2.3.2 The strong Porter Hypothesis

Brännlund and Lundgren (2009, p. 9) defined the strong PH

as the productivity gains induced by the ER so that the whole costs of

attaining it are, at least, compensated by the productivity increases. In this

context, it is relevant to point out that Porter (Porter, 1991; Porter and van

der Linde, 1995) has the credit of giving an approach that deviates from the

dominant design in those days. Porter's argument was that: appropriate

government environmental intervention can trigger innovations that can offset

the costs of compliance with the regulations. As a result of strict ER,

companies will reconsider their production process and will develop new

approaches to reduce the pollution while lowering their costs and / or

increasing their production. The possibility that regulation encourages

innovation imply that firms decisions are not always the optimal choices as

there is a high level of information imperfection and a certain inertia while

organisational opportunities and technologies are developed continuously. Thus

many innovation opportunities are overlooked by firms as their level of

awareness is limited. If ER stimulus to eco-innovation is sufficiently

important then ER would offer the possibility to improve environmental

conditions at zero cost or negative net costs by improving productivity.

Consequently, by stimulating innovation, ER may actually make businesses more

competitive. As an example, regulations on recycling products could lead to the

recovery of valuable materials more easily. Both consumers and producer could

then end up winners when disposing of the consumed product. (Lanoie &

TANGUAY, 1999)

Undoubtedly, such a view has received close attention from all

stakeholders who want stronger environmental policies, such as

environmentalists. If ER may be without costs or even with negative costs then

regulation is good for both the environment and the businesses.

Porter initially expressed his argument in a one-page article

(Porter 1991) and then extensively formulated it in a common article with van

der Linde (1995) and later on with Esty (1998). According to Porter (1991)

«strict environmental regulations do not inevitably

hinder competitive advantage against foreign rivals (p.

96)». And «... the environment-competitiveness debate has been framed

incorrectly (Porter & van der Linde 1995, p. 97)». The authors

emphasised the crucial role of innovations as their core argument. Wagner

(2004) indicated that: «In reality, one is faced with a dynamic

competition process, rather than a framework of static optimization.»

Because firms are «... currently in a transitional phase of industrial

history where companies are still inexperienced in dealing creatively with

environmental issues (Porter & van der Linde 1995, p. 99)», which

implies incomplete information and organisational inertia. Wagner (2004) adds:

«In such a situation properly designed regulation can have an influence on

the direction of innovation in that (Porter & van der Linde 1995, p.

99-100):

- It signals to firms resource inefficiencies and possibilities

for technological improvement;

- If focused on information provision, it can increase firms'

awareness for improvement potentials;

- It reduces the uncertainty of net paybacks from investments;

- It «... motivates innovation and progress» (Porter

& van der Linde 1995, p. 100);

- It provides a `level playing field' and is necessary in

situations with incomplete offsets.»

The idea underlying the reasoning of Porter is that pollution is

generally associated with resources and raw materials that are not fully

utilised or wasted energy.

«Pollution is the emission or discharge of a (harmful)

substance or energy form into the environment. Fundamentally, it is a

manifestation of economic waste and involves unnecessary, inefficient or

incomplete utilization of resources, or resources not used to generate their

highest value. In many cases, emissions are a sign of inefficiency and force a

firm to perform nonvalue-creating activities ... Innovation offsets will be

common because reducing pollution is often coincident with improving the

productivity with which resources are used.» (Porter and van der Linde,

1995, p. 98)

Thus there is room for innovation in order to prevent

pollution and reduce the waste. Specifically, Porter refers to two broad

categories of innovations. Firstly, process improvements when reducing

pollution is associated with higher productivity through material savings,

reduced energy needs and reduce costs of disposal; a typical example is to find

ways to use waste, scrap and residues as new combustion source. Secondly, there

are also gains to be made at products level where reducing pollution is

accompanied by a design

product of higher quality, safer, cheaper, with more value for

the consumer or is less costly to the trash. (Lanoie & TANGUAY, 1999)

The academic research conducted by Sinclair-Desgagné

and Gabel (Sinclair-Desgagné 1999; Gabel & Sinclair-Desgagné

2001; 1993) came to a similar conclusion, they considered in fact ER as

«... an industrial policy instrument aimed at increasing the

competitiveness of firms, the underlying rationale for this statement being

that well- designed environmental regulation could force firms to seek

innovations that would turn out to be both privately and socially profitable

(Sinclair-Desgagné 1999, p. 2)». Moreover they proposed a number of

conclusions such as «... [it is] inconsistent, albeit convenient, to

assume that markets are flawed but that firms are perfect (Gabel &

Sinclair-Desgangé 2001, p. 149)». Another conclusion was that

although «standard neoclassical-economics models do not support the

systematic presence of low-hanging fruits (Sinclair-Desgagné 1999, p.

3)» the authors indicated that «[I]nnovation itself is not free, and

if one prices managerial time and all other in puts correctly at their

opportunity costs, it should become clear that putting stronger environmental

requirements on polluting firms generally increases their production cost more

than their revenue (Sinclair-Desgagné 1999, p. 2)». Ambec and Barla

(2006) observed that the management tend to be `present-biased' and may delay

investment in costly assets even if they may be productive («low-hanging

fruits»):

«Because the cost of innovating is for «now»

while the benefit is «later,» a present-biased manager will tend to

postpone any investments in innovation. By making those investments more

profitable or requiring them, environmental regulations help the manager

overcome this self-control problem, which enhances firm profits» (Ambec,

et al., 2010).

In addition, according Gabel & Sinclair-Desgangé

(2001) «[It] is logically most likely in situations where the firm is far

from the efficiency frontier, where the burden of the compliance cost is light,

and where the shift to the frontier can be made cheaply» (p. 152).

Finally, Xepapadeas & de Zeeuw (1999) concluded that «basic argument

nevertheless remains the X-efficiency argument that external shocks caused by

stringent environmental regulations may reduce inefficiencies and failure

within the firm».

Another way to look at the situation is to suppose that

businesses might operate under their potential because of bad management and

lack of perfect information. A clear definition of property rights (Coase,

1960) with regulation to limit information asymmetries (Akerlof, 1970), may

lead to Porter's the win-win or positive sum game with Pareto

improvement. In practice, however, regulation usually has been

associated with decreased competitiveness, deterring innovative activities

(Cerin, 2006).

Ambec and Barla (2007) explain, through a game theory

application, the spill-over effect of R&D investment that justifies the

Porter hypothesis. Consider two firms with the same technology and each with a

monopoly on two separate markets. They get a profit of ðp. Each

firm must decide whether to invest in research and development (R&D) to

achieve a more productive and cleaner technology that allows it to achieve a

gross profit of ðV with ðV >ðp. The cost

of developing this new technology is I. Consider the extreme case where the

spill-over is complete so that a company has a perfect access to results of

another firm at no cost. In other words, innovation is a public good. A company

can have access to new technology at no cost if its competitor invests in the

project. If the two companies perform R & D investment that each should

I/2. The game is represented by the following matrix:

Spill-over effect of innovation

Firm 2 No R&D R&D

Firm 1 NoR&D

R&D

ðp, ðp

|

ðv, ðv -I

|

|

ðv -I , ðv

|

ðv -I/2, ðv -I/2

|

Figure1: Ambec and Barla (2007)

So if ðv-I <ðp but

ðv-I/ 2> ðp, then this is exactly the

situation of the so-called classic `prisoner's dilemma': the Nash equilibrium

is `no firm invests' while if they could cooperate, both would benefit from the

jointly developed the new green technology. Environmental regulation as a

standard that forces the adoption of new technology could therefore benefit

both players. Other environmental regulations a priori costly for the company

such that a carbon tax or a system of emission permits would lead to the Nash

equilibrium where both firms invest in R&D. They save on the costs of

R&D spill-over, the new technology requires an investment of individual

I/2. Their final gain is ðv-I/2, greater than the gain before

regulatory Nash equilibrium ðp. (Ambec & Barla, 2007)

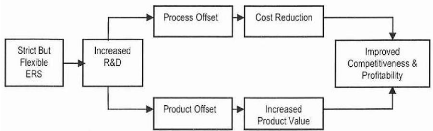

Schematic representation of the Porter hypothesis

Figure2: Ambec & Barla, (2006)

|