|

Running head: The Private Equity Asset Class

The Private Equity Asset Class

Investment Rationale, Valuation Exercise & Modern

Financial Techniques

Wilmington University

Student: Hedi Chaabouni

MBA Finance

Instructor: Mr. John J. Bish

February, 22, 2008

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments Page 3 / 102

Introduction Page 4 / 102

Part I- The Rationale behind Private Equity financing

Page 8 / 102

Chapter 1: PE Asset Class Page 10 / 102

Chapter 2: PE Value Chain Page 17 / 102

Chapter 3: PE Strategic Power Page 31 / 102

Part II- Private Equity and Valuation Page

42 / 102

Chapter 7: PE Value Chain & Valuation Page 44 / 102

Chapter 8: PE & Value Based Management Page 47 / 102

Part III- Modern Financial Techniques & Private

Equity Page 55 / 102

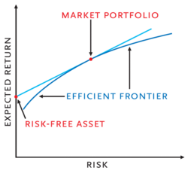

Chapter 9: Portfolio Theory in PE Page 57 / 102

Chapter 10: Risk Management & Financial Engineering in PE

Page 62 / 102

Chapter 11: International Financial Management in PE Page 67 /

102

Conclusion Page 74 / 102

Appendixes: Cases in Emerging Markets

Appendix 1: Emerging Market Definition & Risk Profile Page

75 / 102

Appendix 2: DCF Valuation in Emerging Markets, the SPAM model

Page 78 / 102

Appendix 2: A Case Study in Emerging Markets Page 92 / 102

References Page 102 / 102

Acknowledgments

I would like first to thank my finance instructors at Wilmington

University who devoted time to teach me the concepts I need to become a well

enlightened finance student. I especially thank Mr. John J. Bish for having

taught me what the price of everything is; with his insight he gave me the keys

to the secrets of finance.

I especially thank Mr. Aziz Mebarek, cofounder and managing

partner at Tuninvest, a Private Equity firm with whom I made my first steps in

the field in 1997 as a member of the board of a family business this investment

firm invested in. With his unique insight, he inspired me and insufflated in me

the passion for the Private Equity industry. He also gave me some feedback

about his emerging market experience that helped me bridge the gap between

theory and practice when writing this thesis.

Finally, a part of my acknowledgments goes to Mr. Majdi

Chaabouni, a family member, today a top executive at a leading Arab bank in the

Middle East. He is the one behind my dynamic of finance studies and English

language graduate education. He taught me to go beyond my limits and passed me

the passion of writing.

Introduction

In this recent time where Private Equity funds are thriving

globally and becoming a very serious alternative and sometimes a

«trendy» way to raise money and finance industrial

operations and business acquisitions, I thought that a contribution to an open

debate in a somewhat close financial industry would be an interesting and

healthy endeavor for the educational and business communities. Indeed, many

formal books already exist on Private Equity; they describe the investment

process from A to Z and the different types of transactions that could take

place in terms of timing, type and size of the company invested in.

Yet, my interest in the industry made me wander in spaces I never

intended to visit. This year, when performing my MBA Finance, I first started

working on some papers related to Private Equity and found that each paper was

somewhat related one to the other. From this fact stemmed the idea of a thesis

encompassing several related articles describing and outlining the hot topics

today debated around Private Equity.

The first draft of this thesis was therefore entirely dedicated

to explore what issues matter today in the industry, and what is the rationale

behind PE investments. Its purpose was then to answer questions about PE

specific hybrid nature, the reasons behind its phenomenal returns and the

breakdown of its value chain, and how this type of investment has gained an

indisputable power amid other financing tools.

But after a while and this thesis continuing germinating in my

mind, I found these issues to be just a starting point and decided to push the

reflection further and try to explore new fields in the industry by broadening

the traditional scope of discussion about Private Equity. I had my part one for

this thesis but what about the rest?

As the valuation concept and techniques are at the core of the

Private Equity process I decided, with the advise of my finance instructor, to

devote the whole second part to it. After all, neither value chain, nor

strategic power, exists without a sound valuation process and techniques.

Valuation being an important part of my finance curriculum, this academic

thesis aiming also to encompass all the concepts I touched on in my MBA

program, it was natural to describe and analyze this concept from the

beginning.

As and when I kept touching on new subjects and topics in the

finance courses I'm actually taking, many other questions arose in my mind

about the structure of Private Equity. Issues like modern portfolio theory or

risk management and the use of derivatives within PE funds fully retained my

attention. What if a PE fund applies some of the principles of portfolio theory

a mutual fund uses? And what if a PE fund starts using derivatives to hedge a

stake acquired in a privately held business? Obviously, in Private Equity

today, these are not conventional practices. Nevertheless, many unconventional

practices in the past time became conventional today after researchers and

practitioners gained footings in spaces formerly recognized insurmountable.

Here came the idea of the last part of this thesis which I call the prospective

technical part. Its purpose is dual: first to start a reflection on the

practice by the PE industry of modern financial techniques today widely used in

financial markets, and second to dig in some technical aspects Private Equity

is nowadays exposed to as international investing.

Finally, an appendix part is devoted to study a specific and

today topic in economy and finance, the emerging markets. The choice to tackle

the emerging market issue is probably dictated by my belonging to a country and

region classified as so. In this part, the emerging market definition and risk

profile are reviewed, and a Discounted Cash Flow Analysis valuation technique

specifically applied to emerging markets is highlighted and deeply explained.

View differently; this PE thesis is tackled through four

different and complementary angles. First, the rationale driving the industry

is deterred to reveal the reasons behind the value creation engine in PE;

second a closer look is given to valuation and how its process and techniques

impact PE process; third modern financial techniques are cited to explore new

and unconventional scopes in PE daily management, and finally the merging

market issue in economy and finance is highlighted. The objective of this

thesis is hence to make readers better grasp the Private Equity industry

practice and challenges and in the same get acquaintanced with a today hot

topic on the global business place: the emerging markets.

Part I: The Rationale behind Private Equity

financing

Why more and more investors allocate money to PE funds rather

than traditional vehicles or securities like mutual funds and stocks? Is PE

less risky than Mutual Funds? Of course not. So why this behavior? What makes

wealthy individuals and big institutions accept to wait 10 to 12 years before

receiving any of their returns? Why they accept to give a proxy to managerial

teams to minister their funds and in the same time are keen to forgive almost

all their monitoring power over these funds? The answer could only be that the

investment is worth the waiting time, the lost of power and the risk taken. Ok.

So how this asset type works? What makes it different from other

types of assets? And how PE creates this value today so much sought-after? What

is underlying its value chain? Is there a house secret inside PE that makes it

so appealing? Why PE firms and funds almost always outperform traditional

groups and corporate holdings also involved in acquisitions and disposals of

units, subsidiaries and other affiliates?

The purpose of this first part is to answer clearly and concisely

all these questions that might come to you when dealing with the PE industry.

Chapter 1 will explain what type of asset class is PE and how investors look at

it against other financial assets. Chapter 2 will give an insight on the value

chain sequence in PE and how value is created and cashed in through the entire

investment process. Chapter 3 will delve into more strategic insight by trying

to enlighten the reader on the strategic secrets of PE and what makes it

outperforming traditional business management in terms of returns and value

creation.

Chapter 1: What type of asset class is PE?

Definition:

What is Private Equity? «Any equity investment in a company

which is not quoted on a stock exchange». Although everyone agrees on this

basic definition, it is no more an exact one since an increasing convergence

between the activities of private equity funds, hedge funds and property funds.

Hence, let's get clearer about what is exactly Private Equity.

The most fundamental distinction in the PE industry is between

those who invest in funds and those who then manage the capital invested in

those funds b making investments in companies. This distinction is also defined

by the terms «Fund Investing» and «Direct Investing».

Terminology:

Those who invest in funds are called «LP's», since the

most common form of PE fund is a Limited Partnership; the passive investors are

called Limited Partners. Whereas direct investment where money gets channeled

into investee companies is the role of the PE manager called «GP» for

General Partner.

The investment process may therefore be seen as two levels: the

fund level and the company level, and this distinction is the difference

between «fund investment» and «direct investment». In fact,

each level requires its own particular modeling and analysis, and each also

requires its skills.

Structure:

But how these PE funds work? Usually, a limited partnership is

known as a close end fund since it has a finite lifetime typically between 10

and 12 years. This always has been the case in USA and UK but les the case in

other regions. In Europe for example, much private equity investing took place

through open-ended structures. These called «evergreen» vehicles were

the subject of lot of criticism from the Anglo-Saxon observers who claimed that

they provided little incentive to managers to force exits from their

investments and that their returns could not validly be compared with LP's

because typically there was no mechanism for them to return capital to

investors.

Cash Flow:

PE funds are unlike ay other form of investment in that they

represent a stream of unpredictable cashflows over the life of the fund, both

inward and outward. These CF are unpredictable not only as to their amount but

also as to their timing.

When a fund needs cash, either for the payment of fees or the

making of investments, the GP will issue a «drawdown notice»

sometimes called Capital Call. This will ask for a certain amount of money to

be paid into a specified bank account by a certain date and will give brief

details of what the money is required for.

The LP will then check that the purposes for which the money is

required are valid according to the terms of the LPA (Limited Partnership

Agreement) and that the amount has bee correctly calculated. It will then take

steps to execute the «drawdown notice» by making the required bank

transfer.

Distributions are the other side of the cash flow. Whenever a

fund exits an investment by sale or IPO, then they will have to cash available

to return to investors. This is usually done by a «distribution

notice» which is just the opposite of a «drawdown notice», and

will notify each individual investor of how much money they may expect to have

transferred into their bank account, and when. Since the timing of exits is

unpredictable the so necessarily is the timing of distributions. And to inject

further uncertainty into the situation, a fund may actually sell its stake in a

company in tranches over time.

Investment:

The most important thing to understand about the way in which a

PE fund invests is that investment power is in the manager or GP hands. The LP

have no voice at all in the investment process and, indeed, should not want to

have since there is a significant risk of them losing their limited liability

if they can be shown to have played an active part in the management of the

fund.

The combination of passive investing and long fund lifetimes has

made private equity a risky asset for some and has emphasized the need for

extreme care and specialist skills in the selection of managers in the first

place.

Fundraising:

Most PE funds tend to work to a 3-year fund cycle which means

that in the third year of Fund I they will be out fundraising for Fund II, and

so on.

The first step in the fundraising process should be for the PE

team to sit down and plan their investment model for their next fund. This

should consist of mapping out where the most lucrative returns are likely to be

made, assessing how many of these investments they can secure, and thus how

many are likely to be made in a 3-year period and how much money is required

for them. They will then choose to raise exactly that amount of money plus a

small contingency and no more.

The next stage in the process is to prepare an Offering

Memorandum (sometimes called a Private Placement Memorandum) which is the legal

document on the basis of which investment will take place, although the actual

contractual document is of course the LPA, which will be signed separately by

each investor, or made the subject of a subscription agreement, which will be

signed separately by each investor.

What happens next is usually that the decision process is

preceded or followed by a period of due diligences, during which the LP's team

will carry out as much analysis and checks on the GP's. In practice, it is

probably more accurate to say that in most cases the decision process will be

accompanied by the due diligence process, since some analysis may well be done

at a very early stage; on the historical financial performance for example;

while the final decision may well be expressly subject to due diligence which

has yet to be carried out.

The final stage in the process sees the lawyers intervening as

the terms of the LPA are debated and negotiated. In reality, such is the

bargaining strength of the GP's in desirable funds that little of any substance

is usually conceded to LP's.

Returns:

How Returns are measured in PE and why? How may we compare them

with the returns of other asset classes? These are several questions that this

section will try to address.

First, what lies at the heart of how Private Equity works is the

concept of the «J-curve». And this is exactly what makes PE so

different from the other asset classes. Indeed, «Annual Returns»

cannot be used as a guide to PE performance, whereas for most people this is

the only return that matters for every other asset class.

We already said that unlike any other asset classes, an

investment in a PE fund represents an investment in a stream of cash flows. Of

course there are other assets which would appear to satisfy this definition

like bonds, but a huge difference remains between the two assets. Because a

bond has typically one cash outflow and then a series of cash inflows with the

exact dates and amounts, we can calculate at any time the yield of as bond.

In a PE fund, we will rather have a series of cash outflows as

money is being drawn down from the LP's, but both the timing and the amount of

these outflows is totally uncertain. In the same way, there will be a series of

cash inflows as the GP distributes the proceeds of investments as they are

realized, but again its is completely impossible to predict in advance how much

each one of these will amount to, or when it will occur. In fact, the

calculation of a return in the case of a PE fund can only be made once the very

last cash flow has occurred. More than that, usually the biggest inflows tend

to occur at the end of the fund's life rather than in the beginning.

Hence, we need to look at the compound return over time which is

the IRR of a PE fund in order to assess its performance. And it is there when

we meet the famous «J-curve» phenomenon. In fact, the J-curve is

produced y looking at the cumulative return of a fund to each year of its life.

The first entry represents the IRR of the fund for the first year of its life;

the second entry represents the IRR for the first two years, and so on. In this

way, any PE fund will show strong negative returns in the early years as money

is drawn down. However, as distributions start to flow back to the investor

then the downward shape of the IRR curve will be reversed and there will come a

year when the amount of inflows will precisely match the amount of outflows,

creating an IRR of zero. This is the point when the J-curve crosses back over

the horizontal axis and subsequent IRR's start to become positive and upward

sloping. It is this difficulty of being able to abandon the annual returns view

and look from the perspective of compound returns that makes the PE industry so

different and perhaps so compelling amid the entire financial industry.

Thus, PE returns are calculated and stated not as the annual

returns of any year, but as compound returns from a certain year which is the

year of creation of the fund to a specified year. When looking at benchmark

figures in the industry as a whole or as any part of it, the all the funds

which form part of the sample that were formed in the same year are grouped

together and their returns become what we call the «Vintage year

return». In fact, the «vintage year» will always show the

compound return of all funds formed during the vintage year, from the vintage

year to the date specified. If we also look at the J-curve, we realize that at

any time, the vintage year returns for the last few years meaning the most

recent should be very low or even negative because they represent the

equivalent of the first few years of the J-curve, at a time when even the best

PE funds will show negative returns. And subsequently, the greater the number

of years over which a vintage year compound return is calculated, the more

robust it becomes, the less deviation there is likely to be between it and the

final fund return. It is indeed meaningless to look at the performance of a PE

fund in the early years; generally these are the first five years.

Now that we clearly defined the asset class and explained how it

works and how its returns are viewed and computed, let's turn to the next

chapter and see how the PE asset class creates value for its investors and what

is the exact process of value creation for a PE fund. In other terms, let's

try to mirror and understand from a sequenced process perspective, the J-curve

and the compound returns of a PE fund we just touched on in this chapter.

Chapter 2: PE Value Chain

Private Equity funds are institutional and privately owned

investment vehicles managed by highly skilled and multidisciplinary teams that

invest equity and quasi equity, for a limited period of time, in growing

businesses, usually unlisted, with potentially high returns. Since these funds

make the major part of their profits when the owned stake in a firm is sold

out, the «portfolio firm valuation» is the central piece for

assessing the total return on investment.

Capturing indeed a «firm value» is the beacon

and the final aim of every Private Equity management team. Yet, what

«value» are we discussing here? There are in fact two

different values: the value paid to buy the firm stake and the one received

when this stake is sold out. Both values are paramount to Private Equity funds.

Yet, to better understand the meaning of these values, let's

first breakdown the investment process in a specific «value chain

sequence» that will help the reader go through the dynamics of

«value creation» in Private Equity.

Six stages could be laid out to describe this process even if on

a practical hand each of these stages could be broken down in turn in more sub

stages, but we're not going to go through this detailed process since it's not

the main topic of this paper. The six subsequent stages are:

1- Selection: Firm prospects are

selected to form a book of potential valuable investments.

2- Pre Valuation: From the selected

prospects, few would go through a complete «valuation

process» since this will determine which companies would «strike

a deal».

3- Due Diligences: Once the selected

prospects are pre-valued, the choice is narrowed down again and the final

selection would go through a complete audit (technical, financial and

legal).

4- Closing: After the results of the

audit, one or more companies will receive both the fund team agreement to enter

in the fund portfolio for a determined period of time.

5- Portfolio Management: These

portfolio firms will be actively managed by the inside managerial teams with

the full support of the fund team to reach the operational and financial

objectives set at the closing stage.

6- Post Valuation: When a portfolio

firm has reached the objectives and goals set at the closing stage, generally

after 5 years of operations, the fund team starts looking again at the new

value of the firm in order to prepare the selling of the company. A new

valuation is then undertaken by the fund analysts' team.

7- Exit: After a period of time,

generally 5 years, the portfolio firm stake initially invested will be sold out

to a strategic or a financial buyer, the fund then makes its return on

investment and creates value for its shareholders.

Naturally, all the stages participate in their way to create

value and generate returns for the investments undertaken:

Ø The «Selection» stage allows the

funds to wisely select its prospects through an adequate fundamental and

environment analysis.

Ø The «Pre Valuation» stage through a

specific «financial analysis» precisely values the retained target

companies.

Ø The «Due diligences» stage allows

through a thorough audit of the technical/operational, financial and legal

aspects of the company to alleviate the investment risk and target only healthy

firms.

Ø The «Closing» stage is a check point

that allows the funds to form a potentially valuable portfolio.

Ø The «Portfolio management» stage

enables the firms already in the fund portfolio to reach the goals and

objectives set and agreed at the «closing» stage.

Ø The «Post Valuation» also values

trough a specific «financial analysis» the portfolio companies that

will very soon exit the fund perimeter.

Ø The «Exit» stage is another check

point that allows the funds to realize and «cash in» its

returns.

Our main purpose in this paper is to distinguish through the

different stages of the Private Equity «value chain

sequence» what are the stages that contribute to the

«intrinsic value creation» compared to the stages

that don't but rather create value through «investigation and

negotiation dynamics».

Hence, we came up to a simple classification here laid down in

the next diagram. The «Selection», «Pre

Valuation», «Post Valuation», and

«Portfolio Management» stages are part of the

«intrinsic valuation» process in the sense that they all

contribute to the inception, determination and build up of the

«intrinsic value».

Whereas the mechanisms driving the «Due

diligences», «Closing» and

«Exit» involving both «technical and operational

expertise» and «corporate legal and financial engineering tools»

that are beyond the scope of this paper, are stages that help, throughout the

«investigation and negotiation process», transform

the «intrinsic value» in a «real» or

«strike value» that is the value agreed upon whether at the

investment or at the divestment phase.

Here after is laid down a graphic that summarizes and synthesizes

the concepts of the value chain process and its sequence as we explained in

this chapter.

Negotiation or Strike Value

Intrinsic Value

Investigative Value

Economic Value

Check Points Value

Private Equity Value Chain Breakdown

Selection

Due Diligences

Potential Valuable Portfolio

Pre Valuation

Closing

Portfolio

Management

Portfolio Value Maximized

Post Valuation

Exit

Fund Returns Maximized

The following will be a dig in the different stages that make up

the intrinsic value of the firm, which we consider the main parameter that fund

managers should look at when dealing with an investment in a company and also

when looking at the fund as a whole.

We absolutely don't say here that the other stages laid down in

the PE value chain process are not important or less important, each stage has

its own importance that is equally weighted compared to the other, because if

it is no the case, there will no «chain» process, as we know in a

chain each ring is equal with all the rest. These stages have also a clear

impact on the «intrinsic value», whether it is the «due

diligences», the «closing» or the «exit» stage because

they can or increase or decrease the «intrinsic value» with the

results and outcomes of the «investigation and negotiation dynamics».

Our purpose in the following sections is indeed to point out how this

«intrinsic value» is located and monitored through the value chain

process to enable a PE fund to collect the maximum amount of intrinsic value in

its portfolio thus creating the maximum wealth for its shareholders.

The «Selection» stage:

Let's now delve into our first stage and try to

answer how Private Equity fund teams should select their prospects. From a

«security» perspective, the proper price for a firm stock is

based on a forecast of the future dividends and earnings that can be expected

from the firm. This master part of the valuation process is called the

«fundamental analysis».

Yet, because the prospects of the firm are tied to those of the

broader economy, «fundamental analysis» must also consider

the «business environment» in which the firm operates.

Hence, «macroeconomic» and «industry»

circumstances must be examined in order to assess the environment in which the

firm involves. Briefly outlined, the «environment analysis»

includes (Bodie, Kane, Marcus, 2007):

A- Macroeconomic Analysis

· The Global Economy

· The Domestic Macro economy

· Demand and Supply Analysis

· Government Policy: Fiscal, Monetary and Supply-Side

policies

· Business Cycles and Economic Indicators

B- Industry Analysis

· Definition of the Industry

· Sensitivity to the Business cycle

· Sector Rotation

· Industry Lifecycles

· Industry Structure and Performance

Traditionally, the «security analyst» works

out this analysis throughout the «valuation process» so that

investors are well informed about the future expected returns of the stock in

consideration. In Private Equity, the «investors» are the

fund shareholders that gave a proxy to the fund management team to administer

and manage the fund in order to reap the maximum returns allowed under the

specific circumstances. Hence, fund managers should consider their private

targets as «securities» or «stocks» to be

analyzed prior to any investment decision. In this case, «fundamental

analysis» remains the most rigorous and most reliable process to

analyze an investment prospect.

Indeed, «environment analysis» due

to its rigorous and orderly approach would help financial analysts in Private

Equity funds apply a «market methodology» to private and

closely held firms that:

- Will mitigate investment risks by deeply looking into all the

financials and economics that drive a firm future value.

- Will pave the way for extracting a higher value in the

future.

Yet, the exercise could seem more complex when a firm involves in

an «emerging market» (see annex for a detailed definition of

«emerging market») environment where economies are less efficient,

less transparent and more volatile than in the «developed

markets». This «asymmetry» problem in itself is

sufficient to emphasize the enforcement of an aggressive «environment

analysis» using all the means and tools at hand (national reports and

studies, international organizations data centers and reports, central banks

notes and reports...).

The fact here is that due to this high volatility,

«environment analysis» should be emphasized as for a

«traded security» in order to allow mitigates the

incremental risks associated with the expected higher returns. But because

financial and economic data are often hard to define due to the lack of

transparent and exact available information, the market driven methodology

would spur the managers and analysts involving in these «emerging

markets» deals to keep more than an eye on the importance of

«environment analysis» which in turn would stimulate more

efforts and research to look at and determine what stands in and behind the

economic and industrial drivers for the firm and the sector targeted.

To conclude on this part, through an adequate screening of the

sectors, their industry drivers and macroeconomic factors, we came up to

qualify this «selection process» as the inception stage of

«intrinsic value» for a private equity portfolio. Indeed, a

wary and wise choice for future investments is the start point for

«value creation» in private equity funds. The following

parts dealing with the next stages will say more about how «intrinsic

value» is build up.

The «Pre Valuation» & «Post

Valuation» stages:

In this part, our analysis will only focus on both

«valuation». In other terms, the

«valuation» stages will answer these two questions:

a. How these funds value businesses to find bargains for their

future investments (Pre Valuation)?

b. And how they value again these investments when comes the time

to sell them out (Post Valuation)?

The answer is that these funds should look every time to the

«intrinsic value» or «technical value» of

the firms before deciding on whether or not they should invest in the firms

prospected and selected and also after having invested and managed the

portfolio firms. It is only by looking at the «intrinsic

value» of the firms before and after investments that the funds would

maximize its opportunities to realize the required returns by its shareholders.

At the «Pre Valuation» stage, after having

selected some potential targets probably involving in different business

segments and different environments, the main challenge of the fund team is to

decide from its prospects the right «bargains» to

«strike» for. Another challenge awaits the fund team after

having invested some potentially interesting companies and managed them

throughout the portfolio for a limited period of time; it is the «Post

Valuation» stage. At both stages, the funds analysts' teams work out

the «intrinsic value» of the firms under scrutiny. From the

latter analysis, some potential interesting firms start to show up in different

environments and different sectors.

Now, the challenge of the fund team is to select from its

prospects the right bargains to strike for. The analysts' team starts then

figuring the «intrinsic value» of the firms targeted; this

is what we called earlier the «valuation» stage. Many

valuation techniques and models exist (e.g. DCF, Multiples & Comparables,

Real Options) when the exercise is to value companies and each situation

requires a specific set of tools; a framework describing each situation and

what method to employ for valuation purpose exists in the financial literature;

but the «fundamental discounted cash flows» (DCF) is by far

the most used by the professionals and the one that best fit the valuation of

closely held companies targeted by Private Equity funds.

The «Portfolio Management» Stage:

Getting into the last part of this paper, everyone agrees that

the fundamental goal of a firm's financial management is to maximize

shareholders wealth. This obviously applies to Private Equity funds, where as

we said earlier, the ultimate goal of the fund management team is to create the

maximum value for its shareholders.

But how shareholders wealth and value are created in a business?

The answer is that when a firm makes an investment that will return more than

the investment costs in today`s value. Said differently, a firm is constantly

expanding its operations through capital investments to finance new projects

and the underlying new assets. These new capital assets make the production

capacity of the firm. These investments will also determine how efficiently the

firm will operate and how profitable it will be in the future.

In real life, as a firm has more than one project in its

«project portfolio», its management is always confronted

with a crucial choice: what projects should be undertaken now and what projects

should be delayed? As these projects are typically expensive, their

implementation will determine the competitive position and the long term

survival of the firm in the marketplace. Hence, no one can doubt that deciding

on what, when and how it costs to implement a specific project could be

absolutely critical for a firm future health. Facing this decision, the firm

management should therefore be at the same time prudent and wise without losing

insight on the opportunity costs if a project is not undertaken. In another

words, these decisions are highly challenging.

That's when financial «capital budgeting»

should become the «science» for the managers faced with

these challenges. Indeed, several methodologies are at hand when dealing with

capital budgeting, although we can safely state that the «Net Present

Value» (NPV) discounted cash flow (DCF) model is the most achieved

technique in modern finance. The NPV of a capital expenditure in a specific

project is the present value of all cash inflows, including those at the end of

the project's life, minus the present value of cash outflows. The NPV rule is

to accept a project if NPV > 0 and to reject it if NPV < 0 (Eun and

Resnick, 2007).

Additional methods exist (IRR, Payback, Profitability Index...)

for analyzing capital investments and each of them can provide pieces of

information for decision making, but the NPV is considered to be superior when

dealing with capital budgeting decisions.

Turning back to our firm management faced with this decision

making process, we can safely assume that if a firm «projects

portfolio» is prioritized according to the NPV rule that is the first

project that will be undertaken is always the one with the higher NPV, the firm

management is taking the right and wise decisions regarding its expansion

aiming to maximize the shareholders value. Said differently, if a firm

undertakes its capital investments according to the NPV rule, it means that it

has prioritized its expansion stages and «disciplined» its

«growth» in order to achieve the highest shareholders

wealth.

Let's just translate all this methodology to Private Equity

funds. If the fund management team is actively involving in the management of

its portfolio firms with a unique goal that is maximizing its shareholders

value, then the fund managers should accompany and support the whole portfolio

firms' management to adopt this «disciplined growth» by

obeying to the NPV rule. The aggregate result would be a maximization of the

fund portfolio value.

A diagram presenting the portfolio «intrinsic

value» maximization mix in a Private Equity fund is laid down in the

next page.

Maximization of the Fund Total

Intrinsic Value

Portfolio Intrinsic Value Maximization Mix in

Private Equity

1st: Prospects Selection

via Environmental Analysis

3rd: Portfolio Management

through Capital Budgeting & Disciplined Growth

2nd: Firm

Pre Valuation using DCF

![]()

Chapter 3: The Strategic Power of Private Equity

To address the issue of what drives the strategic power of PE

funds and understand what is behind the phenomenal returns of the major PE

funds, albeit the early negative returns we touched on when we explained the

J-curve phenomenon in Chapter 1, I tried to take ground on two articles

recently released on the September 2007 «Harvard Business Review».

These articles are totally independent one from the other, yet I kept asking

myself whether the first could feed the latter and reciprocally and found out

after thought that these two articles combined will form an excellent source of

knowledge for our current issue.

Indeed, the first article named «The Strategic Secret of

Private Equity» is dealing with the strategies Private Equity firms deploy

to achieve high returns on investments, the latter named «Rules to Acquire

By» depicts a methodology to abide by for groups of companies and

corporations seeking to expand and grow using external acquisitions. Obviously,

the basic common ground between these two articles is the fact that both

Private Equity funds and Corporate groups are engaged in a permanent process of

external acquisitions. Yet, their in-house alchemy differs and so are their

returns and successes.

Through the analysis of both cited articles, I will attempt in

this chapter to give an insight about the «strategic power» of

Private Equity funds by comparing them to common corporations and private

groups. The fact is that usually, corporate groups are also constantly

involving in acquisitions processes. So by comparing the respective practice of

PE funds and Corporate groups when dealing with acquisitions, we will give an

insight on what drives the dynamics of both toward success or failure, and try

to find out if one category could learn from the other.

In the first cited article, Felix Barber and Michael Goold, both

directors at the «Ashridge Strategic Management Centre» in London,

attempt to give a strategic insight on the powerful «Secret» Private

Equity firms use and in some cases probably abuse to dramatically increase the

value of their investments.

The question is why Private Equity firms achieve high growth and

correlated high returns in the businesses they acquire whereas Corporate groups

barely digest their acquisitions and wait a long term before experiencing

acceptable returns?

Many well known reasons could answer this question (Barber and

Goold, 2007):

- Both Private Equity firms' Managers and Portfolio Businesses

Operating Managers receive high incentives,

- An aggressive use of leverage and debt which provide both

financing and tax advantages,

- A clear focus on cash flows and margins improvements,

- A freedom from restrictive public companies regulations being

private and often closely held entities.

But the fundamental reason behind Private Equity skyrocketing

growth and returns is something else. The driver for such encountered successes

is more mechanical and less financial than usual practitioners could observe.

Indeed, Private Equity industry thrived in the mid-way between «pure

financial investment firms» and «pure operational management

businesses». This pivotal position to refer to a mechanical term

makes the major reason for Private Equity blurring success. Let's just think

about this a few moments. Is there another type of investor that holds this

strategic position amid the financial and business community? In my opinion,

the answer is obviously negative.

The authors qualify this phenomenon as Private Equity funds

«standard practice of buying businesses and then, after steering them

through a transition of rapid performance improvement, selling them. That

strategy, which embodies a combination of business and investment-portfolio

management, is at the core of Private Equity's success». The Venn diagram

here after presented, reveals the «Hybrid Nature» of Private Equity

firms.

Investment Portfolio Management Firms

Operational Management Businesses

![]()

Private Equity Firms

However, this «Buy-to-Sell» strategy could not be fully

implemented by Corporate groups that acquire businesses with the intention to

integrate them into their core operations creating synergies for a long term

run. In the meanwhile, and as Private Equity track records show, the

«Buy-to-Sell» strategy is perfectly matching when the purpose of the

investment is to make a one-shot, short to medium term value creation.

For that, buyers must take the ownership and control of a target

company, often one that hasn't been aggressively managed and so is currently

underperforming or an undervalued business with potentials not yet apparent. In

such cases, after the changes necessary to achieve transformations and drive up

the firm value have been implemented (usually around 5 years), it makes sense

for the buyer to sell out the business and turn over to new opportunities

following the same line fashion.

In fact, records also show that Corporate groups, usually public

companies, still holding to their acquisitions even after value creation

changes and transformations occurred, are somewhat diluting the terminal value

and final return of their investments by forgiving to sell out businesses at

the apex of their value.

Both practices are indeed justified by the different ways Private

Equity funds and Corporate groups work and also by the manner their respective

shareholders perceive their buying activities.

First, PE funds are obligated by their shareholders to sell out

the portfolio businesses and liquidate the entire assets of a fund within its

lifetime; therefore acquired businesses remain under pressure to perform.

Whereas as Corporate groups shareholders expect long term synergies (sometimes

in vain!) and operational integration that will sustain the total shareholders

value in the future, the businesses belonging to their portfolios don't get

immediate attention from top management whether they are well or under

performing and thus reflexes to immediately restructure, sell out or take on

other strategic actions are not triggered in a timely manner as do Private

Equity funds, always on the hot spot.

This in turn leads to another reason for the insolent performance

of the Private Equity industry. Because, Private Equity structure requires a

rapid turnover of businesses due to the limited life of the funds, the result

is that PE funds gain strong and fast knowledge of buying, transforming and

selling businesses that few Corporate groups develop. Perhaps the nature of

Private Equity top managers has also something to do with that, whereas Private

Equity partners as former investment bankers are keener to trade, most

Corporate groups top mangers have operational and line background and are so

more comfortable to manage that to buy and sell.

Now, after having discussed all these differences, the question

is what should Corporate groups do and change to narrow down if not overcome

the outperforming Private Equity industry?

The authors give a tangible answer by proposing two distinct

strategies:

1- Adopt the same Buy-to-Sell framework

2- Take on a Flexible Ownership strategy

Rapidly explained, the first point could be implemented by

overcoming a corporate culture of a «Buy-to-Keep» strategy embedded

in the nature of Corporate groups. It also requires that a Corporate group

develop new resources or shift them, hire new skills and change some of its

structures to adopt Private Equity oriented approach. This strategy should also

be explained to shareholders which beliefs can be qualified as somewhat

traditional; in that case, both the board and the top management need to argue

the new approach of the Corporate group portfolio of businesses. This can be

easily expressed but highly challenging to implement and achieve.

In contrary, the «Flexible Ownership» means that a

Corporate group could hold on acquired businesses as long as these can add

significant value by improving their performance and continuing their growth,

and then can dispose of them once it is no longer the case. In fact, if a

Corporate group decides to hold on to an acquired business, it can give it a

competitive advantage over Private Equity funds which must sometimes forgo

substantial over returns they could realize if they would keep on the

investment for a longer period of time. «Flexible Ownership» is

likely to lure most industrial and services holdings with fewer synergies

between subsidiaries, Corporate groups could keep businesses with potential

long term core synergies or transform and sell units with no longer more

synergies yet with a sustainable go-alone strategy. Following the

«Flexible Ownership», Corporate groups should also be wary about

keeping businesses after corporate top management could no longer contribute to

create more value. In a sense, the latter comment embodies the

«gauge» that indicates when and whether a business should be kept,

transformed or sold.

Taking ground on all what we explained here up, let's now find

out what the second article provides as insight for the present discussion.

This article deals with the outstanding success of Pitney Bowes, a US company

that experienced 70 external acquisitions in six years!!

Pitney Bowes is a US multinational firm specialized in providing

mail stream solutions that allow companies to improve and integrate all the

activities essential for business communication, the company operates in 130

countries with a current turnover of $5.7 billion.

The author, Bruce Nolop, an Executive Vice President and CFO of

the company, is arguing that success or failure from an external acquisition

process is due to the mere fact that some companies have figured out how to do

it right, and other don't.

The problematic laid out here is the fact that much recent

studies revealed that the «impulse to buy other businesses is a sign of

weakness, that corporate cultures don't mix, and the majority of acquisitions

simply fail». Yet, on the flip side, the records show that world's most

successful companies rely heavily on acquisitions to achieve their strategic

set of goals and objectives.

So the question is: who is right? As a part of an answer to this

question, Bruce Nolop tried to bring up and share the experience of his company

in the subject, through a fairly set of basic rules that could apply to most

companies.

Here are his key guidelines:

- Rule 1; Stick to Adjacent Spaces:

This approach means pursuing development on logical extensions of

a company's current business mix, which can be taken on incrementally.

- Rule 2; Bet on Portfolio Performance:

This rule emphasizes the fact to manage acquisitions as a

portfolio of investments introducing diversification and all the technical

rules applied to asset management in terms of risk analysis, liquidity and

expected returns.

- Rule 3; Get a Business Sponsor Involved:

Acquisitions processes should be sponsored by inside business

leaders who establish and maintain strong working relationships with the new

management teams to smooth their entry into the buyer culture and operating

procedures.

- Rule 4; Be Clear on How the Acquisition Should be

Judged: Distinguish between acquisitions that will perfectly fit

into a business or a market the buyer is already in, and acquisitions that

takes the buyer into a new business space or activity. Both types should be

treated and appraised differently, the second is naturally more difficult and

entails more risks that the first.

- Rule 5; Don't Shop When You Are Hungry:

On a strategic level, «Hungry» means that the business

is missing an element that the management feels it urgently needs. However,

this does not have to translate into impulsive acquisition.

In fact, whether or not this set of rules perfectly matches other

companies, the main lesson applies to all businesses: acquisitions should be

managed as a «process». As all business processes, this one should be

documented, practiced, improved and mastered. Said differently, it means laying

down the «complex chain of actions typically involved in an acquisition,

paying attention to what can go right or wrong at different stages,

standardizing effective approaches and tools, and continually improving these

approaches». «This aims to create more smart and efficient buyers,

discipline the unit managers about which companies should get into an

acquisition pipeline, and help keep away from apparent tempting deals that turn

out to be in fact disappointing. This also ensures that the acquisitions

completed would finally make more strategic, business and financial

sense».

Does this process-oriented acquisition strategy developed by

Pitney Bowes Company and here laid out answers to the previous question about

how could Corporate groups compete in the area with Private Equity firms? I'm

pretty much sure that readers will find out on their own.

In fact, although the majority of already known cases highlight a

segmentation of strategies for the Private Equity funds and the Corporate

groups, each one could learn from the other by adopting the outsider line of

work if and when the case appeals so.

Private Equity could hence benefit from a «Buy-to-Hold»

strategy for portfolio firms that still show high growth and more value

creation in a longer term (more than 5 or 6 years) to end up with a much high

profitable sell out of the business.

Corporate groups could in turn reap profits from a

«Buy-to-Sell» strategy and sell out or spin-off businesses that have

reached successful transformations in a limited time fashion, avoiding in the

same time to consider such «divestments» as «strategic

errors».

Part II - Private Equity & Valuation

Before unveiling what our chapters are about, I couldn't find

more interesting words than those of Luis E. Pereiro to introduce the toughness

of the issue in his preface of «Valuation of Companies in Emerging

Markets» (Wiley, 2001):

«Valuation is the point at which theoretical finance hits

the harsh road of reality. You may be one of the many managers, advisors, or

researchers faced with appraising the economic value of a new investment

project, a merger, an acquisition, or a corporate divestment. You may have

attended formal finance courses; you may even hold an MBA or an MFA; and still

you are puzzled and frustrated when you attempt to implement the elegant

theories of corporate finance in real life valuation exercise. This is hardly

surprising, for financial theory and practice have formed an easy partnership

that often ends in dissolution. On one side, of this partnership are the

academics, who have their sophisticated risk-return models; on the other side

the practitioners, who stand by their expertise in crafting real-life

acquisition deals. The professional appraiser sits uneasily between the two

groups, often being squeezed uncomfortably by both. All the while, the crucial

problem - how to sensibly and plausibly value a real asset- remains at best

only partially solved.»

After reading these words, I guess the tone is set up for what

will follow. How the PE industry deals with the valuation of companies is a

tremendous issue. In this part, we will not be able to dig into the details of

the valuation techniques but rather point out how the industry tackles that.

Hence, the first chapter will give an insight about how PE funds

deal with the valuation of companies across their «value chain»;

whether at the pre acquisition or at the post acquisition stage (chapter 2). It

will also point out what are the practices of PE funds regarding valuation as a

daily management issue.

The second chapter will rather emphasize the notion of

«Corporate Value creation» and the so called «Value Based

Management», and stresses the standpoint of PE funds toward these notions

and concepts.

Chapter 4: Private Equity Value Chain &

Valuation

Before delving into the core of this chapter, we need to quickly

explain where PE funds conduct their business, in other words, what are the

domains where PE funds thrive.

PE funds as we said earlier are hybrid vehicles sitting between

classical corporations and asset management investment funds. This is also the

case from the standpoint of their acquisitions. Indeed, PE funds have two

targets of firms:

1- Closely held companies, non publicly traded stocks

2- Publicly held and traded companies

A simplistic definition would say that usually the PE funds

involving in the acquisition of the first type of companies are called

«Venture Funds» and «Generalist Funds»; whereas those

involving in the second type of companies are called «Buyout

Funds».

Venture & Generalist Funds have a clear exposure to early and

growth stage companies thus almost always invest in closely held corporations;

whereas Buyout Funds have more exposure on traded stocks in the way that they

structure their deals to extract the publicly held company from the stock

market and make it go private with the Buyout Fund as the main shareholder.

This being presented, we can assume that these two types of PE

funds have different practical approaches to how to appraise their targets but

remain convergent regarding the financial techniques and models used for that.

Hence, we will not present in this chapter their differences but rather the

common ground in valuation between them.

Usually, in developed countries and markets, the valuation of

public or closely held companies is a precise endeavor: the classical models of

corporate finance must be considered and adapted when dealing with real-life

valuations. In the US, considered the most efficient financial market, the use

of well established frameworks such as the CAPM, the arbitrage pricing theory

(APT), or the real options, poses serious challenges to the practitioner. No

agreement exists among academics and practitioners concerning many crucially

important issues, issues as basic as deciding on the market risk premium to be

used, whether an option is truly embedded in a real asset, or how precise the

multiple method is compared to DCF analysis. This demonstrates how perilous is

the appraisal exercise for professionals dealing with real assets, which is our

case for the PE industry.

Now, for the PE funds, and according to the «Value

Chain» we described in chapter 2, we can safely confirm that the most

important valuation exercise concerns the «Pre Acquisition» stage,

what we called «Pre Valuation». Obviously, before taking the last

decision to put money in a company, the fund should be profoundly aware about

the exact value of this company. Since the investment will be carried out for a

period of about five years, the «Pre Valuation» will be the

masterpiece of the transaction process. We need to keep in mind to understand

this, that the PE fund doesn't know well the company at the Pre Acquisition

stage, sometimes neither its specific products, nor its top management. The

issue evolves differently at the Post Acquisition stage, when the PE fund had

the time to better know the firm, its core business and its management style.

Obviously, the Post Acquisition will also require a new valuation

of the portfolio company after a number of years in the fund portfolio, but

this will be a «light» version of the «Pre Valuation»

mission. So rather than the «Pre Valuation» which involves a precise

and thorough deployment of the «Valuation Process», the «Post

Acquisition» will be more or less a monitoring of the value appraised at

the Pre acquisition stage.

Now that the differences between the Pre and Post Valuation

highlighted, let's set a framework for this «Valuation Process». The

one that will be presented here after is more suited for the Venture &n

Generalist Funds and their closely held early and growth stage companies than

for the public companies targeted by Buyout Funds. Although, the differences

are sometimes thin, we preferred to focus more on the closely held companies

case and the inherent practices of the Venture and Generalist PE funds, and

less on the Buyout Funds practices that target public listed companies since

there is plenty literature for valuation of public stocks here in the US and

also because this thesis is more about private equity in the sense of privately

held companies by opposition to publicly held companies.

Chapter 5: Private Equity & Value Based

Investing

Is there a room for «Value-Based Investing» in the PE

industry? To answer this question, let's first rapidly define the concept.

The notion was first introduced by Columbia Professor Benjamin

Graham in his classic «Security Analysis» text where he developed a

method of identifying undervalued stocks, meaning stocks whose prices were less

than their intrinsic value. This became a cornerstone of modern value

investing. Also, Graham approach was to focus on the value of assets such as

cash, net working capital, and physical assets.

But this approach has since evolved under the philosophy of

investor super guru Warren Buffet. Indeed, Buffet modified that approach to

focus also on valuable assets such as franchises and other intangible assets

that were unrecognized by the market at that time. Here are the principal

elements of Buffet investment philosophy:

1- Economic reality, not accounting reality: Financial

statements prepared by accountants conformed to rules that might not adequately

represent the economic reality of a business.

2- The cost of the lost opportunity: Buffet compared an

investment opportunity against the next best alternative, or the marginal best

alternative in more economic words; that is the «lost opportunity».

3- In value creation, time is money: Buffet assessed

intrinsic value as the present value of the future expected performance and

that book value is meaningless as an indicator of intrinsic value.

4- Measure performance by gain in intrinsic value, not

accounting profit: The gain in intrinsic value could be modeled as the

value added by a business above and beyond the charge for the use of capital in

that business. It is a measure that focuses on the ability to earn returns in

excess of the cost of capital.

5- Risk and discount rates: Discount rates used in

determining intrinsic values should be determined by the risk of the cash flows

being valued. The more the risk, the higher the discount rate. The conventional

model for estimating discount rates was the CAPM, which added a risk premium to

the long term risk-fee rate of return. Buffet developed a philosophy against

Beta in computing the cost of capital by arguing the fundamental principle:

«it is better to be approximately right than precisely wrong».

6- Diversification: Buffet disagreed with conventional

wisdom that should hold a broad portfolio of stocks in order to shed company

specific risk.

7- Investing behavior: Buffet believes that investment

behavior should be driven by information, analysis, and self-discipline, not by

emotion, fashion or «hunch».

8- Alignment of agents and owners: Buffet believes that

to do the best investment, one should think that he is investing his own money.

Now that «Value-based investing» as Graham and Buffet

conceived it, do PE funds believe in it? Apply it? And is it applicable to PE

transactions.

My answer is yes. In my opinion, the majority of Venture, General

and Buyout PE funds follow the philosophy of value based investing. And I do

believe that PE among other asset classes is the one that embodies at best the

lessons we had from Graham and Buffet.

If I go along the eight points developed by Buffet and listed

here above, I would confirm that yes PE funds are good in «value-based

investing» at an exception of one criterion: the use of time as a valuable

asset in «value-based investing». Indeed, because of the timeline

defined in the LPA's, PE mangers are almost obligated to return all the

proceeds from divestments in a time fashion that do not exceed 10 years. This

make them often forgo a valuable part of the excess returns a portfolio company

is making but selling under time strain. Their strategic power of

«buy-to-sell» as we explained in chapter 3, is good at making

phenomenal returns, but also bad at making the «maximum returns» an

investment can bring.

The concept of value based investing was first developed to

address the investment behavior in the US stock market by institutional,

private, and mutual funds investors. Yet, there is something that strikes me if

I go back to my private industry and small business experience. All the

principles here up exposed and developed by Buffet also perfectly apply to

small businesses, in the way that they are common sense of wise and aware

entrepreneurship. So if the concept applies to publicly traded stocks, closely

held companies like those in PE funds portfolio, and also to small businesses

as I mentioned here, does this signify that the concept is transversal and

universal? I believe yes. Even if a valuation exercise applies to the most

sophisticated investment opportunity in Wall Street, I really believe that a

valuation process based on «value-based investing philosophy» is a

common sense of how to do business wisely and not following emotions or

fashions. In that sense, valuing GE or a Delaware based small business follow

the same principles, even if the proportion of data to collect and the tasks to

undertake hugely differ in terms of volume; in that case it is more a matter of

scale than of valuation philosophy.

Back to PE, Robert F. Brunner, a Distinguished Professor at

Darden Business School, University of Virginia, presents a case study in his

book «Case Studies in Finance - Managing for Corporate Value

Creation» (Mc Graw Hill, 2007) that deals with a growth stage Private

Equity investment. The reflection process held by Louis Elson, Managing Partner

at Palamon Capital Partners, a generalist UK based PE fund, when dealing with

the acquisition of TeamSystem S.p.A., an Italian based accounting and payroll

software company, perfectly matches what we described as the «Value-based

investing» philosophy. Here are some extracts illustrating our opinions.

Palamon Investment Process:

Palamon's investment process began with the development of an

investment thesis that would typically involve a market undergoing significant

change, which might be driven by deregulation, trade liberalization, new

technology, demographic shifts, and so on. Within the chosen market Palamon

looked for attractive investment opportunities, using investment banks,

industry resources, and personal contacts.

About TeamSystem S.p.A.:

TeamSystem was founded in 1979 in Pesaro, Italy. Since its

founding, the company had grown to become one of Italy's leading providers of

accounting, tax, and payroll management software of small-to-medium-size

enterprises (SME's). Led by a cofounder and CEO Giovanni Ranocchi, TeamSystem

had built up a customer base of 28,000 firms, representing a 14% share of the

Italian market.

Palamon's search generated the opportunity to invest in

TeamSystem S.p.A. In early 1999, before Palamon's fund had been closed, Elson

had concluded that the payroll servicing industry in Italy could provide a good

investment opportunity because of the industry's extreme fragmentation and

constantly changing regulations. History had shown that governments in Italy

adjusted their policies as often as four times a year. For Palamon, the space

represented a ripe opportunity to invest in a company that would capitalize on

the need of small companies to respond to this legislative volatility.

Industry Profile:

The Italian accounting, tax, and payroll management and software

industry in which TeamSystem operated was highly fragmented. More than 30

software providers vied for the business of 200,000 SME's with the largest

having 15% share of the market; TeamSystem ranked number two with its 14%

share. All of the significant players in the industry were family-owned

companies that did not have access to international capital markets.

Analysts predict that two things would characterize the future of

the industry: consolidation and growth. Consolidation would occur because few

of the smaller companies would be able to keep up with the research and

development demands of a changing industry. As for growth, experts predicted 9%

percent annual growth over the period 1999-2002. That growth would come

primarily from increased personal computer penetration among SME's, greater

end-user sophistication, and continued computerization of administrative

functions.

The Transaction:

After TeamSystem pas performance and the sate of the industry,

Elson returned his attention to the specifics of the TeamSystem investment. The

most recent proposal had offered EUR25.9 million for 51% of the common shares

in a multipart structure that also included a recapitalization to put debt on

the balance sheet.

Valuation:

To properly evaluate the deal, Elson had to develop a view about

the value of TeamSystem. He faced some challenges in that task, however. First,

TeamSystem had no strategic plan or future forecast of profitability. Elson

only had four years of historical information. If Elson, were to do a proper

valuation, he would need to estimate the future cash flows that TeamSystem

would generate given market trends and the value that Palamon could add.

His best guess was that TeamSystem could grow at 15% per year for

the next few years, a pace above the expected market growth o 9%, followed by a

6% growth in perpetuity. He also thought that Palamon's professionals could

help the CEO improve operating margins slightly. Lastly, Elson believed that a

14% discount rate would appropriately capture the risk of the cash flows. That

rate reflected three software companies' trading on the Milan stock exchange,

whose betas averaged 1.44 and unlevered beats averaged 1.00.

The second challenge Elson faced was the lack of comparable

valuations in the Italian market. Because most competitors were family-owned,

there was very little market transparency. The nearest matches he could find

were other European and U.S. enterprise resource planning (ERP) companies and

accounting software companies. Looking through the data, Elson noticed the high

growth expectations (greater than 20%) for the software firms and

correspondingly high valuation multiples.

Risks:

Elson was concerned about more than just the valuation, however.

He wanted to evaluate carefully the risks associated with deal,

specifically:

- TeamSystem management team might not be able to make the change

to a more professionally run company. The investment in TeamSystem was a bet on

a small private company that Elson hoped would become a dominant, larger

player. Its CEO had successfully navigated the last five years of growth, but

had, by his own admission, created a management group that relied on him for

almost every decision. From conversations ad interviews, Elson concluded that

the CEO could take the company forward, but he had concerns about the ability

of the supporting team to deliver in a period of continued growth.

- TeamSystem was facing an inspection by the Italian tax

authorities. The inspection posed a financial risk and therefore could serve as

a significant distraction for management.

- The company might not be bale to keep up with technological

change. While the company had begun to adapt to technological changes such as

new programming languages, it still had some products on older platforms that

would require significant reprogramming. In addition, the Internet posed an

immediate threat if Team System's competitors adapted to it more quickly than

TeamSystem itself.

Finally, Elson wanted to make sure that he could capture the

value that TeamSystem might e able to create in the next few years. Exit

options were, therefore, also an important consideration

Part III - Applying modern financial techniques in

Private Equity

This last part is the one I describe as the «most

technical» part. Indeed, the three themes I want to introduce here are all

very important because these are the cornerstones of modern financial theory,

yet they are also very technical and sometimes they imply many mathematical

concepts that are somehow difficult to grasp or to dig in, as it is the case

for the financial risk management discipline.

My goal here is not to unveil details about these techniques,

this is nor my level of knowledge, neither my purpose. My goal for this thesis

is to understand how PE funds deal with these financial techniques when they

are confronted to such issues, and for sure they are. I also want to give to

the reader an insight about the different practices PE funds use when it comes

to face such financial issues in their daily managerial duties.

Divided in three chapters, this part starts by explaining the

stand of PE funds toward financial risk management. Then, it will move to a

more contemporary issue by giving some thoughts about where modern portfolio

theory lays out when dealing with asset management funds in the Private Equity

class. Lastly, we will touch on how PE funds structure their business and deal

with their issues when it comes to play internationally; in other terms, do

they follow and abide by the concepts of international finance or do they have

their own practices in the international marketplace?

Also, I want to add that all this part is basically stemming from

my own experience along head the PE industry in Tunisia, North Africa, where I

spent more than 8 years working besides the PE industry and also inside. So all

the analyses and conclusions in these three chapters are my own thoughts and

insights about the stands of the industry toward these financial disciplines.

Hence, my view could not be exactly the one that a US student will have, but

I'm almost sure that the differences would be quite thin since the PE practices

all over the world tend to be the same and imposed by a sort of a common body

of knowledge and practice.

Chapter 6: Risk Management in Private Equity

Since I started this graduate finance program, my view was

turned to the Private Equity as a financial theme so that I get all the finance

disciplines I learned applied to it. I was sure from an academic point of view,

that this will help me grasp the different concepts I was taught by thinking

how the PE industry will behave in such or other discipline. I finally created

my own case study on a rolling basis. And when came the latter course of

Derivatives and financial risk management, I immediately asked my self this

question: how do PE funds deal with this issue when facing different kind of

risks?

Let me first lay out immediately one concept that will be helpful

for the rest of the discussion. We already explained in part I and II that PE

funds manage portfolios of privately held companies. Hence, there is an

immediate question to ask when the financial risk management discipline: do PE

funds manage risk on a fund level, which I call «direct level» or do

they manage risk on a portfolio company level, which I call «indirect

level»; or do they manage risk either way meaning on a «direct»

and «indirect» level?

The Indirect Level:

On a portfolio company level, it is obvious for me that the

executives of the company are managing risk when they are facing it. Maybe the

level of sophistication in risk management depend on the size, the business and

the market where the company is, but we can be safe in saying that every good

management will try to minimize the risks associated with the global operations

of the company if the financial market where the company is supposed to act in

does allow the execution of risk management transactions such as derivatives

instruments.

The Direct Level:

Now on a direct level, the question is more interesting. Do PE

funds manage risk associated with their portfolios of companies on a

consolidated level? In my opinion, no, I really never heard or remarked a PE

fund managing risk on a global portfolio basis, yet this might exist, I simply

saying here that I don't believe this is a common practice.

So, my sub consequent questions are why they don't do so and

should they?

Well, I do think that PE funds executives as asset managers have

an eye on the risks associated with holding those assets for a predetermined

period of time. But I do think also that due to the fact that the portfolio

companies are not public companies, they have already avoided » the market

risk associated with the stock price, and then they narrowed down the risks to

a non market one, or as it is called to an «unsystematic» risk

compared to the «systematic» market risk.

Now that they have only «unsystematic» risks to manage,

how can we break down these risks so that we can have a more in-depth insight

into the question. I'll breakdown the unsystematic risks faced by the PE

portfolio companies into four categories of risks: Forex risk, Commodity risk,

Interest rates risk, and Credit risk.

As we said earlier, on a «direct level», a wise

management will surely undertake to manage these four risks by:

- For the Forex, Commodities and Interest Rate risks: entering