4.2.3. Controversial topics mentioned:

The results of the exploration of the coursebook, reported in

Appendix H, shows that there are six controversial topics mentioned, which are

alcoholic beverages, out of marriage relationships and revealing clothes,

dealing with some dangers in particular countries, religion, and celebrating

specific ideological icons.

As to alcohol, it is one of the PARSNIPs that Gray (2002)

mentioned as being avoided in ELT coursebooks and yet it is mentioned using 11

referring items in H/I. Throughout the coursebook, the word alcohol or a

related idea can be found (see table 5 below). As summarised in Table 5,

alcohol or related terms and situations are mentioned in ten out of the twelve

units.

Table 5: Referring items related to spiritual beverages

in each unit of the coursebook

|

Referring items

|

Units

|

|

Image of alcoholic beverage

|

1

|

|

Coffee bar

|

2

|

|

drinking, alcohol, bars

|

3

|

|

Alcohol, beer, image, champagne, wine

|

4

|

|

Going for a dink, bar,

|

5

|

|

(No references)

|

6

|

|

(No references)

|

7

|

|

Beer, champagne

|

8

|

|

Lager, pub

|

9

|

|

beer

|

10

|

|

drinking

|

11

|

|

A drink, pub, champagne

|

12

|

Needless to say that in many instances these terms were

repeated more than one time in the same unit such is the case of «a

drink» mentioned in pages 94, 95, 96, and 132. Another example of the

insensitivity with which coursebook writers treated the topic of alcohol when

writing this global coursebook is manifested when they designed a situation in

which two children are thinking of offering their father a lager on his

birthday.

Alcohol is banned in some civil laws and in religious writings

of some cultures, which makes its inclusion in the content of ELT coursebooks

«inappropriate» for many societies. However, for Hill (2005), the

avoidance of PARSNIP's is considered unethical, as one could not imagine an ELT

coursebook without mention of alcohol especially for reasons related to

socialisation and cross-cultural understanding. This means that alcoholic

beverages are part of target language culture and mentioning them helps global

users understand the culture and the society of the «native» users of

English.

It could be said that Gray's (2002) claim about global

coursebooks' avoidance of alcohol is not correct at least for H/I as the

analysis revealed references to alcoholic items in 10 out of the 12 units

constituting the whole coursebook. One could, then, come to the conclusion that

what is inappropriate for global users is considered less important, this time,

than «authenticity» of representation of target language culture.

In fact, the mention of spiritual beverages is not

inappropriate for the western world and at the same time could not be avoided,

as it constitutes an important component of the culture of western societies

especially for doing business (Hill, 2005). Therefore, investing in target

culture is «inappropriate» in this case, which shows again the

impracticality of over-relying on global coursebooks and the necessity of

thinking either about appropriation measures or taking the courageous decision

of setting programs for developing local or glocal coursebooks.

In fact, based on the findings of this study, it could be

suggested that locally produced coursebooks do not need to be hyper-local in

the sense of being limited to a very specific region or even country. Local

coursebooks could be designed for blocs sharing similar realities and

perception about what is «appropriate» and what is not, which means

similar cultures. An example could be designing coursebooks for the North

African region. Such a procedure was resorted to by major publishing companies

who designed coursebooks for groups of countries as indicated by Gray

(2002).

This solution, in fact, allows for more localisation of

content. As to the North African region, there appears to be no specific

coursebook designed to meet the needs and expectation of learners from it. A

possible explanation for this is that the market is not sufficiently profitable

to the extent that world publishers design specific coursebooks for it. The

English program coordinator in a private language school in Tunisia informed

the researcher (October, 2009) that the consultant of Oxford University Press

has recommended H/I for Tunisian and Libyan learners despite its weaknesses

documented in this study. Compromises should be considered at the local or

regional levels rather than at the global level.

The problem, then, concerns compromising, that is deciding

what to avoid and what not. Such compromises that writers and publishers of

H/I, as well as other coursebook writers (Bell and Gower, 1998; Hill, 2005),

were obliged to make, show how fuzzy global coursebooks are and how hindering

they are for «authentic» and at the same time «appropriate»

content. It seems that there are really very few themes on which all humans

agree, which could then be «appropriately» and

«authentically» used in ELT coursebooks. Spiritual beverages would

not be a problem if the coursebook was designed only for learners belonging to

societies accepting them.

For learners from cultures considering the inclusion of

alcohol in the content of the coursebook as inappropriate, they could have been

replaced by coffee or tea, as they are acceptable components of some local

cultures unless the lesson is about cultural habits. This problem is what drove

some societies to design their own coursebooks like Iran (Alikbari, 2004).

Localising the content of ELT coursebooks could be a viable solution in order

to profit from the qualities of coursebooks published by world publishers while

at the same time guaranteeing the possibility of their being used in diverse

contexts without possible problems of rejection and resistance on the part of

learners or institutions.

Additionally, revealing clothes (shown in 8 out of 12 units)

and out of marriage relationships like dating (unit 1) and cohabitation (units

2, 3, 6, 9, and 11) are normally socially unacceptable for Muslims, which makes

mentioning them in coursebooks «inappropriate» (see Appendix H). A

similar conclusion was arrived at by Ellis (1990) who stated that some

«inappropriate» topics like dating may not be accepted by some

cultures and yet they are used in ELT practices. Despite their problematic

status, out of marriage relationships are present in the global coursebook

Headway Intermediate (Soars and Soars, 2003). Such a denial of the

sensitivity of similar issues may give credit to interpretations relating the

inclusion of these topics to the idea of cultural imperialism (Phillipson,

1992) and generally conspiracy theories or at least cultural insensitivity to

problematic issues. It is worth noting that learning may not occur if learners

do not trust the coursebook they use (Canagarajah, 1999), which raises

questions about the reasons behind including them in a coursebook that is

assumed to be global.

Depicting a particular country as dangerous could be also

considered «inappropriate» and yet it was mentioned by the writers of

H/I. They reserved two pages (unit 4) to talk about the dangers in Thailand

representing it as an unwelcoming country to visit. This issue is

controversial as the writers of the coursebook pretend that

their product is global. As mentioned earlier, «globality»

necessitates catering for a global audience and this image of Thailand may

result in Thai learners' rejection of this coursebook.

The exploration of the coursebook revealed also that religion,

which is stated in Gray (2002) as to be avoided by coursebook writers, is dealt

with even if not explicitly. There are in fact some references to Christianity

while at the same time there are no direct references to other religions. If

referring to Judaism could be «inappropriate» for some Muslims and

possibly so is referring to Islam for some Jews, then what makes the publishers

believe that Christianity is acceptable? Learners may develop the idea that

there is an attempt to present it as an agreed upon religion while others are

not.

This could distract their attention from concentrating on

acquiring the language to thinking about hidden ideological content in the

material. It could be said that the world is connected and people need to learn

about each other so that they can communicate and keep «peace» and

understanding, as this is a mission that education can serve. However, talking

about one religion and ignoring others may be interpreted as a hidden

missionary act, which might inhibit learners from trusting and efficiently

using the coursebook and learning effectively in some parts of the world.

This insensitivity could legitimate researchers' claims that

English is related to missionary activities (Phillipson, 1992), which is not

beneficial for the global use of the global coursebook. This is another problem

of imported global coursebooks. Making successful compromises is, in fact, the

core problem of ELT global coursebooks. Put simply it is impossible to be

global in a diverse world.

The problem of whether it is up to the West to convert towards

the `dos and don'ts' of Muslims or up to Muslims to convert to those of the

West is a controversial issue that could

be related to what is called «clash of

civilisations» (Huntington, 1996). This contention could be avoided by

either trusting and subsidising local ELT coursebooks production or at least by

recommending localised coursebooks from world publishers after providing them

with lists of local topics to be avoided. This «glocalisation» (Gray,

2002, p. 166) operation could neutralise learners' and teachers' resistance and

rejection of global ELT coursebooks on the basis of their ideology-loaded

content.

Ideological icons are one of the issues to be avoided or at

least treated with equity (if equality is ever possible in ideology

representation) in ELT coursebooks to evade audiences' rejection (Gray, 2002).

However, in H/I ideology is not totally avoided as the analysis revealed subtle

instances of ideological bias.

In fact, the content analysis documented instances of

celebrating specific ideological icons that are mainly related to the West with

its values and lifestyle(s). Examples of this ideological bias include arguing

for replacing the wonders of the world (unit 1) with

technological advances, mentioning Armstrong (without any

reference to the Russian YuriGagarin, for instance), mentioning

Madonna (unit 11), Uncle Sam (unit 11), Frank Sinatra

(unit 12), Hemingway and Picasso (Unit 3) without any

reference to icons from periphery countries. Apart from a very brief mention of

Nelson Mandela (unit 1), there were no other «Third World»

celebrities, which could give credit to the claim that the coursebook is

embodying and serving a particular ideology, which is that of the capitalist

consumerist bloc (Phillipson, 1992; Canagarajah, 1999; Riches, 1999;

Rinvolucri, 1999).

Being a language teaching resource, the global coursebook

communicates many ideas to learners directly and/or indirectly, which makes

preserving balance in coursebooks an urgent need and a challenge. It could be

argued, then, that the language of H/I is western and so is the culture to be

incorporated. In fact, some authors argue that it is not a must to teach

target language culture in order to learn a foreign language

and an example for this is that stated by Kubota (2002) who talked about the

decision on the part of Japanese authorities to invest their own culture in ELT

to avoid cultural imperialism. The idea of target culture teaching could, in

fact, be seen as a form of serving particular ideological interests using

global ELT coursebooks as these latter represent «textual emanation of the

discourses of the institutions of a target culture» (Burgess, 1993, p.

315).

Through the content analysis it was possible to demonstrate

that the writers of H/I showed only partial concern for avoiding

«inappropriate» global issues. In fact, the state of

«globality» may be unattainable, given the huge and contradicting

amount of controversies that the writers need to consider. The global

coursebook seems to fail at the level of world cultural diversity, as little

consideration is given for the sensitivity of some topics and behaviours in

some cultures. These caveats deprive H/I of its «globality».

Such a conclusion shows again the fuzziness of the notion of

the global coursebook and provides arguments for localisation of ELT

coursebooks or at least glocalisation (Tomlinson, 2001; Gray, 2002), which is a

term referring to blending «local and international partners»

(Bolitho, 2003) in order to «bring the best of both worlds to the writing

process» (ibid). This means mixing cultural components derived from the

global and the local in the design of the content of ELT coursebooks.

The contextualisation (Nunan, 1991; Howard & Major, 2004,

p. 105), humanisation (Tomlinson, 2001), and degeneralisation (Hill, 2005) of

coursebooks could mitigate Wajnryb's (1996) claims that global coursebooks

present the world as «safe, clean, harmonious, benevolent, undisturned

(sic) and PG-rated» (qtd in Tomlinson, 2001). This helps designing a

coursebook that is as nearer as possible to learners' realities and specific

daily lives for better and effective learning.

It seems that finding a compromise between being sensitive to

world cultures on the one hand and promoting cross-cultural knowledge through

ELT coursebooks on the other hand is not and could not be successfully

accomplished relying on the global coursebook H/I, which could legitimate

«de-generalisation» (Hill, 2005) of global coursebooks. This means

designing specific coursebooks for specific cultures, which narrows the

conditions manifested in the general guidelines imposed on coursebook writers

and the compromises they find themselves obliged to make. Just like publicity

is localised in global media (Gray, 2002), global coursebooks could too be

localised not only to evade learners' resistance of content (Canagarajah, 1999)

but also for the learners to find their voices (Kramsch, 1993) in the content

as manifested in their representation.

In the following section, the practicality of the principle of

connectedness will be explored in H/I.

4.3. The global coursebook and global

connectedness

Connectedness could encompass several components but for

practical reasons it was studied in this study with reference to three

features; leisure activities, the issue of language, and global connectivity.

The choice of these possible features was based on the researcher's perception

and expectation of what could connect global audiences.

4.3.1. Leisure activities

97 different leisure activities were mentioned in H/I. Table 6

summarises them and provides the frequency of their mention in each unit.

Table 6: Leisure activities and their frequency in each

unit of the coursebook

|

Leisure activities

|

Number of times

|

|

Unit 1

|

Travel

|

5

|

|

Sport

|

2

|

|

Holiday

|

1

|

|

Internet

|

1

|

|

TV

|

2

|

|

Party

|

2

|

|

Unit 2

|

Sport

|

8

|

|

Music

|

1

|

|

Party

|

1

|

|

TV

|

2

|

|

Unit 3

|

Music

|

1

|

|

Film

|

3

|

|

Travel

|

3

|

|

Holiday

|

1

|

|

Sunbathing

|

1

|

|

Sport

|

2

|

|

Play

|

1

|

|

Unit 4

|

Travel

|

2

|

|

Unit 5

|

Travel

|

11

|

|

Sport

|

7

|

|

Dancing

|

1

|

|

Unit 6

|

Dancing

|

1

|

|

Music

|

1

|

|

Sport

|

1

|

|

Travel

|

1

|

|

Unit 7

|

Travel

|

6

|

|

Sport

|

2

|

|

Unit 8

|

Travel

|

6

|

|

Film

|

1

|

|

Unit 9

|

Holiday

|

2

|

|

Party

|

1

|

|

Travel

|

4

|

|

Unit 10

|

Holiday

|

1

|

|

Film

|

1

|

|

Collecting dolls + star wars memorabilia

|

1

|

|

Unit 11

|

Travel

|

3

|

|

TV

|

2

|

|

Unit 12

|

Travel

|

2

|

|

Holiday

|

1

|

|

TV

|

1

|

|

Total number of leisure activities: 97

|

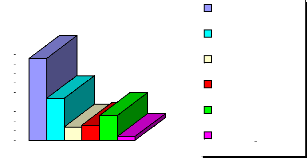

What could be noticed from the investigation of leisure

activities in the coursebook as detailed in Table 6 is that some activities are

mentioned repeatedly, such as travel and sport, while others are less frequent,

like collecting dolls and star wars memorabilia and sunbathing (see Figure 9

below).

Figure 9: Frequency of mention of leisure activities in

the coursebook

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

43

22

7 8

13

2

Frequency

Travel

Sport Holiday/sunbathing

Party/music/ Dancing TV/film/play

collecting

The most mentioned topic among leisure activities is travel

(43 times in 12 units). It seems that for the coursebook writers travel was

considered a «safe topic» (Gray, 2002) that is supposed to be admired

and non-controversial all over the world; presumably, a topic that connects

learners from every part of the world creating a standardised community out of

standardised hobbies.

However, the way in which the writers have dealt with the

theme of travel presents it as if it is easy and affordable for everyone.

Issues related to the problems of obtaining visas and suffering from

segregation in ports are ignored may be as westerners do not face this

problem

when travelling or may be in order to preserve the rule of

«aspirational content» (Gray, 2002, p. 161). The issue of travel,

then, is addressed only from the perspective of the West, which could

legitimate drawing the conclusion that the coursebook is

«ethnocentric», to use Renner's (1997) terminology, in the sense of

marginalizing the concerns of non-western local learners. Possible

«ethnocentricity» in this context is related to writers' concern in

dealing with the issue of travel only from the perspective of westerners not

global audiences.

Sport, in turn, is a theme that is mentioned several times in

H/I, as it is stated 22 times in the 12 units (see Figure 9). Sport is

presented as a global practice, which makes it appear to be safe (Gray, 2002).

However, the in-depth investigation shows that the kinds of sports mentioned

are not available for all learners sufficiently all over the globe. For

example, practicing golf, which is mentioned several times in the content,

might not be possible for many learners even in Tunisia, which might inhibit

the effective interaction of learners.

Certainly, it could be said that learners need to have an idea

about several kinds of sport practiced around the globe. Nevertheless,

following authenticity recommendations (Nunan, 1988; Banville, 2005), investing

locally popular kinds of sport is better than dealing with kinds of sport

rarely practiced by local users of the global coursebook. The point, then, is

that it could be hard for learners to be engaged in talking about a topic with

which they might have no sufficient previous experience. This is again one of

the controversies of designing a coursebook for all the users of English around

the world.

Such a finding could strengthen the idea that global

coursebooks are tailored to meet the needs of westerners and, therefore,

implementing it in non-western countries could be a form of loading it with a

weight that it could not handle for very objective reasons related to the

diverse complexities of diverse learning contexts. Such finding may give

credit, again, to calls for degeneralisation and contextualisation of

coursebooks (Block, 1991; Tomlinson,

2001; Hill, 2005). Dealing with leisure activities that are

mainly related to a particular socioeconomic class could be seen as a kind of

standardisation of hobbies that results from the worldwide penetration of

globalisation. From this perspective, the global coursebook seems to be a

globalisation agent that benefits the politically and economically powerful

bloc, whose elite is thought to be working to preserve the state of the art

favouring the West (Phillipson, 1992).

In addition to travel and sport, Figure 9 shows that other

aspects of leisure activities are used in the content of H/I such as holiday

and sunbathing (7 times), party, music, and dancing (8 times), watching TV,

film, and play (13 times), and collecting (twice). Using these forms of youth

culture could, to a certain extent, provide the coursebook with clients who

want to see the world always bright even if it is not genuinely authentic,

which means not closely linked to learners' local realities. It seems that

there is an attempt to impose a particular vision of the world. A critical

exploration reveals how limited indeed is the horizon that the coursebook

suggests. However, this is done in a subtle way that may not be obvious for

non-critical users and observers.

It seems that using leisure activities as a connectedness

aspect seems to be a cosmetic change that embodies, whether consciously or

unconsciously, ethnocentric orientations, which coincides with critical thought

concerning the existence of the discourse of power in language (Fairclough,

1989) and ELT (Pennycook, 1994; Canagarajah, 1999; Rinvolucri, 1999).

4.3.2. The language issue

It seems that the writers of H/I were very committed to using

what they called Standard English and British everyday English despite the

existence of only two remarks to American

English (Units 3 and 4). There were only two instances of

referring to another slightly different variety, which is American English. The

absence of any other variety from what are called periphery countries

(Pennycook, 1994) in spite of the rising importance of Asian varieties

worldwide (Graddol, 2000) demonstrates a shortfall, or may be choice, of the

writers to cover global varieties and, hence, to be really global at the level

of language.

However, for practical reasons it could be stated that in

order to preserve effective communication, users need to share a unified

phonological code that connects people (Jenkins, 2000). One wonders whether

marginalising global varieties of English is effective or not and, perhaps more

importantly, is acceptable or not especially with the rising importance of

Asian varieties. New Englishes are continuously and persistently gaining ground

especially in Asia (Graddol, 2000), which makes the persistent use of a variety

spoken by a very limited elite a hegemonic act (Phillipson, 1992). Such a

neglect of New Englishes could deprive learners from the opportunity to benefit

from intercultural information that could be provided by using various

varieties, reflecting the real state of English worldwide or even the real

language used in Anglo-American societies (Yule et al., 1992).

Additionally, the rise of English worldwide is expected to be

fashioned mainly by Asians' use of it in business (Graddol, 2000), which means

that the real need of learners practicing business is of Asian varieties, or at

least an idea about them, viewing the economic advance of some Asian economies.

Another rationale for the need of using world Englishes (Kachru, 1985) in ELT

global coursebooks is the avoidance of the charges that global coursebooks

promote stereotypes by presenting the UK and USA language variations as the

most important ones and neglecting other varieties.

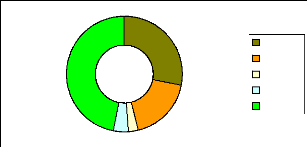

4.3.3. Global connectivity

Global connectivity is explored in terms of the frequency of

mention of countries and continents in H/I. The results of the exploration of

H/I in terms of use of global settings reveal that these settings are

predominantly Western. Figure 10 illustrates this finding and provides the

percentages of mention of other global settings.

Figure 10: Distribution of global settings in the

coursebook

47%

4% 3%

18%

28%

America Asia Africa Australia Europe

In fact, 47% of the locations mentioned in this global

coursebook are European compared to only 3% for Africa, for example. This sharp

difference shows, again, the limitation of H/I to cater for a really global

audience. What is interesting concerning global connectivity is the relative

importance of the mention of Asian countries (18%), which may be to show

awareness of the spread of English across non native contexts. It could be also

a compensation for the numerical and functional misrepresentation of Asians in

the coursebook.

It is worth noting also that 79% of the locations are Western,

as 47% refer to Europe, 28% to America, and 4% to Australia. Such a dominance

of Western locations could legitimate drawing the conclusion that H/I is

ethnocentric as it promotes the dominance of

the West and pays partial consideration to the rest of the globe,

which deprives the global coursebook from being really global.

|