2 Background: Sanitation and

Marketing

In this dissertation, the term of «sanitation» refers

to excreta management, which is one part of environmental sanitation.

Environmental sanitation comprises the safe disposal

of human excreta, wastewater and rainwater, and solid waste

(Cairncross & Feachem,

1993). The excreta management part comprises the following

aspects:

· The safe separation of faeces from the human body,

· The containment of faeces (for instance in a pit),

· The transport of excreta from the containment to a

disposal site,

· The final disposal of excreta, or its reuse and

return to land.

The last point is subject to debate, in order to consider a

sanitation system «ecological»

or not (see Winblad & Simpson-Hébert, 2004). This

literature review develops several aspects of sanitation which are relevant to

the research. First, different approaches of sanitation are considered

(Section 2.1), Section 2.2 presents in more detail the concepts behind

sanitation marketing, and the particular problem of pit emptying in urban

areas

is finally reviewed in Section 2.3.

2.1 Approaches to sanitation

Sanitation has been approached in various ways in the past. The

stress is now put more

on «sustainable sanitation» and «improved

sanitation» as proposed by the MDGs and

the Water and Sanitation Programme (WSP). If «improved

sanitation» is clearly defined

by the WSP (as including sewer / septic tanks / pit latrines,

but excluding bucket, open and public latrines, see WHO-UNICEF, 2000),

«sustainable sanitation» remains a blur concept, for which

definitions are hard to find in literature. An attempt to define it is

presented in Appendix D on page 70, extracted from Jenkins & Sugden

(2006).

For Black (1998), the last 30 years can be divided in several

types of approaches for water and sanitation programmes. The «appropriate

technology» phase from 1978 to

1988 focuses on low-cost technologies, mostly proposed by

engineers from developed countries; the Water and Sanitation decade introduced

then a change from hardware to

software between 1988 and 1994. As the urban sanitary crisis was

growing, policies

have also changed to more demand-responsive approaches and

capacity building.

The following Sections present some of these approaches.

2.1.1 Supply-driven approaches

Latrine construction programmes driven by the supply side are

still frequently found. Mukherjee (2000) claims that many failures in past

sanitation projects come from «myths»: that sanitation coverage

directly has a health impact (while it requires also some be- haviour change),

that demand-responsive approaches do not work for sanitation (while

they seem even more important than for water projects), that

water supply and sanitation should always come as a «package» (but

users perceive it often very differently, and the levels of demand are rarely

similar).

For Klundert & Scheinberg (2006), sanitation is too often the

«poor parent» of water programmes, which adopt «the well-known

rural water and sanitation approach». Jenk-

ins & Sugden (2006) criticise this integration with the

water supply side by noting the differences in timescale, decision-making

processes, time to create demand and skills required between water supply and

sanitation.

The question of subsidy is also criticised (ibid.), as

incorrectly applied subsidies cre-

ate dependency, poor use of public money, absence of replication

and affordability, and often the inability to reach the poor.

2.1.2 Ecological sanitation

Ecological sanitation (or «eco-san») is based on

three principles: preventing pollution rather than trying to control it,

sanitising the excreta, and re-using it for agricultural purposes (Winblad

& Simpson-Hébert, 2004). Several systems exist for this purpose,

all transforming human excreta into compost, such as

double-vault dehydrating toilets, biogas production systems, the Arborloo, etc.

For Morgan (1999), «Ecological sanita- tion is a system that makes use of

human waste and turns it into something useful and valuable with a minimum of

risk of pollution of the environment and with no threat to human

health.»

Supporters of ecological sanitation claim that it can address

many of the issues of urban development, such as water pollution, food

insecurity, low income and of course poor sanitation facilities (Winblad &

Simpson-Hébert, 2004). It is however criticised by Klundert &

Scheinberg (2006) based on experiences in African cities, for three reasons:

ecological sanitation is largely based on the willingness from the users to

handle dry

faeces, which is far from evident in most cities1;

many systems are based on urine

1 Even Winblad & Simpson-Hébert (2004)

acknowledge that «faecophilic societies» are rare and quote

only rural China as being «faecophilic»

separation, yet urine is rarely collected and ends up polluting

the groundwater; other

on-site sanitation systems are often used in parallel with

eco-san, ecological toilets do not fill up and are rarely emptied.

Sugden (2006) classifies ecological latrines in five types. Of

these five types, only two latrines do not imply urine separation (the double

pit composting latrine and the single

pit walking latrine), and only one does not rely on manual

handling of the composted faeces: the single pit walking latrine, also known as

the Arborloo.

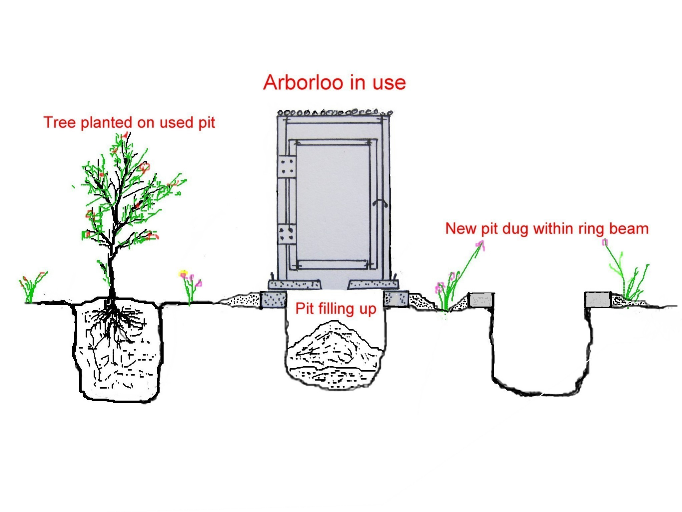

The Arborloo

Quoting Sugden (2006):

«This is the simplest type of latrine and the one that

involves the least amount of behaviour change from the conventional pit

latrine. Anybody who has planted a tree in a full latrine pit can be said to

be practising eco- sanitation.

A shallow pit (1.2 m recommended) is dug and a slab and easily

movable superstructure placed on top of it. The family uses the latrine,

adding the mixture of soil and ash after each use, until it is three quarters

full (usually between 4 and 9 months). After this the slab and the

superstructure are moved to another pit. A layer of soil is added to the full

pit and a sapling placed into the soil. The tree grows and utilises the

compost to produce large, succulent fruit. After a few years of latrine

movement the result is

an orchard that is producing fruit with a real economic value.

The super- structure can be made from any locally available materials e.g.

grass, reeds etc.»

See Figure 2.1 below for its representation. The Arborloo can

have the following im- pacts:

· Safe excreta disposal with associated health

improvements

· Improved nutrition due to better food supply

· Improved livelihoods from sale of excess crop

· Mountain slope stabilisation from fruit tree root

· Increased organic matter in soil assisting soil water

retention.

However, it still relies on the presence of urban agriculture,

sufficient space for digging

the pits, and the lack of reluctance from the users to eat food

which has grown using such a fertiliser.

Figure 2.1: The Arborloo

2.1.3 Total sanitation

The Total Sanitation Campaign (TSC) is an alternative

developed in India, for rural ar- eas, by the Department of Drinking Water

Supply (DDWS, 2005). Its aim is to eradicate open defecation and improving

sanitation facilities with no or low subsidy, by using par- ticipatory tools

within the community to create change and raise demand for improved sanitation.

Reports claim that this option can achieve 100% coverage in a community

(ibid.), yet it is not clear whether it can be applied to urban sanitation as

well.

2.1.4 Demand-responsive approach

Demand-oriented policies correspond to what Heierli et al. (2004)

call «the new paradigm»,

in reaction to traditional subsidised programmes. They advocate a

greater involvement

of the private sector to provide better solutions and create

demand, along with a stronger public sector to encourage desirable behaviours

and discourage bad ones. One of the ideas of this new paradigm is to use

marketing as a tool to raise demand and provide more suitable sanitation

options; the so-called «sanitation marketing» is described in the

next section.

|