 4 months. The former government left the country in 1994 for

the DRC, after committing the genocide, with two-thirds of the national

monetary base in addition to US $7 million in cash which was taken from the

UBPR (Alson et al, 2001). Consequently, it took two years for this bank to

reopen, in 1996. Moreover, almost both physical and human capital of all banks

were destroyed during the genocide.

The post genocide period was marked by increase in number of

banks, where in 2002 there were 6 commercial banks with 28 branches, 2

specialized banks and 1 union of financial institutions (UBPR) with 148

branches (NBR, 2004). In 2007, commercial banks operated only 38 branches,

making only 7 % of all branches of financial institutions and by the end of

2008, 8 commercial banks, 2 specialized banks and 1 Microfinance bank were

operating.

However, there was a lack of competition as three banks (BCR,

BK and ECOBANK) held 66% market share before the licensing of UBPR as

commercial bank in 2008. This situation has led to high interest rate spreads

(8.6% in 2005), a modest 16% per annum growth in deposits over the past 5

years, and lending primarily to a core group of about 50 relatively large

customers concentrated in Kigali and a few sectors (Murgatroyd et al, 2007).

The penetration of banking sector is very low, and worse in

rural areas. The survey conducted by FinMark Trust in 2008 showed that in

general, only 14 percent of the active population use banks, 7% use MFIs, 26%

are informally served and 52% are financially excluded. In rural areas, less

than 6 percent of the population hold savings account in a formal finance

institution. Indeed, penetration of domestic credit to the private sector is

underperforming, with 11

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

percent of GDP, compared to 18 percent of GDP for peer countries

(NBR, 2008).

Several reasons explain the underdevelopment of financial

services. The weak culture of savings among the people is due to low level of

per capita income in the country. In fact, in 2009 Rwanda was ranked

21st poorest of the least developed countries in the world and 56.9

percent of its population lives on less than US$0.45 equivalent a day, the

poverty threshold in Rwanda (IMF, 2009).

Secondly, a high spread between the deposit rate (around 7%)

and a lending rate (around 16%) does not provide an incentive to the public to

save. Many bank accounts are used as a payment mechanism for employees. It is

important to note that due to relative higher penetration of UBPR, it has been

upgraded to commercial bank in 2008 and became BPR S.A, and that KCB, a new

regional bank from Kenya has been licensed.

3.2.2 Microfi na nce institutions

Microfinance initiatives mushroomed from 2002, primarily as a

response to the weak involvement of the traditional banks in small and micro

enterprises, and rural areas. Sixty-three microfinance institutions were

licensed in 2006 (Habyalimana, 2007).

In 2009, the microfinance sub-sector consisted of around 125

MFIs including 111 COOPECS (Kantengwa, 2009). In June 2006, NBR estimated that

MFIs represented 24.18% of the total financing of the economy with RWF 59bn

(equivalent of $100 million) out of RWF 244bn of credit of the financial

institutions and 25% of savings mobilization. The mobilized savings amounted to

RWF 65bn (equivalent to around $.110 million) out of RWF 259bn. Informal

finance is so popular that 73 % of total population reported using informal

loans in 2005 (Habyalimana, 2007).

However, Microfinance institutions are inexperienced,

characterised by management with poor corporate governance, weak information

systems, important losses caused by poor internal organisation and a

mismanagement of their loan portfolio (Kantengwa, 2009). All these weaknesses

culminated into

the failure of nine microfinance institutions in 2006 with

total deposits of more than $5.3 million, leading to a general panic (NBR,

2007). To include rural population in the financial system, UMURENGE SACCOs was

introduced in the end of 2008, a saving scheme to be operating in each of 421

sectors.

3.2.3 Insurance and pension funds

This sector comprises 5 classic insurance companies (SONARWA,

SORAS, COGEAR, CORAR and Phoenix of Rwanda Assurance Company) and six insurance

brokers. In 2006, only about 3% of the active population held insurance policy.

In addition, there are three public medical insurance companies: RAMA, MMI and

Mutuelle de Santé and one private company, AAR Health Services, licensed

in 2008. The relatively well performing RAMA and MMI serve only 5% of the

population (NISR, 2008).

The pension sector is assured by one Public Pension fund

(SSFR) and 10 Growing Private Pension funds. The SSFR covers only 7.5% of

active population and on overall less than 8% of the active population is under

pension schemes (NBR, 2009).

3.2.4 Financial markets

In January 2008, Rwanda established a capital market with the

creation of an Over-The-Counter market operated and regulated by a Capital

Market Advisory Council (CMAC). However, its market capitalisation is still

very low as only $ 360, 000 has been traded in 15 transactions (the average of

$24,000 in each transaction) and newspapers frequently reported that the OTC

has been silent due to lack of transactions recorded. The main reason is the

poverty of Rwandan citizen which does not allow the culture of saving where

even those who earn monthly salary are able to spend it for survival only. With

regard to market participants, Rwandan OTC has 7 members divided into three

categories: Stockbrokers, Dealers and Sponsors (CMAC website).

3.2.5 Financial liberalization i n Rwanda

Before the financial liberalization, tools of monetary policy

were mainly credit

rationing, directed credit and interest rate controls.

The financial deregulation

was characterized by legal reforms affecting the nature of

central bank supervision and new tools of monetary policy were introduced like

regal reserve requirements and discount rate, alongside the abolition of

interest rate ceilings, directed credit and credit rationing as well.

The process of financial liberalization started in March 1995

by the liberalization of exchange rate and interest rate in 1996. In the same

year, banking structure was opened to foreign investment and entry requirements

for MFIs were relaxed. However, despite abolition of controls on interest

rates, the rigidity in the later is still observed, fluctuating around 16% for

lending and 7% for deposit rates of interest, due to oligopolistic nature of

the banking system.

The period 2004-2006 was characterized by take over of

nonperforming banks due to poor corporate governance. BACAR and BCDI were taken

over by FINABANK and ECOBANK respectively, and the government sold its majority

of share in BCR. In 2006, the spread of MFIs nationwide came as another step in

financial liberalization, following the failure of commercial banks to deliver

in rural areas. However, as prophesized by Diaz-Alejandro (1985), the end of

2006 and 2007 turned the financial sector in crisis as consequence of

unmonitored regularization, after which the central bank started exerting basic

controls on financial institutions through micro finance law and regulation

adopted in 2008, and strengthened by creation of MFI association created in

2007.

3.2.6 Monetary policy i n Rwanda

Monetary policy is a responsibility of the NBR and is a part

of the annual economic program aiming at implementing the medium-term program

referred to as EDPRS. Like all central banks, NBR uses open market operations,

reserve requirements (fixed at 8% before 2009 and reduced to 5% from 2009), and

discount rate (which fluctuates between 7.5 % and 8%). With its basic objective

of price and foreign exchange stability, its development can be regarded in two

periods: the period of financial regulation, from 1964 to 1995 and after

liberalization in 1995.

Before 1995, the country was in fixed exchange rate regime.

From 1970 to 1990, the foreign exchange rate was 1$ for nearly 82 RWF. However,

the war period 1990-1994 saw many devaluations, especially that of 1991 with

51.5 % and that of 1994 of 91.64% and by the end of 1994, the exchange rate

stood at 1$ for 220 RWF (DUSHIMUMUKIZA, 2006).

The period of flexible exchange rate was characterized by

volatility in exchange rate. As evidence, in January 2003, the average exchange

rate stood at 511.2168 RWF for 1$, but by end of the year, the exchange rate

was at 574.83RWF for 1$. The depreciation rate stood at 11.6% from one year to

another. If we compare the average exchange rate of 2002 and 2008, the index is

115.2 in six years, from the exchange rate of 475.32 FRW for 1$ in 2002 to

547.61 FRW for 1$ in 2008 (NBR, annual report, 2008). Indeed, this exchange

rate can be compared to 220 RWF for 1$ in 1994.

Regarding price stability, again the rampant inflation

characterized the after liberalization period, as compared to the period before

where the price stability was observed. Evidence from Kigali (the Capital city)

in 2003 shows that the CPI for all products in constant terms of 1982 was

559.32 compared to the CPI of 408.93 and in 1996 (NBR, annual report of 2003).

The inflation rate is fluctuating around 7.5%

For money supply, there was an upward trend in money supply

to the level where its growth rate was above that of GDP. For instance, in

2007, increase in money supply was 31.25% against 13% of nominal GDP. Indeed,

in some years, the money supply experiences an over expansion, especially

during election periods like 2003 and 2008.

For payment system monetization, SIMTEL was introduced in

2005 aiming at speeding up the level of financial innovation, which is very

low, as in 2008 the value of transactions using bank cards was 0.59 percent of

the non cash payment instruments (dominated by cheques) and cash payment

represented 98% of the payment system (NBR, 2009). Introduction of Real Time

Gross Settlement and an Automated Clearing House were few among mechanisms of

such modernization.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

3.3 Comparison of financial development within

EAC

The discussion omits comparison based on the number of

financial institutions as the countries are not equally sized and formal

financial markets since Rwanda and Burundi do not have them while Kenya

launched its stock market (Nairobi Stock Exchange) in 1954 and those of

Tanzania and Uganda are operational since 1998. We rather use some ratios

regarded as proxies of the level of financial development.

The need for this comparison lies in the sense that the

macroeconomic policies of these countries are tied together, hence it pays for

Rwanda to know its status quo in this community of countries. Three indicators

are used: Liquid liabilities as % of GDP, claims on private sector to GDP ratio

and domestic credit to GDP ratio. Data which are sources of the figures are

presented in appendices.

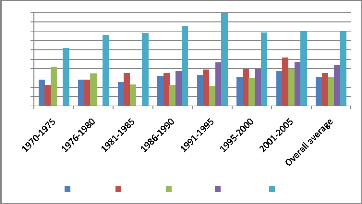

3.3.1 Ratio of Liquid liabilities (M3) to

GDP

Rwanda and Uganda are the last and their M3/GDP ratio are far

below the average of the AEC (21.98 % of GDP) with Kenya leading at 39.77%

compared to 15.35% of Rwanda, as shown by the chart below:

45

40

25

20

50

35

30

15

10

0

5

Rwanda Burundi Uganda Tanzania Kenya

Figure 1: Evolution i n ration of liquid liabilities i n

EAC

On overall, Kenya comes first followed by Tanzania, Burundi,

Rwanda and Uganda. We noted that in 2005, worldwide ranking of these countries

were: Kenya 94th, Tanzania 113rd, Burundi

118th, Rwanda 131st and Uganda 132nd out of

173 countries, with weighted average of 58%.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

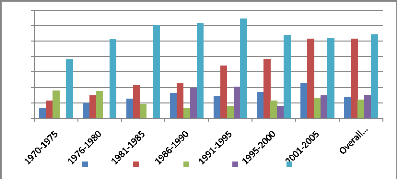

3.3.2 Claims o n private sector to GDP ratio

This indictor was suggested by some researchers as the best

measurement of the level of financial depth as discussed in chapter two. The

figure below indicates the level of financial depth in East African Countries

had been this indicator used.

35

30

25

20

15

10

0

5

Rwanda Burundi Uganda Tanzania Kenya

Figure 2: Evolution i n average of claims o n private

sector to GDP i n EAC

Kenya is still leading followed by Burundi whereas other

countries are almost at the same level, which is very low below the average of

14.75%. Rwanda is the fourth with 7.05% while Uganda is the last in the group

with 6.11%. Based on this indicator, we can say that Kenya enjoys a financial

deepening four times that of Rwanda. However, Rwanda has been improving but at

a slow rate compared to Burundi which made a significant improvement. This

ratio for Burundi was more than three times that of Uganda and more than double

that of Rwanda in recent period, while 30 years ago the difference between

these countries was slightly small (less than 3%).

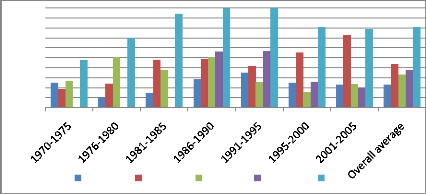

3.3.3 Domestic credit to GDP ratio

As the next figure shows, Burundi has been improving

considerably from the last in row during the period 1970-1975 (with 9.45 %) to

the 2nd position (with 36.62%) for last two consecutive periods,

from 1995 to 2005. Surprisingly, this indicator declined considerably in

Rwanda's post genocide where it moved from 17.51% as the average for the war

period of 1990-1995 to 11.54% for the last period 2001-2005 while the country

was supposed to be putting enough effort in the credit to private sector to

speed up the economic growth.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

45.00

40.00

50.00

35.00

30.00

25.00

20.00

15.00

10.00

0.00

5.00

Rwanda Burundi Uganda Tanzania Kenya

Figure 3: Evolution i n average ratio of domestic credit

to GDP i n EAC

This ratio for Rwanda was below the EAC average throughout

the period. Moreover, there is an increasing gap between Rwanda, the last in

group, and Kenya, the first, from 11.46% over the period 1970-1975 to 27.97%.

This is one among reasons that explain the gap in the level of economic

development among these countries. Uganda and Tanzania too have the low ratio.

Though several reasons can explain why Rwanda is lagging behind in financial

development, civil war, insecurity and poor governance are paramount factors to

the explanation. However, a detailed analysis is needed to explain why Tanzania

and Uganda are not performing well in some areas while they enjoyed a relative

stability, contrary to Burundi which was in war since 1993 up to 2005 and

performed well.

3.4 Co nclusio

Rwandan economy has been growing during post genocide period

but still the economy is at the lower level when compared to other countries.

Indeed, the financial development is still low and below the average of the

East African countries. When considering some indicators of the financial

development over the period 1970-2005, Rwanda is almost the last within five

countries though Uganda and Tanzania too are not performing well. This

observation brings to mind the empirical question of the extent to which the

level of financial development in Rwanda is linked with the level of economic

growth. Therefore the following chapter presents the methodology followed to

conduct this study.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

CHAPTER 4

METHODOLOGY

4.0 I ntroductio

This chapter presents the methods and techniques, the model,

estimation techniques and types of data used in this study in investigating the

causality among the proxies of financial development and economic growth.

4.1 Meaning and rationale of the model used

The use of VAR was motivated by its ability to capture the

dynamic interaction of financial sector development and economic growth. A VAR

is a direct generalization of the univariate AR(p) model to the case of a

vector of variables and is used to express the dynamic correlations between the

variables and hence is considered as an alternative to large-scale simultaneous

equations structural models (Brooks, 2008).

It allows treating each variable as endogenous thus avoiding

restrictions, judged incredible by Sims (1980), imposed by univariate AR, by

specifying some variables as being exogenous. This model was chosen because the

changes in indicators of financial development are possibly correlated with the

disturbance term in the equation of economic growth. This is because an

unobserved factor that influences growth of GDP may very well influence

indicators of financial development, making them endogenous. Further more, this

study joins other studies on the matter which used the VAR frame work, namely:

Hassan and Jung-Suk (2007); Teame (2002); Sakutukwa (2008) and others.

4.2 Model specification and rationale of

variables

In a VAR model, all variables have equations linking the

change in that variable to its own current and past values and the current and

past values of all the variables in the model, as it describes the dynamic

evolution of a number of variables from their common history (Verbeek, 2004).

The model is expressed

in a matrix form as:Yt = B +

Elic_i AtYt_i + Et with:

V, = ( GRATES

DEPTHBANKPRIVATESOPHT )

Yt : It is a 5×1 column vector of 5 variables

including proxy measures of the financial development, B is a 5×1 column

vector of constants, At and

Yt_i are

5×5 matrices of coefficients and lagged variables

respectively, i is the lag length

to be determined by AIC criteria and et is a 5×1

column vector of error terms. Variables included in the models are:

GRATE = Growth rate of Real per capita GDP, following the works

of Sinha and Macri (2001) and Kesseven et al (2007);

DEPTH = Claims on Private sector to GDP ratio considered as

proxy of financial deepening, following the works of Karima and Holden (2001),

Firdu and Struthers (2003) and Zhang et al (2007);

BANK = Domestic credit by deposit money bank and other banking

institutions divided by total domestic credit;

PRIVATE = Claims on the non-financial private sector to gross

domestic credit; SOPHT = Ratio of broad money to narrow money (M2/M1) as proxy

of financial sophistication, following the work of Sakutukwa (2008).

BANK and PRIVATE are inspired by the work of Levine and King

(1993). Unlike to them, we have included the domestic credit for other banking

institutions in BANK to mitigate the drawbacks of this indicator as commercial

banks are not the only financial institutions to provide valuable financial

functions. However, there is still a weakness in these proxies in Rwanda

because data used on assets of financial institutions do not include the UBPR

which play an important role in Rwandan financial sector.

4.3. Model estimatio

4.3.1 Statio narity and coi ntegratio

Due to spurious regression resulting from nonstationary

series in the regressions, we have conducted the tests for stationarity, using

ADF to check whether the residual series are white noise. The tests for

cointegration have been conducted to determine the form of the VAR to be

estimated. In fact, trend stationary variables are estimated by OLS, if the

variables contain stochastic trends and cointegrated, a VECM is used and

finally if the variables are not stationary and not cointegrated, the model is

estimated after the stochastic

trends have been removed by taking first differences of the data.

All tests were run within Eviews 6.

4.3.2 Granger causality tests

To determine which sets of variables have a significant

effects on each dependent variable, causality tests have been conducted by

restricting the coefficient of the lags of a particular variable to zero

(Wooldridge, 1990). The objective is to find out if changes in one variable do

affect changes in another variable and vice versa. If this is the case, as

explained by Brooks (2008), a sets of lags of the included variable should be

significant and it would be said that there is a bi-directional causality,

otherwise it should be said that some included variables are exogenous or no

causality exists at all between variables had been all lags insignificant.

4.3.3. Variance decomposition and Impulse

response

The ambiguity in interpreting individual coefficients in VAR

model (Gujarati, 2004) motivated us to use the variance decomposition and

impulse response function which trace out the response of the dependent

variable in the VAR model to shocks in the error term for several periods in

the future, keeping constant all other variables dated t and

before.

4.4. The data source and measurement

The five considered time series are ratios we have computed

from data provided by the IFS Yearbooks. The database includes 42 annual

observations from 1964 to 2005. Unlikely to previous studies which used natural

logarithm of the series, we did not find any graphical relationship, as advised

by Gujarati (2004), which motivates a priori transformation of the data to

log-log model.

4.5 Co nclusio

This chapter has presented the methodology that has been used

in this study. The next chapter presents and analyses the results of

econometric estimation. The main objective of the chapter is the hypothesis

testing.

Financial Development and Economic Growth in Rwanda

CHAPTER 5

MODEL ESTIMATION AND FINDINGS

5.0 I ntroductio

So far we have presented the literature both on theoretical

and empirical side on the causality between economic growth and financial

development. It is now time to turn to the empirical testing of this

relationship for Rwandan economy. This chapter presents the results obtained

from econometric testing and discusses the meaning and reason behind the

figures.

5.1 Test for statio narity

The footstep of this analysis is to determine whether the

series are stationary or not. The ADF was used to test for stationarity of

these series as it provides a superior test to DF, especially in case the

residuals of the regression could be serially correlated. The lag length has

been automatically selected by AIC from nine proposed lags and all three