|

KIGALI INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION

OCTOBER 2010

Analysis of factors affecting inflation rate in Rwanda

(1990-2009)

BY: Richard UFITINEMA

REG. NUMBER: 3014/06

A research project submitted to the faculty of social

sciences and business studies, Kigali Institute of education

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

bachelor of social sciences (hons), Economics with Education and QTS

(Secondary).

Word count: 11,080

Supervisor: Mr. Alain Claude KARASIRA

ABSTRACT

This study was carried out in the context of global financial

crisis characterized by a worst inflationary shock in Rwanda during recent

years, it uses chronological data (1990-2009) to analyze the extent to which

changes in Money Supply (M2); in Output (Real GDP); in Exchange rate and

interest rate (Lending rate) influence the inflation. The data consist of the

aggregated data set of 20 years compiled by NBR and NISR. Using a non- linear

and multivariate model, this study estimates the dynamic influence of changes

in M2, in real GDP, in exchange rate and interest rate on Inflation. It is

found that an increase in M2 has a positive and significant influence on

Inflation. Contrary to Real GDP have a negative and significant influence on

Inflation. The study reveals that Money Supply (M2), in Output (Real GDP), in

Exchange rate and interest rate (Lending rate) count for 97.2% variations in

the general prices level (Inflation). Some recommendations are suggested as

emanating from the findings of the study like to pursue a control of monetary

and fiscal policy by government as well as substantial growth in agriculture

sector and other economic activities that contributed in increase of output are

also suggested to moderate the rate of inflation in Rwanda.

DECLARATION

I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to

the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or

written by another person, nor material which to a substantial extent has been

accepted for award of any other degree or diploma at KIE or any other

educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the

project. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have

worked at KIE or elsewhere is explicitly acknowledged in the Report.

I also declare that the intellectual content of this report is

the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in

the project's design and conceptions or in style, presentation and linguistic

expression is acknowledged.

(Signed) ....................................... Date

.....................................

APPROVAL

This is to certify that UFITINEMA Richard has carried out

research entitled «Analysis of factors affecting inflation rate in

Rwanda (1990-2009)» under my supervision and guidance.

Date: ......................................

Signed ...................................

Mr. Alain Claude KARASIRA

DEDICATION

To the Almighty ALLAH,

For your Mercy, Grace and Love,

To my mother, brothers and sisters and my late father who never

lived to see this dissertation,

For your immeasurable love, tolerance, guidance and care, I

respect.

To all who are the dear to me,

I dedicate this memoir.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The success of a dissertation is a big endeavor that one never

claims to own alone and when it comes to expressing gratitude, it is always

hard to find who to thank and who to leave. This is because various people

played different roles under different circumstances in their particular

capacities through out the period of writing my dissertation. However let me

attempt to this great task:

I owe special thanks to my Mum who managed to forego all and

made their son an opportunity cost, without forgetting my brothers and my

sisters who were always there for me during my academic struggle. May God bless

them abundantly.

I extend my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mr. Alain

Claude KARASIRA, I am grateful for their advice, instructions and time

sacrificed towards the success of this work.

I am greatly indebted to my friends for both moral and

academic support.

Lastly I wish to thank the entire staff of the Kigali

Institute of Education; mostly the Faculty of Social Sciences and Business

studies, Department of Economics and Business studies may the almighty God

award you abundantly.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT

II

DECLARATION

III

APPROVAL

IV

DEDICATION

V

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VII

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

IX

LIST OF TABLES & GRAPHS

X

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1

1.1 Background

1

1.2 The research Problem

2

1.3 Research objectives

3

1.4 Research Hypotheses

4

1.5 Significance of Study

4

1.6 Scope of the study

4

1.7 Organization of the study

5

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

6

2.1 DEFINITION OF KEY CONCEPTS

6

2.1.1 Inflation

6

A. Different types of inflation

6

B. Causes of inflation

8

C. Measuring Inflation

9

2.1.2 Consumer Price Index

10

2.1.3 Gross Domestic Product

12

2.1.4 Interest rate

12

2.1.5 Money Supply

13

2.1.5 Exchange rate

13

2.2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

14

2.3 EMPIRICAL FRAMEWORK

17

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

20

3.1 DATA COLLECTION

20

3.1.1 Techniques

20

3.1.2 Types and sources of data

20

3.2 DATA ANALYSIS

21

3.2.1 Methods

21

CHAPTER FOUR: DATA PRESENTATION ANALYSIS AND

INTERPRETATION

24

4.1 DATA PRESENTATIN

24

4.1.1 EVOLUTION OF CPI, M2, Real GDP, ER and

LR (1990-2009)

24

4.2 DATA ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

25

4.2.1 Correlation between variables

25

A. Correlation between Consumer Price Index and Money Supply (M2)

25

B. Correlation between Consumer Price Index and Real Gross

Domestic Product

26

C. Correlation between Consumer Price Index and Exchange rate

27

D. Correlation between Consumer Price Index and Lending rate

28

4.2.2 Regression equation of the model

29

1. Summary of output from SPSS

regression analysis of multivariate

29

2. Specification of general model

30

3. Predictive accuracy of the general

model

30

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

31

BIBLIOGRAPHY

33

APPENDIXES

36

Appendix 1: Regression analysis of consumer price index

and money supply

37

Appendix 2: Regression analysis of consumer price index

and Gross domestic product

38

Appendix 3: Regression analysis of consumer price index

and Exchange Rate

39

Appendix 4: Regression analysis of consumer price index

and Lending Rate

40

Appendix 5: SPSS Result of Regression Analysis

41

Appendix 6: T-Table

42

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CPI : Consumer Price Index

ECB : European Central Bank

ECOSTATS: Economic Statistics

EICV : « Enquêtes Intégrale sur les

Conditions de Vie des Ménages au Rwanda »

FRB : Federal Reserve Board

GDP : Gross Domestic Product

IBR : International Business Research

ILO : International Labor Office

IMF : International Monetary Fund

LOG : Logarithm

NBR : National Bank of Rwanda

NISR : National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda

SPSS : Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

LIST OF TABLES & GRAPHS

TABLES

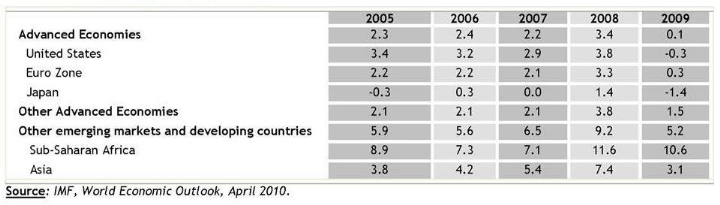

Table 1 : Inflation by region (Annual % change)

Table 2 : Evolution of CPI, M2, Real GDP, Exchange rate and

Lending rate (1990-2009)

GRAPHS

Graph 1 : Trends in Consumer Price Index and Money Supply,

1990-2009

Graph 2 : Trends in Consumer Price Index and Gross Domestic

Product, 1990-2009

Graph 3 : Trends in Consumer Price Index and Exchange rate,

1990-2009

Graph 4 : Trends in Consumer Price Index and Lending rate,

1990-2009

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

Inflation constitutes one of the major economic problems in

emerging market economies that requires monetary authorities to elaborate tools

and policies to prevent high volatility in prices and long periods of

inflation.

Based on the statistics released by International Monetary

Fund (IMF), in industrialized countries, inflation has generally been

controlled. Inflation, measured by the change in the Consumer Prices Index

(CPI), declined steadily, reaching 1.5% in 1998, the lowest rate recorded since

1990, after 2.1% in 1997, 2.7% in 1996 and 2.6% in 1995 (IMF, 1999:180).

Regarding developing countries, the same statistics mentioned

above shows that inflation has fallen sharply since 1995, recording rates of

22.1% and 14.6% respectively in 1995 and 1996 against 47.5% in 1993 and 51.8%

in 1994. During 1997, inflation has fallen sharply again to 9.2% and then

increased to 10.3% in 1998. In Asia the rate of inflation fell to 4.8% in 1997

against 8.2% in 1996 while in Africa, he settled in less than half of the new

1996 (11.1% in 1997 against 25.9% in 1996) due to reforms and macroeconomic

stabilization policies implemented in the country market. In 1998, inflation

was reduced to 8.7% in Africa, while in Asia it rose again to 8.0% on the trace

of the crisis that rocked the continent.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the inflation rate was 13.7% and 10.3%

respectively in 1997 and 1998 against 32.3% in 1996.

After the years of double-digit inflation in 1990-95 and

predominantly high inflation in 1996-2000, global rates fell to less than 5% in

2000-05. The most marked decreases were recorded in the transition countries,

and the most stable, continuously low and decreasing inflation was recorded in

the developed countries (ILO 2005:32).

The financial crisis which occurred in the United States in

the second half of 2006 and became acute in 2008 continues to affect seriously

the world economic outlook. In USA, inflation was 3.8% on average at the

end of the year 2008 against 2.9% recorded in 2007 then declined by 0.3% in

2009. In the Euro Zone, harmonized inflation was 3.3% while it was 2.1% in

2007. The last estimates of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) highlight a

world economic growth rate of 3.2% at the end of 2008 against 5.2% recorded in

2007 and stood at 0.3% in 2009. (NBR, 2009:15)

The following table shows annual percentage change of

inflation by region of the recent years from 2005 to 2009

Table 1: Inflation by region (annual %

change)

1.2 The research Problem

Thanks to the direct control of credit and prices, inflation

was kept at a low level during the 1980s, an average rate of 4.7%. In the

context of the 1990-1994 war, inflation was bound to increase and it indeed

reached 64% in 1994. During the 1996-2000 period, the progressive restoration

of institutions and security in the entire country, the control of public

expenditure and monetary policy allowed the country to contain inflation at an

average level of 5.4%. During the 2001-2005 periods, inflation was kept at an

average rate of 6.7%. (Musoni 2009:5)

Rwanda's economy in 2008 developed in an unfavorable

international economic environment characterized by a worst inflationary shock

and the current global financial crisis. The world economy experienced

important inflationary shocks during the first half of 2008 due essentially to

the increase in world oil and food prices. On annual average, inflation in

advanced economies was 3.4% in 2008 against 2.2% in 2007.

Despite the unfavorable international environment, Rwandan

economy continued to perform well with the real GDP growth rate of 11.2% in

2008 following 7.9% recorded in 2007. This growth was mainly due to a strong

recovery in the agriculture sector which registered a growth rate of 15%

compared to 0.7% in 2007 and a noticeable improvement both in industry and

service sectors which increased by 10.7% and 7.9% respectively. The secondary

sector growth was driven mainly by good performance in the construction and

public works sub-sector (26%) and production of electricity (16.9%) despite a

decline in manufacturing of 4.1%. (NBR 2008:3)

According to the NBR (2009:4), the overall inflation

accelerated from 6.6% in December 2007 to 22.3% in December 2008, despite the

improvement in agriculture production and the low growth of broad money. In

terms of annual average, the inflation in 2008 reached 15.4%, against 9.1% in

2007 due to decline in import prices, good performance of agricultural

production, annual average inflation dropped to 10.3% from 15.4% in 2009.

The inflationary pressures resulted particularly from the

international fuel and food prices. Compared to the year 2007, terms of trade

deteriorated by 16.5% in 2008, their index falling from 150.5 in 2007 to 125.7

in 2008. Contrary to the year 2007 when the export average value had increased

more than the import average value (18.2% compared to 2.2%), trends were

reversed in 2008.

The questions that come to mind after considering these issues

concerns factors that explain inflation in Rwanda. Relatedly, is there an

economically interpretable relationship among Consumer prices Index, output,

interest rate, money supply and the exchange rate? And lastly, how can we use

these variables to forecast future inflation rate in Rwanda?

1.3 Research objectives

In view of the above research problem, the broad objective of

this study analyzes statistically factors affecting inflation rate in Rwanda.

This involved specifying and estimating an inflation regression model with the

consumer prices index as the dependent and, gross domestic product, interest

rate, money supply and exchange rate as the explanatory variables.

The specific objectives of the study therefore were:

i. To determine the effect of Money supply on the inflation

rate in Rwanda;

ii. To determine the effect of the gross domestic product

(output) on the inflation rate in Rwanda;

iii. To determine the effect of exchange rate on the inflation

rate in Rwanda;

iv. To determine the effect the interest rate on the inflation

rate in Rwanda.

1.4 Research Hypotheses

In consistent with specific objectives above, this study tests

the following null hypotheses:

i. H0 : Money supply has no effect on inflation rate in

Rwanda.

H1 : Money supply has a significant positive effect on

inflation rate in Rwanda.

ii. H0 : Output has no effect on inflation rate in Rwanda.

H1 : Output has a significant positive effect on inflation

rate in Rwanda.

iii. H0 : Exchange rate has no effect on inflation rate in

Rwanda.

H1 : Exchange rate has a significant positive effect on

inflation rate in Rwanda.

iv. H0 : Interest rate has no effect on inflation rate in

Rwanda.

H1 : Interest rate has a significant positive effect on

inflation rate in Rwanda.

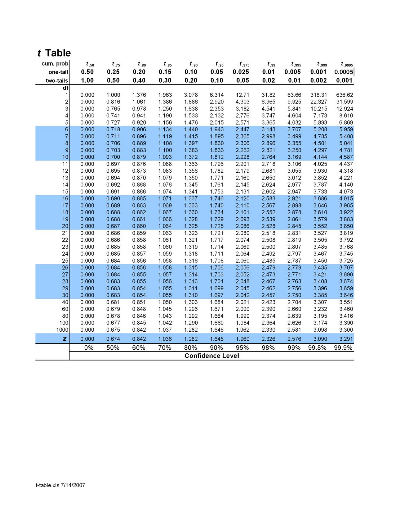

The student's t-test was used

to test the above hypotheses at the 5% significance level.

1.5 Significance of Study

In an inductive perspective, this study increases our

understanding about the effect of studied variables on inflation rate in Rwanda

hence, it can be used by decision markers to control or carry out the problem

of inflation based on correlation coefficient of each variable to the

inflation. In a deductive perspective, this study helps the researcher to

increase deep knowledge about the frequent fluctuations of the prices on the

market; it will also help my community to ascertain further studies about the

inflation based on our achievement.

1.6 Scope of the study

Our research as any other scientific work is limited in time,

space and in the domain. In time, we focused our analysis on the period from

1990 to 2009 because the period allowed us to search recent data related to our

subject.

Regarding the delimitation of space, our study focuses on

Rwandan territory. In the field, our study focuses on aggregate macroeconomic

variables between inflation and its possible effects on the economy.

1.7 Organization of the study

This study have five chapters which will be organized as

follows: Chapter one is an introduction giving the background of the study,

research problem, research objectives, research hypotheses, significance of the

study, hypothesis, and scope of the study. Chapter two is the literature

review. Chapter three presents a discussion of the methodology adopted for the

empirical analysis, followed by the results and discussion of the empirical

analysis in chapter four. The last chapter considers the conclusion and

recommendations.

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 DEFINITION OF KEY CONCEPTS

The concept is a prerequisite for any research. To avoid using

vague terms and to fight against any kind of ambiguity, it is important to

begin by defining the details of the key concepts of the study. The concepts

defined in this study are: Inflation, Consumer Price Index, Gross Domestic

Product, Interest Rate, Money Supply, Exchange rate.

2.1.1 Inflation

In economics, inflation is a rise in the general

level of prices of goods

and services in an economy over a period of time. Moreover different economists

have defined inflation as follows: According to the Kumar (1993:258)

«inflation refers to the persistent, steady and continuous rise in the

general prices of all outputs as well as inputs».

G. Crowther defines inflation as «a stage in which value

of money is falling i.e. prices are rising.» Thus, inflation does not

refer to the rise of price of one or two commodities, but the general rise in

prices of all goods.

Prof. Coulburn has defined inflation as «too much money

chasing too few goods» (Kumar and Mittal 2002:168).

According to Peterson (1977: 294) popularly inflation refers

to the «sustained rise in the general price level and is

generally measured by changes in the consumer price index».

A. Different types of inflation

According to the Kurman (1993: 260) Inflation has been divided

into many kinds on the basis of different criteria like (1) Speed of inflation,

(2) cause of inflation, (3) Control etc.

a. Creeping, Walking, Running and Galloping

inflation: on the basis of rapidity of the rise in the prices

inflation has divided into 4 types: creeping, walking, running and galloping

inflation. However the different between these types of inflation is rather

matter of degree only. Different names are given to different speed of

price-rise.

When the price rises very slowly by about 3%, we call it

creeping inflation, it is very mild and does not cause any harm to the economy.

During walking inflation the rise in prices becomes more marked and it gives

the danger signal of the occurrence of running inflation. When the prices

increase by more than (say 10%) per annum, there is running inflation, which

causes great harm to the economy. Running inflation gives rise to the galloping

inflation, which is also known as jumping or hyper-inflation. During this

situation, there is acute shortage of goods and extra ordinary expansion of

currency and credit and it is very alarming and has disastrous consequences.

b. Demand-pull and Cost-push inflation: On

the basis of cause of inflation, it has been

divided into two types: Demand-pull inflation and Cost-push inflation.

Demand-pull inflation is one kind of inflation which is caused by the excess

demand for goods and services. This inflation takes place when the general

prices rise as a result of growing demand for goods and services in relation to

their supply.

On the other hand cost-push inflation refers to the situation

of steady rise in prices which are mainly caused by the continuous rise in the

cost of production of goods and services. It is the most important and popular

type of inflation in developing countries. The cost of production of the

producers rises continuously. Higher cost leads to higher prices always.

If the prices rise only due to higher wages then we call it

«wage-induced» inflation. In other words the wage induced inflation

occurs when the money wage rises faster than the labour productivity. Sometimes

cost-push inflation becomes «profit-push» inflation, when the

monopoly producers charge higher prices and enjoy higher profit margins.

c. Open inflation and suppressed inflation:

open inflation refers to the unrestricted price-rise. When prices rise

continuously and substantially, without any regulation, the phenomenon is

called `open' inflation. During this inflation, the increase in demand directly

leads to the ever increasing prices.

However, open inflation does not occur nowadays. No government

allows such situation to take place. There are always some regulatory methods

adopted by the governments to control the rise in price.

On the other hand, Suppressed inflation is regulatory

inflation, known as latent inflation. The control measures sometimes may

succeed for a short period. But in the long run the suppressed inflation may

become uncontrollable and become open or hyper.

d. Imported inflation: Inflation due to

increases in the prices of imports, increases in the prices of imported final

products directly affect any expenditure-based measure of inflation. Increases

in the prices of imported fuels, materials, and components increase domestic

costs of production, and lead to increases in the prices of domestically

produced goods. Imported inflation may be set off by foreign price increases,

or by depreciation of a country's exchange rate.

B. Causes of inflation

There are many different reasons that can account for the

inflation in goods and services, depending on a number of factors:

Ø Cost Push Inflation

Cost-push inflation occurs when businesses respond to rising

production costs, by raising prices in order to maintain their profit margins.

There are many reasons why costs might rise:

a) Rising imported raw materials costs

b) Rising labour costs: caused by wage

increases which exceed any improvement in productivity.

c) Higher indirect taxes imposed by the

government: for example a rise in the rate of excise duty on alcohol

and cigarettes, an increase in fuel duties or perhaps a rise in the standard

rate of Value Added Tax or an extension to the range of products to which VAT

is applied.

Ø Demand Pull Inflation

Demand-pull inflation is likely when there is full employment

of resources. In these circumstances an increase in aggregate demand will lead

to an increase in prices. Aggregate demand might rise for a number of

reasons:

a) A depreciation of the exchange rate, which

has the effect of increasing the price of imports and reduces the foreign

price. If consumers buy fewer imports, while foreigners buy more exports,

Aggregate Demand will rise. If the economy is already at full employment,

prices are pulled upwards.

b) A reduction in direct or indirect

taxation. If direct taxes are reduced consumers have more real

disposable income causing demand to rise. A reduction in indirect taxes

will mean that a given amount of income will now buy a greater real volume of

goods and services.

c) The rapid growth of the money supply when

the monetary authorities permit an excessive growth of the supply of money in

circulation beyond that needed to finance the volume of transactions produced

in the economy.

d) Rising consumer confidence and an increase in the

rate of growth of house prices: both of which would lead to an

increase in total household demand for goods and services

e) Faster economic growth in other countries:

providing a boost to exports overseas.

Ø The wage price spiral -

«expectations-induced inflation»

Rising expectations of inflation can often be self-fulfilling.

If people expect prices to continue rising, they are unlikely to accept pay

rises less than their expected inflation rate because they want to protect the

real purchasing power of their incomes.

C. Measuring Inflation

According to Report of European Central Bank (Jan 2009:25)

Most countries have a simple common-sense approach to measuring inflation,

using the so called «Consumer Price Index» (CPI).

For this purpose, the purchasing patterns of consumers are

analyzed to determine the goods and services which consumers typically buy and

which can therefore be considered as some how representative of the average

consumer in an economy. As such they do not only include those items which

consumers buy on a day-to-day basis (for example bread and fruit), but also

purchases of durable goods (for example cars, Computer, washing machines, and

so on.) and frequent transactions (for example rents). Putting together this

«shopping list» of items and weighting them according to their

importance in consumer budgets leads to the creation of what is referred to as

a «market basket».

Each month, a host of «price surveyors» checks on

the prices of these items in various outlets. Subsequently, the costs of this

basket are then compared over time, determining a series for the price index.

The annual rate of inflation can then be calculated by expressing the change in

the costs of the market basket today as a percentage of the costs of the

identical basket the previous year.

However, the developments of the price level as identified by

such a basket only reflect the situation of an average» or representative

consumer. If a person's buying habits differ substantially from the average

consumption pattern and thus from the market basket on which the index is

based, that person may experience a change in the cost of living that is

different to the one shown in the index. There will therefore always be some

people who experience a higher «inflation rate» for their

«individual basket» and some who face a lower «individual rate

of inflation». In other words, the inflation measured by the index is only

an approximate measure of the average situation in the economy; it is not

identical to the overall price changes faced by each individual consumer.

2.1.2 Consumer Price Index

International Labour Office (ILO) defined consumer prices

index (CPI) as index numbers that measure changes in the prices of goods and

services purchased or otherwise acquired by households, which households use

directly, or indirectly, to satisfy their own needs and wants.

According to the National Institute of Statistic of Rwanda,

The CPI is a measure of the average change over time in the prices of consumer

items goods and services that people buy for day-to-day living. The CPI is a

complex construct that combines economic theory with sampling and other

statistical techniques and uses data collected each month to produce a timely

measure of average price change for the consumption sector of the Rwandan

economy (NISR: March 2010)

The CPI can be intended to measure either the rate of price

inflation as perceived by households, or changes in their cost of living (that

is, change in the amounts that the households need to spend in order to

maintain their standard of living).

In practice, most CPI are calculated as weighted averages of

the percentage price changes for specified set, or «basket», of

consumer products, the weights reflecting their relative importance in

household consumption in some period. Much depend on how appropriate and timely

the weights are. (ILO 2004:4).

However there is some criticism in calculation of this CPI

whereby the prices collected were not a fair sample of the prices that actually

existed for goods of equal quality. According to the Morgan (1947:29) CPI

neglect to consider the following:

1. Underreporting of prices by stores and large rise in prices

of important goods not included in the index.

2. Disappearance of low grades of goods and deterioration in

the quality of goods priced.

3. Large retail-price increase in smaller cities not covered

by the index

Structure and composition of consumer price index in

Rwanda

According to the National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda

(CPI October 2009), The CPI is a Modified Laspeyres index that covers

household consumption as it is used by national accounts. The reference

population for the CPI consists of all households living in urban areas in

Rwanda.

The household basket includes 1,136 products observed in many

places spread all over the administrative centers of all provinces in Rwanda.

All kinds of places of observation are selected: shops, markets, services, etc.

More than 29,200 prices are collected every month by enumerators of the

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda and of the National Bank of

Rwanda.

The weights used for the new index (CPI of the Base year of

February 2009) are the result of the Household Living Conditions Survey (EICV

II) conducted in 2005-2006 with a sample of 6,900 households.

The basket used in measuring CPI by NISR is composed by the

following division of commodities:

1. Food and non-alcoholic beverages (Bread and Cereals, Meat,

Fish, Vegetables, Non-alcoholic beverages) 2.Alcoholic beverages and tobacco

3.Clothing and footwear 4.Housing, water, electricity, gas and other fuels

5.Furnishing, household equipment and routine household maintenance 6.Health

7.Transport 8.Communication 9.Recreation and culture 10.Education

11.Restaurants and hotels 12.Miscellaneous goods and services.

2.1.3 Gross Domestic

Product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is the sum of the market values

of all final goods and services produced in a country (that is, domestically)

during a specific period using that country's resources, regardless of the

ownership of the resources (Richard 2004:11).

In other words, GDP refers to the market value of the flow of

final goods and services within the domestic territory of the country during

the period of one year, inclusive of the consumption of fixed capital. Using

the product approach, it is estimated as the sum total value

added by all the producing units within the domestic territory of the country.

In terms of income approach, it is estimated as the sum total

of compensation of employees, operating surplus, mixed incomes of the self

employed, net indirect taxes and consumption of fixed capital. And, in terms of

expenditure approach, it is the sum total of private

consumption, government consumption, gross domestic capital formation and net

exports. (Jain and Khanna 2007: 95).

Gross domestic product comprises Gross domestic product at

factor cost and at market price. In the words of Hanson, «The Gross

domestic product at factor cost is the sum of net value added by all the

producers in the domestic territory of the country and the consumption of fixed

capital in an accounting year». In contrary, according to the Dernburg

«Gross domestic product at market price is defined as the market value of

the output of final goods and services produces in the domestic territory of a

county during an accounting year».

2.1.4 Interest rate

According to the encyclopedia dictionary, an

interest rate is the price

a borrower pays for the use of

money they borrow from another

borrowee, for instance a small company might borrow capital from a bank to buy

new assets for their business, and the return a lender receives for deferring

the use of funds, by lending it to the borrower. Interest rates are fundamental

to a

Capitalist society.

Interest rates are normally expressed as a percentage rate over the period of

one

Gregorian year.

The interest rate changes when money is loaned the lender

delays spending the money on consumption goods. Since according to time

preference theory people prefer goods now to goods later, in a free market

there will be a positive interest rate.

The interest rate comprises the nominal and the real interest

rate, the nominal interest rate refers to the amount, in money terms, of

interest payable as opposed to the real interest rate which measures the

purchasing power of interest receipts, is calculated by adjusting the nominal

rate charged to take

inflation into account.

2.1.5 Money Supply

Money supply or money stock is the total amount of

money available in an

economy at a particular

point in time. There are several ways to define "money", but standard measures

usually include currency in circulation and demand deposits.

Moreover, Economists define money as anything that is

generally accepted in payment for goods and services or in repayment of debts.

Currency, consisting with notes and coins is one of type of money. Define money

as currency is to narrow because checks are also accepted as payment for

purchases, checking account deposits are considered as money. Other deposits

such as savings deposits can in effect function as money if they can be quick

and easily converted into currency or checking account deposits.

There are different measures of money:

1. The narrowest measure of money (M1) in Rwanda includes the

currency in circulation out the banking sector (CC) and checking account

deposit (CD) in other words, narrow money measures cover highly liquid forms of

money (Money as means of exchange).

2. The broad monetary aggregate (M2) in Rwanda adds to M1

savings deposits in Rwf and in foreign currency. It includes the less liquid

forms (Money as a store of value).

2.1.5 Exchange rate

The exchange rate is the price at which one the national money

can be exchanged for another (When transactions are permitted). For example, a

common exchange rate is the Rwandan franc/US dollar exchange rate. If the

RWF/USD exchange is 5.80, this means that 580 Rwandan franc will buy one US

dollar.

The changes in the value of the exchange rate over time are

referred to as appreciations or depreciations. A currency appreciates when its

value rises, relative to another currency, and depreciates when its value

falls, relative to another currency.

2.2 THEORETICAL

FRAMEWORK

A great deal of economic literature concerns the determinants

and causes of inflation, in which inflation's role in the economy has been at

the center of economic studies and has been debated for a long time.

There are three main schools of thought which attempt to

explain the main determinants of inflation. First, The classical which revolved

around the quantity theory of money,

Blinder (2002), a representative of the second school of

thought, the Keynesian economists, states that the main determinants of

inflation are aggregate demand in the economy rather than the money supply.

Thirdly, the monetary approach led by Milton Friedman,

Friedman and Schwartz (1970), who wrote an influential book on the monetary

history of the United States, argue that "inflation is always and everywhere a

monetary phenomenon". Whereas Neo-Keynesians and other critics of monetarism

argue that the demand for money is directly linked to supply and that the

demand for money cannot be predicted. Stiglitz and Greenwald (2003) have

proposed that the relationship between inflation and money supply growth cannot

be separated for ordinary inflation, in contrast to hyperinflation, which is

mostly considered an effect of monetary policy.

A. Classical theory of inflation

The classical economists' view of inflation revolved around

the quantity theory of money, and this theory was in turn derived form the

Fisher Equation of Exchange.

According to Fisher's Formula, we how MV = PQ. Here M

represents that the average number of currency in circulation during a certain

period; V represents the velocity of money circulation; P represents the price

index of goods and services and Q represents transaction volume of goods and

services. Fisher recognized that V and Q are invariable because V is decided by

social system and custom and Q is stable under the condition of sufficient

employment. Therefore, to some extent, the formula means the Quantity Theory of

Money (IBR, 2009:42).

Therefore the come to the conclusion that:

M M  P P

In other words, increases in the money supply would lead to

inflation. The message was simple: Control the money supply to control

inflation.

B. Keynesian view of inflation

Keynes didn't agree with the classical economists. In fact the

easiest way to look at Keynesian theory is to see the argument he gave for

Classical theory being wrong. The key to the classical view of inflation was

the Quantity Theory of Money. This theory revolved around the Fisher Equation

of Exchange as we have seen above.

Keynes once again rejected this theory. He argued that

increases in money supply would not inevitably lead to increases in inflation.

Increasing M may instead lead to a decrease in V. in other words the average

speed of circulation of money would fall because there was more of it about.

Alternatively, the increase in M may lead to an increased in T

(Number of transactions), because Keynes disputes the assumption that the

economy will find its own equilibrium. It may be in a position where there is

insufficient demand for full employment and in that case increasing the money

supply will fund extra demand and move the economy closer to full employment.

Keynesians tend to argue that inflation is more likely to be cost-push

inflation or from excess levels of demand. This is usually termed demand-pull

inflation (Robert J. Gordon 1988: )

According to the Keynesians, the natural level of gross

domestic product is a level of GDP where the economy is at its optimal level of

production. If GDP increases beyond its natural level, inflation will

accelerate as suppliers increase their prices. If GDP decreases below its

natural level, inflation will decelerate as suppliers attempt to fill excess

capacity by lowering prices.

Keynes argued that money has no significant relationship with

inflation, but inflation is an outcome of the goods market. He proposed the

"inflationary gap" model to explain the change in price level, (Keynes 1936).

But Pigou (1949) rejected the inflationary gap theory. He placed attributed

inflation to the increase in money income. According to Pigou, inflation exists

when money income increases more than the income earning capacity.

The most popular neo-classical economic critique of Keynesian

economic theory is by Lucas (1976), who argues that rational expectations will

defeat any monetary or fiscal policy. The new Keynesian argument is that this

critique only applies if the economy has a unique equilibrium at full

employment, and that rational expectations models do not produce any simple

result. They claim that because of price stickiness, there are a variety of

possible equilibriums in the short run.

C. Monetarists' theory of inflation

Much of the Monetarists' theory is a development of earlier

Classical

theoretical work. Their main contribution is in updating many of these ideas to

fit them into a more modern context.

Classical economists suggested that V would be

relatively stable and T would (as we have seen above) always tend to

full employment. Friedman developed this and tested it further, coming to the

conclusion that V and T were both independently determined in

the long-run. The conclusion from this was that:

M M  P P

If the money supply grew faster than the underlying growth

rate of output there would be inflation. Inflation would be bad for the economy

because of the uncertainty it created. This uncertainty could limit spending

and also limit the level of investment.

Apart from the above schools of thought

which was undertaken to explain the main determinants of inflation, other

theories have been illustrated

Balance of payments and forcing a depreciation of the exchange

rate, The interactions between fiscal policy and inflation are particularly

highlighted in Razin and Sadka (1978:239) and Bruno and Fisher (1990: 353).

This category indicates the change in money supply and real exchange rate as

sources of the inflation

Henry Hazlitt (1978:111) believes that one of the reasons why

inflation is persistently advocated by Keynesians and others is that it is

thought to increase the profitability of business. This is, in fact, an

essential part of the argument of those who believe that inflation tends to

bring full employment. By improving the outlook for profits, it leads

enterprises to start new businesses or to expand old businesses, and therefore

to take on more workers.

2.3 EMPIRICAL FRAMEWORK

Currently, the quantity theory of money is widely accepted as

an accurate model of inflation in the long run. Consequently, there is now

broad agreement among economists that in the long run, the inflation rate is

essentially dependent on the growth rate of money supply. However, in the short

and medium term inflation may be affected by supply and demand pressures in the

economy, and influenced by the relative elasticity of wages, prices and

interest rates (Federal Reserve Board, July 2004)

Sargent and Wallace believe that budget deficit could increase

inflation because of their preponderance in the growth of money supply, point

out that this deficit will become ever larger, because of cumulative of effect

of interest payments (David 1992: 204). This idea is supported by Liviatan and

Piterman (1986: 324) «The most commonly cause of inflation is the

government budgets deficit» according to this explanation, the government

prints money to finance the deficit, and as long as the demand for money is

less that unit elastic, a larger real deficit will result a higher inflation

rate.

The more sophisticated view was expounded by Irving Fisher

(1926:785-792): When the dollar is losing value, or in other words when the

price level is rising, a businessman finds his receipts rising as fast, on the

average, as this general rise of prices, but not his expenses, because his

expenses consist, to a large extent, of things which are contractually fixed. .

. . Employment is then stimulated for a time at least.

Coe and McDermott (1977) in a study of 13 Asian economies,

highlights the fact that: just as in industrialized countries, inflation in

developing countries indicates an overheated economy and is influenced by a

variable of activity. The output gap and a measure of activity level in the

world are the sources that are suggested by this category.

According to Henry Hazlitt (1978:92) for many years it has

been popularly assumed that inflation increases employment. This belief has

rested on both naive and sophisticated grounds. The naive belief goes like

this: When more money is printed, people have more "purchasing power"; they buy

more goods, and employers take on more workers to make more goods.

Another reason of the persistent causes of inflation revealed

by Henry Hazlitt (1978:118) is the perennial demand for cheap money. The

chronic complaint of businessmen, and still more of politicians, is that

interest rates are too high. The popular complaint is directed especially

against the rate for home mortgages.

Chopra (1985:693) expresses the idea that inflation must have

a strong autoregressive component from adjustments in relation to expected

inflation. This category indicates a source of inflation, its own past

achievements.

Empirical results regarding the inflationary effect of

official exchange rate depreciation in cross-country and individual country

studies are also conflicting. For example, Canetti and Greene (1992:37),

studying a number of African countries, report a failure in their attempt to

identify which between exchange rate depreciation and monetary growth is a more

important cause of inflation.

Chhibber and Shaffik (1992:107) do not find a direct

relationship between official exchange rate changes and inflation in Ghana.

According to them, official devaluations had a positive effect on the budget

and were therefore anti inflationary. Their study found that the parallel

market exchange rate had a stronger influence on inflation compared with the

official exchange rate. However, Sowa and Kwakye (1993:50) claim that Chhibber

and Shafik (1992) emphasize monetary factors at the expense of supply factors

in Ghana and conclude that the supply constraint (output) was the main force

behind inflation.

Hyuha (1992:73) found that the devaluations of the official

exchange rate had a push on domestic prices in Uganda. The parallel rate was

also a significant determinant of inflation. Kasekende and Ssemogerere (1994:

62) reached a similar conclusion for the period 1987-1992, using monthly

data.

Ball and Mankiw (1995: 161) examines another source of

inflation, focusing on the supply of goods and services and the «cost

shock» that is to say, the movement of prices specific price level. To

capture the cost shocks, this category indicates changes in the prices index

for petroleum and petroleum product not as source of inflation.

Tsalinski and Kyle (2000: 39) analyzed the determinants of

Bulgarian inflation in the period from 1991 to 2000 using monthly data.

Bulgarian inflation has been shown to have experienced two radically different

regimes over the past decade. The dividing point between the two regimes is the

spring of 1997 when the hyperinflationary trend of the prior period was ended

by the institution of a currency board. They found that inflation during the

previous period had been determined in large part by monetary growth and to

some extent by past inflation. Inflation after the currency board was

established was no longer dependent upon monetary growth.

Ghavam Masoodi and Tashkini (2005:42), to investigate the long

term relationship between the inflation rate and its effective factors in Iran,

they used the ARDL method. The results obtained via this research showed that

GDP, the imported goods price index, liquidity and the exchange rate are the

most significant factors contributing to inflation in Iran.

According to Ferdinand GAKUBA (2009: 30) Inflation is thought

to be an outcome of various economic factors. In Rwanda context he choice the

factors from supply side that come from cost-push or mark up relationships

characterized by unit labor cost , import prices and oil prices index in the

long-run; the demand side factors that may cause the demand pull inflation;

monetary factors; and foreign factors. In order to capture the various

determinants of inflation he has combine the methodology developed in Brouwer

and Neil R. Ericsson (1998) and Juselius (1992) for Australia inflation.

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH

METHODOLOGY

The research intends to follow quantitative patterns. For it

to be systematic and intensive process of carrying out data collection, it will

involve some sort of procedures in collecting and analyzing data.

The methodology will follow procedures of quantitative

research because it is based on measurements of quantitative indicators. It is

applicable to the phenomena that can be expressed in terms of quantity that is

easily empirically measured.

3.1 DATA

COLLECTION

3.1.1 Techniques

A technique is defined as all resources and processes that

enable researchers to gather data and information on the research topic (WELMAN

J. C and KRUGER S.J., 2001:34)

Thus, we preferred the documentary techniques which is a

systematic search of all that is written related with the research area such as

books, pamphlets, monographs, unpublished documents, reports, budgets, public

records etc. the documentary technical allows us to choice among the books

available what are useful for our research and help to use the best

resources.

3.1.2 Types and sources of

data

The success of any econometric analysis ultimately depends on

the availability of the appropriate data. It is therefore essential that we

spend some time discussing the nature, sources, and limitations of the data

that one may encounter in empirical analysis.

Time Series Data will be used in our research. A time series

is a set of observations on the values that a variable takes at different

times. Such data may be collected at regular time intervals, such as daily

(example stock prices, weather reports), weekly (money supply figures), monthly

[the unemployment rate, the Consumer Price Index (CPI)], quarterly (GDP),

annually (government budgets), every 5 years (the census of manufactures), or

decennially (the census of population).

Time series data are used heavily in econometric studies but

they present special problems for econometricians; most empirical work based on

time series data assumes that the underlying time series is stationary.

Although it is too early to introduce the precise technical meaning of

stationarity at this juncture, loosely speaking a time series is stationary if

its mean and variance do not vary systematically over time GUJARATI

(2006:26).

Different visits to libraries, internet exploration, and use

of documents provided by National Bank of Rwanda, National Institute of

Statistic of Rwanda, Ministry of finance has been considered useful.

3.2 DATA ANALYSIS

3.2.1 Methods

Method is defined as an ordered set of rules and principles of

intellectual operations to do the analysis to achieve a result (WELMAN J. C and

KRUGER S.J., 2001:36).

At the completion of our work, we have chosen the analytical

method, this method allows to systematically analyzing all information and data

collected. It allowed us to systematically analyze the inflation's relationship

with others macroeconomic variables, to interpret and draw the conclusion.

a. Preparing data for analysis

Data will be entered in the tables where they will be clearly

viewed and checked for errors. After these, they will be entered in the

computer (SPSS software) for analysis.

b. Exploring and presenting data

Once data will have been entered and checked for errors,

analysis will take place .The exploratory data analysis approach for this study

will emphasize the use of diagrams to explore and understand the sense of the

data. During this process, research questions and objectives will be kept in

mind. It will help to formalize the practice of looking for other relationships

in data which have not been thought of initially .So, at this stage, they will

be a request to structure and label clearly each diagram and table to avoid

possible misinterpretation.

c. Analyzing quantitative data

This will involve choosing the appropriate statistics to

describe the data and the choice of the adequate statistics to examine

relationships among data.

At this step, the researcher will be concerned with answering

the question»how do some variables relate to others?» During the

statistical analysis, this question will be answered by testing the likelihood

of the relationship between specific variables. Here, relationships between

Gross domestic product, Money Supply (M2), Interest rate, Exchange

rate and Inflation will be discussed. Testing whether the variables are

significantly associated, the help of a simple regression model does it.

d. The general model of inflation

CPI=f (M2, GDP, LR, ER, ...)

Where

CPI : Consumer Price Index

M2 : Money Supply

GDP : Gross Domestic Product

LR : Lending rate

ER : Exchange rate

Specification of the model

CPI = á M2â

GDPã LRë ERä

ì

The model will be linealized by using logarithmic function.

Hence

Log CPI= log á+ â logM2+ã

log GDP +ë log LR +ä log ER +log ì

Whereby â, ã, ë and ä

are parameters of the model and log ì is the error

terms

e. Describing data using statistics/data

measurements

According to GUJARATI (2006:126) there are two mutually

complementary approaches of hypothesis testing which is concerned with

developing rules or procedures for deciding whether to reject or not reject the

null hypothesis, namely confidence interval and test of significance. Both

these approaches predicate that the variable (statistic or estimator) under

consideration has some probability distribution and that hypothesis testing

involves making statements or assertions about the value(s) of the parameter(s)

of such distribution.

At this step the, T-test (the Student test)

will be used to test the significance of the variables and

F-test (Fischer' test) will be used to test the significance

of the model.

The t-test is probably the most commonly used

Statistical

Data Analysis procedure for hypothesis testing. Actually, there are several

kinds of t-tests, but the most common is the "two-sample t-test" also known as

the "Student's t-test" or the "independent samples t-test".

The statistics t-test allows us to answer this question by

using the t-test statistic to determine a p-value that

indicates how likely we could have gotten these results by chance. By

convention, if there is a less than 5% chance of getting the observed

differences by chance, we reject the null hypothesis and say we found a

statistically significant difference between the two groups.

The p-value is a numerical measure of the statistical

significance of a hypothesis test. It tells us how likely it is that we could

have gotten our sample data even if the null hypothesis is true. By convention,

if the p-value is less than 0.05 (p < 0.05), we conclude that the null

hypothesis can be rejected. In other words, when p < 0.05 we say that the

results are statistically significant.

CHAPTER FOUR: DATA PRESENTATION,

ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION

The purpose of this chapter is to present and analyse the

results of the studies conducted on the field. We will first give data

presentation. Then, we will direct the study towards interpretation of result

of SPSS regression analysis.

4.1 DATA PRESENTATION

4.1.1 Table2: EVOLUTION OF CPI,

M2, Real GDP, ER and LR (1990-2009)

|

SN

|

Years

|

Consumer Price Index (CPI)

|

Money Supply (M2)

(In millions Rwf)

|

Real GDP (Base Year: 2000)

(In millions of Rwf)

|

Exchange rate (ER) In US Dollars

|

Lending rate (LR) in %

|

|

01

|

1990

|

19.00

|

31,893.70

|

213,533.0

|

83.70

|

9.96

|

|

02

|

1991

|

22.70

|

33,730.30

|

239,310.0

|

125.16

|

13.65

|

|

03

|

1992

|

24.90

|

37,900.50

|

276,488.0

|

133.94

|

15.00

|

|

04

|

1993

|

28.00

|

37,966.30

|

284,368.0

|

144.24

|

13.61

|

|

05

|

1994

|

55.70

|

32,221.70

|

165,800.0

|

140.70

|

12.88

|

|

06

|

1995

|

55.70

|

62,645.00

|

339,143.0

|

262.18

|

16.07

|

|

07

|

1996

|

59.80

|

69,856.90

|

424,130.0

|

306.82

|

16.17

|

|

08

|

1997

|

67.00

|

90,163.60

|

558,281.0

|

301.53

|

16.22

|

|

09

|

1998

|

71.20

|

91,984.50

|

621,388.0

|

312.31

|

17.13

|

|

10

|

1999

|

69.40

|

98,056.30

|

606,991.0

|

333.94

|

16.84

|

|

11

|

2000

|

72.20

|

111,254.70

|

676,099.0

|

389.70

|

16.99

|

|

12

|

2001

|

74.60

|

121,418.20

|

741,872.0

|

442.99

|

17.29

|

|

13

|

2002

|

76.10

|

144,567.90

|

781,468.0

|

475.37

|

16.37

|

|

14

|

2003

|

81.70

|

167,523.50

|

955,164.0

|

537.66

|

17.05

|

|

15

|

2004

|

91.70

|

187,225.00

|

1,138,470.0

|

557.45

|

16.48

|

|

16

|

2005

|

100.00

|

218,372.30

|

1,332,910.0

|

557.82

|

16.07

|

|

17

|

2006

|

108.90

|

285,646.30

|

1,563,830.0

|

551.71

|

16.07

|

|

18

|

2007

|

118.80

|

375,273.50

|

1,866,120.0

|

546.96

|

16.19

|

|

19

|

2008

|

137.10

|

395,808.80

|

2,063,505.5

|

546.85

|

16.51

|

|

20

|

2009

|

146.60

|

404,365.40

|

2,187,000.0

|

568.00

|

16.49

|

Source: ECONSTATS, NBR, NISR (Annual reports:

2009; 2006; 2003; 2000; 1997; 1995)

4.2 DATA ANALYSIS AND

INTERPRETATION

4.2.1 Correlation between

variables

The correlation coefficient is a number between -1 and +1 that

measures both the strength and direction of the linear relationship between two

variables.

The magnitude of the number represents the strength of the

correlation. A correlation coefficient of zero represents no linear

relationship (the scatter plot does not resemble a straight line at all), while

a correlation coefficient of -1 or +1 means that the relationship is perfectly

linear (all of the dots fall exactly on a straight line).

The sign (+/-) of the correlation coefficient indicates the

direction of the correlation. A positive (+) correlation coefficient means that

as values on one variable increase, values on the other variable tend to also

increase; a negative (-) correlation coefficient means that as values on one

variable increase, values on the other tend to decrease, that is, they tend to

go in opposite directions.

A Scatter plot here was used to determine if there is

correlation between two variables. Moreover they are things to consider when

using scatter plots like that a direct or strong correlation does not

necessarily imply a cause-and-effect relationship. If a scatter plot shows

signs of correlation, investigate further for confirmation.

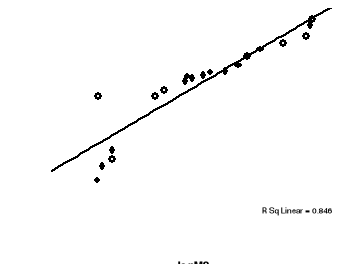

A. Correlation between Consumer

Price Index and Money Supply (M2)

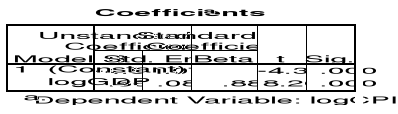

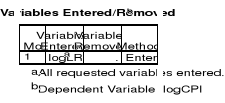

1. Summary of output from SPSS regression analysis

between CPI and M2

|

Variables

|

Coefficients

|

t

|

P-Value

|

|

Constant

|

-3.119

|

-4.261

|

0.000

|

|

Money Supply (M2)

|

0.629

|

9.930

|

0.000

|

|

R = 0.92 Confidence intervals = 95%

F= 98.605 R Squared =0.846 Model significance = 0.000

|

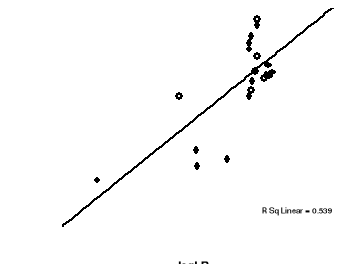

2. Graph1: Trends in CPI and

M2, 1990-2009

This scatter plot describes a positive trend; there is a weak

positive correlation between CPI and M2. In other words, the value of CPI

increases slightly as the value of M2 increases.

Thus, our regression analysis shows that the volume of money

supply is positively related to the consumer price index; coefficient has a

positive sign and also is statistically significant at 0.001 Since observed

t-value (9.930) lies in the critical region we reject the null hypothesis.

Therefore, we confirm the alternative hypothesis says that Money supply has a

significant positive effect on inflation rate in Rwanda.

It also shows results from an increase of one unit of Money

supply would result to an increase in Consumer price index by 62.9 %.

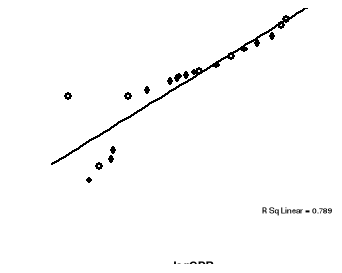

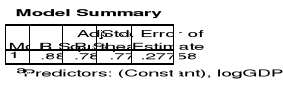

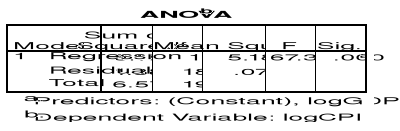

B. Correlation between Consumer

Price Index and Real Gross Domestic Product

1. Summary of output from SPSS regression analysis

between CPI and GDP

|

Variables

|

Coefficients

|

t

|

P-Value

|

|

Constant

|

-4.678

|

-4.334

|

0.000

|

|

Gross Domestic Product

|

0.661

|

8.203

|

0.000

|

|

R = 0.888 Confidence intervals = 95%

F= 67.335 R Squared = 0.789 Model significance = 0.000

|

2. Graph2: Trends in CPI and GDP,

1990-2009

This shows that there is a correlation between GDP and CPI.

This is known as a weak positive correlation as the line goes up meaning that

if the GDP increases, CPI also increases which differs from the output of

regression analysis of the general model as well as the monetarist theory

whereby an increase in GDP should affect a decrease in CPI.

Consider the observed t-value of Real GDP (8.206) shows that

it lies in the critical region or region of rejection of null hypothesis.

Therefore we accept the alternative hypothesis says that Output has a

significant effect on inflation rate in Rwanda. Since an increase of one unit

in output (Real GDP) affect a decrease of 66.1% in Consumer price index

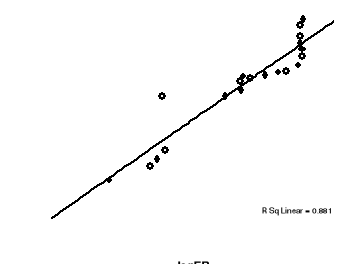

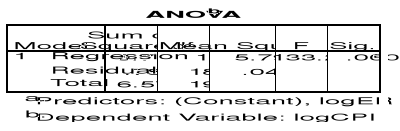

C. Correlation between Consumer Price

Index and Exchange rate

1. Summary of output from SPSS regression analysis

between CPI and ER

|

Variables

|

Coefficients

|

t

|

P-Value

|

|

Constant

|

-1.003

|

-2.229

|

0.039

|

|

Exchange rate

|

0.893

|

11.541

|

0.000

|

|

R = 0.939 Confidence intervals = 95% F=

133.205 R Squared = 0.881 Model significance = 0.000

|

2. Graph3: Trends in CPI and Exchange

rate, 1990-2009

This scatter plot describes weak positive trend between

Exchange rate and CPI, The value of CPI increases slightly as the value of

exchange rate increases. P-value (0.000) is statistical significant, the

t-values of exchange rate (11.541) lies in the critical region. Therefore, we

reject the null hypothesis and confirm the alternative hypothesis says that

exchange rate has a positive effect on inflation rate in Rwanda. In addition

one unitary change in exchange rate affects an increase in consumer price index

by 32.55%

D. Correlation between Consumer Price

Index and Lending rate

1. Summary of output from SPSS regression analysis

between CPI and LR

|

Variables

|

Coefficients

|

t

|

P-Value

|

|

Constant

|

-4.763

|

-2.444

|

0.25

|

|

Lending rate

|

3.255

|

4.586

|

0.000

|

|

R = 0.734 Confidence intervals = 95% F=

21.034 R Squared = 0.539 Model significance = 0.000

|

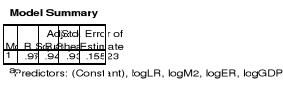

2. Graph 4: Trends in CPI and Lending

rate, 1990-2009

In this graph the plots are not on a completely straight line

but some are near each other and a line tends upward therefore there is a

positive correlation though but not strong. The value of CPI seems to be

related to the value of lending rate, but the relationship is not easily

determined.

Considering the result of the regression analysis, t-values of

lending rate (4.586) lies in the rejection area of null hypothesis and is also

statistical significance as shown by P-value (0.000). As conclusion we accept

the alternative hypothesis says that Lending rate has effect on inflation rate

in Rwanda. Since the change in one unit of lending rate affect an increase by

325.5% in consumer price index.

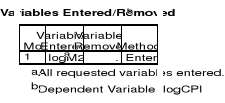

4.2.2 Regression equation of the model

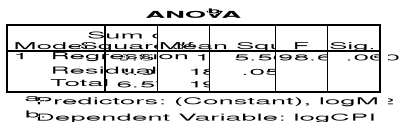

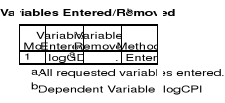

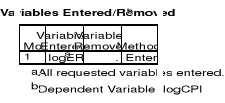

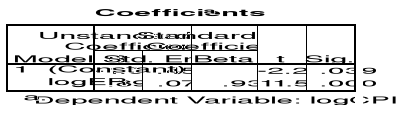

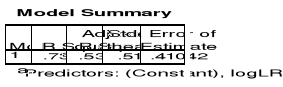

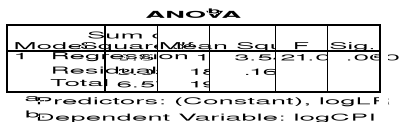

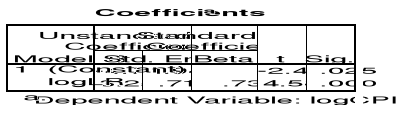

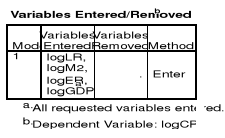

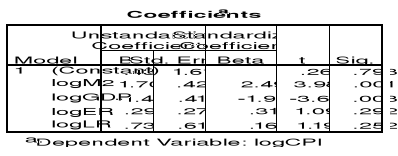

1. Summary of output from SPSS regression

analysis of multivariate

|

Variables

|

Coefficients

|

t

|

P-Value

|

|

Constant

|

0.430

|

0.267

|

0.793

|

|

Money Supply (M2)

|

1.706

|

3.981

|

0.001

|

|

Real GDP (GDP)

|

-1.476

|

-3.603

|

0.003

|

|

Exchange Rate (ER)

|

0.297

|

1.092

|

0.292

|

|

Lending Rate (LR)

|

0.733

|

1.192

|

0.252

|

|

R = 0.972 Confidence intervals = 95% F=

64.470

R Squared = 0.945 Model significance = 0.000

|

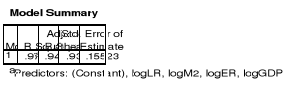

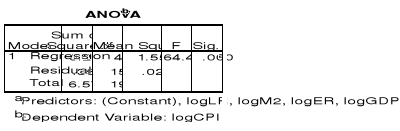

Examining the output from this regression analysis; we look to

the p-value of the F-test to see if the overall model is significant. With a

p-value of zero to three decimal places, the model is statistically

significant. The R-squared is 0.945, meaning that approximately 94.5% of the

variability of CPI is accounted for by the variables in the model. In this

case, the adjusted R-squared indicates that about 94.5% of the variability of

CPI is accounted for by the model; even after taking into account the number of

predictor variables in the model. As explained below, the coefficients for each

of the variables indicates the amount of change one could expect in CPI given a

one-unit change in the value of that variable, given that all other variables

in the model are held constant.

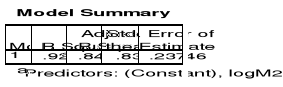

In order to arrive at a more efficient model, variables with

low t-values or incorrect signs in the over-parameterized regression were

excluded.

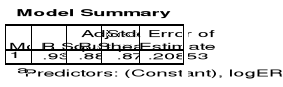

2.

Specification of general model

CPI = 0.43 M21.706

GDP-1.476 ì

Log CPI= 2.7 +1.706 log M2 +1.476 log GDP+

ì

3. Predictive accuracy of the general model

One way to measure the overall predictive accuracy of a

multiple regression model is the R-square value. The interpretation of R-square

is: "The amount of variance in the dependent variable that can be explained by

the model." For our model the R-square value is 0.945, this means the model

explains 94.5% of the variance and so the model will produce perfect predictive

accuracy. The point is, the closer to 1.0 the R-square value is, the better the

model. The closer the R-square value is to 0, the worse the model.

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

5.1 CONCLUSION

Historically, a great deal of economic literature was

concerned with the question of what causes inflation and what effect it has,

forecasting inflation is key for a central bank to adjust its monetary policy

to control inflation. Regardless of its monetary policy framework broad money

growth target, exchange rate target, or inflation target, stabilizing inflation

is a primary objective of monetary policy.

The main goal of this work was to determine the factors

influencing inflation rate in Rwanda. To have this goal reached analytical

method was used, this method allows to systematically analyzing all information

and data collected. As far as data analysis is concerned, specific software

designed for data analysis have been used based on the times series data

collected from different government institutions.

From the findings, Money supply and Real GDP (Output) were

found to be important in determining the level of inflation. The effects of the

two variables conformed to our priori assumptions. Other alternative two

hypotheses were also rejected exchange rate and Lending rate that have not

significant effects on inflation rate in Rwanda. There was no evidence

suggesting the influences of exchange rate and lending rate on inflation, as

both t-tests are not statistical significance. This was tested based on SPSS

software attributes in accordance with the theory given in chapters 2 and 3.

These results collaborate studies on inflation in other African economies like

Chhibber and Shafik (1992: 107 - 133) obtain similar results for Ghana and

Samuel A and Ussif (2001:14) for Tanzania.

5.2 RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the research findings, skills of the researcher and

other constraints accounted, we can conclude this study by giving the following

recommendations for further research.

The outcome of this study does not establish the superiority

of one hypothesis over the other; rather it provides a much boarder perspective

of the complexities of the inflationary process in Rwanda. It also points

towards some of drawbacks of the domestic economic policies as well as the

effects of the external factors influencing the economy which were beyond the

control of the government.

The monetarist assert that inflation everywhere is a monetary

phenomenon and can be controlled by controlling the money supply, thus to

control inflation the government will have to pursue a contractionary monetary

and fiscal policy.

The results indicated that output has a significant effect on

inflation rate in Rwanda. Hence emphasizing in substantial growth in

agriculture sector as well as other economic activities that contribute in

increase of Gross domestic product can help to moderate the rate of

inflation.

Further studies in the areas of domestic supply of agriculture

commodities, imports and exports of agricultural output were suggested in

Rwanda to determine the actual inflationary movements and pertinent policy

implications.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

BOOKS

Damodar N. GUJARATI (2004) «Basic

Econometrics, 4th Edition, McGraw-Hill/ Irwin. Hardcover.

David GOWLAND (1982) «Controlling the money

supply» British Library, Great Britain.

Friedman, M. and Schwartz, A. J. (1970) Monetary

Statistics in the U.S. Estimates, Sources, Method. New York: National

Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Henry HAZLITT «The inflation crisis and how to

resolve it,» Arlington house, New Rochelle, New York.

Irving FISHER, "A Statistical Relation between

Unemployment and Price Changes," International Labor Review, June

1926, pp. 785-92.

KUMAR (First Edition 1993), «An exposition to

economics» Mittal Publication, New Delhi, INDIA.

KUMAR and MITTAL (First Edition 2002), «Monetary

Economics» Anmol publications P.V.T. LTD, New Delhi.

Liviatan N. and Piterman S. (1986), «Accelerating

Inflation and Balance of Payments Crises, 1973--1984,» in The

Israeli Economy, ed. By Yoram Ben-Porath (Cambridge: Harvard University Press),

pp. 320-46.

Musoni J. RUTAYISIRE (2009) «Economic

Liberalization, Monetary Policy and Money Demand in Rwanda:

1980-2005»

Richard YAMARONE (2004) «The trader's guide to

key economic indicators» Library of congress,

Robert J. GORDON (1988), «Macroeconomics: Theory

and Policy», 2nd ed., Chap. 22.4, 'Modern theories of inflation'.

McGraw-Hill.

Stiglitz, J. and Greenwald, B. (2003) Towards A New

Paradigm in Monetary Economics: Cambridge University Press.

Tsalinski, T. and Kyle, S. (2000) «Determinants

of Inflation in the Bulgarian Economy». Cambridge: Harvard

Institute for International Development.

Welman J. C and Kruger S.J.(2001) : «Research

methodology course for the business and administrative sceines» ,

2nd edition , Paris, Durod , page 34-36.

JOURNALS

Agenor, P. and P. MONTIEL. 1996. «Development

Macroeconomics. Princeton»: Princeton University Press.

Ball, L. and Mankiw G. (1995), «Relative Price

Changes as Aggregate Supply Shocks» Quarterly Journal of

Economics, pp: 161-194, February 1995.

Bruno M. and Fischer S. (1990), «Seignorage,

Operating Rules and the High Inflation Trap» Quarterly Journal of

Economies, y. 105 (May), pp: 353-74.

Canetti E. and J. Greene. 1992. «Monetary growth

and exchange rate depreciation as causes of inflation in African countries: An

empirical analysis». Journal of African Finance and Development,

Spring: 36-61.

Chhibber, A. and N. Shafik (1992), «Devaluation

and Inflation with Parallel Markets: An Application to Ghana», Journal of

African finance and Economic Development, Spring, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp.

107 - 133.

Chopra A. (1985), «The Speed of Adjustment of the

Inflation Rate in Developing Countries: A Study of Inertia.» IMF

Staff Papers, Vol. 32, No. 4 (December), pp: 693-733.

Coe, David T. and McDermott J. (1997), «Does the

Gap Model Work in Asia?» IMF Staff Papers, Vol. 44 No.

1, March 1997.

Ghavam MASOODI, Z. and Tashkini, A., (2005). «The

Empirical Analysis of Inflation in Iran» Quarterly Business

Research Letter.No.(36). 75-105.

Hyuha, M. 1992. «Reflections on forex bureau/

parallel and official foreign exchange rates and inflation in

Uganda». Paper presented at the 2nd Conference of the Eastern and

Southern African Economic Association, Dar es Salaam, December.

Jain and Khanna (2007) «Economic concepts and

Methods» V.K (India) Enterprises.

Kasekende, L. and G. SSEMOGERERE. 1994. «Exchange

rate unification and economic development: The case of Uganda,

1987-92». World Development, 22 (8): 1183-98

Keynes, John M., (1936) «The General Theory of

Employment, Interest, and Money.» Macmillan, London.

Lucas, R. (1976) «Macroeconomic policy

Evaluation»: A Critique, in the Phillips Curve and Labor markets.

Paper presented at the Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy,

Amsterdam: North Holland.

Razin A. and Sadka E. (1987), «Economic Policy in

Theory and Practice.» New York: St. Martin's Press.

Rebelo, S. and C.A. Vegh. 1995. «Real effects of

exchange-rate-based stabilisation: An analysis of competing

theories». Discussion Paper No. 1220, London: Centre for Economic

Policy Research.

Samuel A. LARYEA and Ussif Rashid SUMAILA (2001)

«Determinants of inflation in Tanzania» CMI Working

Papers.

Sowa, N.K. and J.K. KWAKYE. 1993. «Inflationary

Trends and Control in Ghana». Research Paper No. 22. African

Economic Research Consortium, Nairobi.

REPORTS