|

MASTER'S THESIS

Investor Sentiment and Short Run IPO

Anomaly:

A Behavioral Explanation of

Underpricing

Ines MAHJOUB

Table of contents

Abstract

..............................................................................................6

INTRODUCTION

.....................................................................................7

Section 1- Short run IPO anomaly and traditional

explanations ......................10

Introduction

.............................................................................................10

I- Underpricing anomaly: a persistent phenomenon that

characterizes IPO market .....11

I-1\ Underpricing definition

......................................................................11

I-2\ A persistent anomaly in time

..................................................................12

I-3\ A persistent anomaly in all countries

.........................................................13

I-4\ A persistent anomaly in all industries

.........................................................15

II- Theoretical explanations of short run

underpricing: A literature review .............15

II-1\ Asymmetric information

..................................................................16

II-1-1\ The issuer is more informed than the investors

.......................................16

II-1-2\ The investors are the most informed

.........................................................19

* Information Revelation Theories

..................................................................19

* Winner's Curse

.....................................................................................22

* Agency conflicts

....................................................................................23

II-2\ Symmetric information

...........................................................................25

II-2-1\ Risk premium

....................................................................................25

II-2-2\ Characteristics of the Initial Public offering

................................................26

* Risk

......................................................................................................26

* Issue size

.............................................................................................27

* Bargaining power

....................................................................................28

II-2-3\ Lawsuit avoidance: legal liability

.........................................................29

II-2-4\ Underpricing as a substitute of marketing expenditures

..............................30

II-2-5\ Internet Bubble

...........................................................................31

II-2-6\ Price stabilization and partial adjustment

................................................32

Section 2- Behavioral explanations

.........................................................34

Introduction

.............................................................................................34

I- Definitions

.............................................................................................35

I-1\The sentiment's notion

...........................................................................36

I-2\ Hot IPO market's phenomenon

..................................................................37

I-3\ Investors typology

...........................................................................40

II- Literature review of behavioral explanations

................................................42

II-1\ Informational cascades

...........................................................................43

II-2\ The prospect theory

...........................................................................43

II-3\ Investor sentiment by Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh

(2004) ..............................45

II-4\ The use of Grey Market Data

..................................................................47

II-5\ The use of market conditions to value investor's

sentiment ..............................49

II-6\ Discount on closed-end funds as proxy for investor

sentiment ......................51

II-7\ Other proxies and empirical results

.........................................................52

Section 3- The model and empirical

implications ................................................55

Introduction

.............................................................................................55

I- The model and explanatory variables

.........................................................57

I-1\ The model

....................................................................................57

I-2\ The explanatory variables

..................................................................58

I-2-1\ Informational Asymmetry Theory

.........................................................58

I-2-2\ Theory asserting informational symmetry and IPO market

efficiency .............60

I-2-3\ Investor sentiment and Behavioral approach

................................................61

II- Data Description

....................................................................................62

III- Empirical implications and analysis

.........................................................70

CONCLUSION

....................................................................................77

References

.............................................................................................82

List of tables

Table 1. Average first day returns of some studies

................................................14

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of the Full Sample

................................................65

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of Firms with Low Underpricing

..............................67

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics of Firms with High

Underpricing ..............................68

Table 5. Average First-day Returns Categorized by Underwriter

prestige, Share Overhang, R&D Intensity, VC Backing, Age, Assets, Sales,

Firm profitability, Industry, Bargaining Power, Individual Investors' sentiment

and Time ................................................69

Table 6. Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results (with

Bullish proportion as investors' sentiment measure)

....................................................................................71

Table 7. Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results (with

Bullish Bearish Spread as investors' sentiment measure)

..................................................................72

Table 8. Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results

.......................................76

Abstract

U

nderpricing phenomenon has intrigued academics and

practitioners over the past three decades, and has generated considerable

research trying to clarify and to understand this short run puzzle: asymmetric

information theories, IPO market efficiency theories and behavioral and

sentiment approach. In this study, I regroup in the same model the most

important explanations advanced earlier to determine which of these

explanations characterizes best the data in the context of a unified framework,

with a contribution in the behavioral approach. I use a direct measure of

investors' sentiment obtained from the survey data of AAII and II, and I

distinguish between the sentiments of the two types of investors: individual

and institutional investors.

Sentiment is a primary driver of underpricing and a relevant

explanation to this anomaly. Moreover, individual investors are those driving

the first day closing prices and are more conducting the short run IPO puzzle

than the institutional investors.

INTRODUCTION

G

oing public constitutes a real driver for the development of a

company, enabling it to increase its equity capital and to overcome the

constraint that its founders are no longer able to provide the capital needed

for its expansion, and enabling it to diversify its sources of financing

without the need for debt. It is also a way to provide liquidity by creating an

opportunity to convert all or some founders and shareholders' wealth into cash

immediately or at a future date. Going public is also an opportunity to clarify

the company's business and strategy and to think about the company's future

growth. Not forgetting the role of going public and being listed in enhancing

the company's credibility and strengthening its image and reputation. When a

company decides to go public, shares offered in the stock market should be

correctly and truly valued. Issuers should also time the Initial Public

Offering to coincide with a favourable period (Hot market) to succeed their

first introduction in the market. But the question is, if the issuing firm's

managers are shrewd enough to value the company's shares and to choose a hot

market period, why underpricing is a persistent anomaly characterizing the IPO

market and why so much money is leaving on the IPO table?

Stoll and Curley (1970), Logue (1973), Reilly (1973) and

Ibbotson (1975), are the first who documented that when companies go public,

the first day closing price is systematically higher than the issue price at

which the public offering was introduced in the market. They are the first who

documented the first day underpricing phenomenon. And Ibbotson (1975) is the

first who offered a list of possible explanations for underpricing, many of

which were formally explored by other authors in later work.

The underpricing phenomenon has inspired a large theoretical

literature over decades trying to give a relevant and a convincing explanation

to this first day anomaly. It has intrigued academics and practitioners over

the past three decades and has generated considerable research trying to

clarify and to understand this phenomenon. The first explanations that were

advanced are based on the informational asymmetry between the key parties of an

IPO: issuing firm, underwriter and investors. These theories have been very

popular among academics and practitioners for decades and have been considered

as the most relevant and convincing explanation to the short run IPO anomaly.

However, other theories have been introduced asserting the informational

transparency and lucidity and the IPO market efficiency, since the first

theories based on asymmetric information are unlikely to give a relevant

explanation to the surprisingly and severe level of underpricing of 63.5%

reached in 1999 and 2000. This severe level of the internet boom years exceeded

any level previously seen. Researches are continuing, and it is fair to say

that this anomaly is not satisfactorily resolved. It is still a puzzle, since

nor the informational asymmetry theories neither the IPO market efficiency

theories are likely to give a convincing and a reliable explanation to this

short run IPO phenomenon.

Many researchers come to the conclusion that IPO future

researches should turn to behavioral approach and sentiment notion. Research

effort should focus more on behavioral explanations to clarify and to explain

the short run IPO behaviour and the underpricing anomaly: a new path trying to

understand and to explain this persistent anomaly. Turning to behavioral

explanations seems to be the most promising area of research to understand the

short run IPO behaviour.

We can say that the underpricing anomaly may be the most

controversial area of IPO research. Research effort has provided numerous

analytical advances and empirical insights, but underpricing is not yet

explained and the research effort is continuing.

In this thesis, I answer these two main problematics:

Ø What are the most relevant and reliable

explanations to the underpricing anomaly from the long list of explanations

advanced?

Ø If we rely on behavioral explanations based on

investors' sentiment to explain this phenomenon, what type of investors is more

conducting the underpricing phenomenon and the first day returns?

To answer these two main questions, I present in a first

section the phenomenon and its persistence in time, for all the countries and

for all the industries. I present the two main categories of explanations:

informational asymmetry and theories asserting the informational transparency

and the IPO market efficiency. I summarize the most important findings and

results of researchers that have considered these theories in their studies. In

a second section, I present the most important studies and papers that have

considered the sentiment explanation and the investors' behaviour as the most

convincing and relevant driver and determinant of IPO underpricing. In this

section, I give an idea about the application of the behavioral and sentiment

approach to clarify and to understand the IPO patterns by numerous researchers

and I shed light on the importance of the sentiment investors in the IPO

market.

Finally, in the third section, I regroup the most important

explanations that have been advanced in the same model to determine which of

these explanations characterizes best a sample of 217 U.S IPOs for 2006 and

2007. In the context of a unified framework and model, I present the three

theories: asymmetric, symmetric and behavioral approach.

For the behavioral approach, I use direct measures of

sentiment obtained from the survey data of American Association of

Individual Investors and Investors Intelligence. I distinguish

between the sentiments of the two types of investors: individual and

institutional investors, to answer the second question.

The main result is that sentiment is a primary driver of

underpricing and a relevant explanation to this short run anomaly. Moreover,

individual investors are those driving the first day closing prices and are

more conducting the short run IPO puzzle than the institutional investors.

Section 1- Short run IPO anomaly and traditional

explanations

Introduction:

The underpricing is a short run anomaly

characterizing the IPO market. This phenomenon has inspired a large theoretical

literature over decades trying to give a relevant and a convincing explanation

to this first day phenomenon. Underpricing anomaly has intrigued academics and

practitioners over the past three decades and has generated considerable

research aimed at explaining the apparent incongruities with rational asset

pricing. While this research effort has provided numerous analytical advances

and empirical insights and a large list of explanations were presented, it is

fair to say that this anomaly is not satisfactorily resolved. It is still a

puzzle sparking much academic attention until now and requiring other

explanations and much considerable research effort.

In this first section, I begin in the first paragraph by a

definition of the underpricing anomaly and an illustration of its persistence

over the time, all over the world and for all the industries, an order to have

a complete idea about this phenomenon. I summarizing in a second paragraph the

most important results and findings reached by the researchers that have been

interested in this field and have been interested in explaining the short run

IPO puzzle. These findings can be classified in two main categories:

Ø Explanations based on informational asymmetry between

the key parties which have been considered the most convincing explanations for

decades by a large number of researchers.

Ø And theories asserting the informational transparency

and lucidity and asserting the IPO market efficiency.

I- Underpricing anomaly: a persistent phenomenon that

characterizes IPO market

I-1\ Underpricing definition:

Before going in details, presenting the

explanations advanced for the short run IPO anomaly, it is logical to begin by

a definition of this notion of «underpricing» to understand this

short run phenomenon:

Early writers that have been interested in IPO market, notably

Stoll and Curley (1970), Logue (1973), Reilly (1973) and Ibbotson (1975), are

the first who documented that when companies go public, the price of shares

they sell tends to jump substantially on the first day of trading. The first

day closing price is systematically higher than the issue price at which the

public offering was introduced in the market. Consequently, IPOs exhibit

positive first day returns on average with no exception to the industry to

which the IPO belongs, to the country and to the period and date of going

public. That has been the first and the most important observation in the IPO

market.

From an issuer's point of view, this phenomenon is usually

called underpricing, as it describes the additional amount of money which could

have been raised by the issuer if the offer price had been set at an

appropriate level. Indeed, if the issuer had been set a higher offer price for

his offering shares, the issue price could have been easily accepted by the

investors interested in purchasing the IPO shares, since a run up is observed

on the first day of trading. The trading begins by the offer price which is

less than the apparent maximum price achievable at the end of the first trading

day. In a way it is an amount of money left on the IPO table from the issuers'

point of view. Therefore, underpricing is an expression used to describe the

issuer point of view, as he thinks that he has not correctly valued the IPO

shares, he underpriced the real value of the shares of his company.

Underpricing is estimated as the percentage difference between

the price at which the shares subsequently trade in the market (the first day

closing price) and the price at which the IPO shares were sold to investors

(the offer price or the issue price) and at which the offering was introduced.

Underpricing is suggesting that firms which go public leave considerable

amounts of money on the table. The amount of money left on the table is defined

as the difference between the closing price on the first day and the offer

price, multiplied by the number of shares sold. In the words of Jay Ritter,

this is the first-day profit received by investors who were allocated shares at

the offer price. It represents a wealth transfer from the shareholders of the

issuing firm to these investors. So, underpricing is a loss, a cost for the

issuers that they want to minimize and a profit for the first investors that

purchase and acquire the IPO shares.

I-2\ A persistent anomaly in time:

In the United States, at the end of

the first day of trading, the shares traded on average at 18.9% above the offer

price at which the company sold them (1990-2007). Underpricing has averaged

21.2% in the 1960s, 9% in the 1970s, and increasing from 7.8% in the 1980s to

14.4% in the 1990s and to a surprisingly and severe underpricing of 63.5% that

exceeded any level previously seen in 1999 and 2000 (reflecting the internet

boom years) before falling to 14% in 2001, averaged 11.8% from 2002 to 2006

before rising to 14% in 2007. These are the average levels of underpricing

observed in the United States IPO market. When we observe these different

levels and percentages of underpricing, we can say that underpricing fluctuates

so much and its level changes over time, but it is persistent over time. This

anomaly is always observed in the IPO market, whatever the industry to which

the offering belongs and whatever the period of going public. The level changes

but this anomaly is persistent.

In dollar terms, IPO firms appear to leave many billions

«on the table» every year in the U.S. IPO market alone. But the

highest amount is in 1999 and 2000, period of internet bubble, this amount of

money left on the table at IPO market has reached 66.63 billion dollars, an

amount that exceeded any level previously seen. It is the period of internet

bubble that attracted the attention of much research effort. Ritter documents

that in 1999 and 2000 only, 803 companies went public in the United States,

raising about $123 billion, and leaving about $65 billion on the table in the

form of initial returns. Loughran and Ritter (2004)1 explain

low-frequency movements in underpricing (or first-day returns) that occur less

often than hot and cold issue markets. On a data for IPOs over 1980-2003, they

find that IPO underpricing doubled from 7% during 1980-1989 to almost 15%

during 1990-1998 before reverting to 12% during the post-bubble period of 2001-

2003, there are some level differences over time but underpricing is

persistent.

1 Loughran and Ritter (2004): «Why Has IPO

Underpricing Changed Over Time?».

I-3\ A persistent anomaly in all countries:

Many researchers have been concentrated in

studying the persistence of underpricing anomaly internationally. The

underpricing phenomenon of Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) has been widely

studied across different stock markets around the world and it is a persistent

phenomenon all over the world.

Loughran, Ritter and Rydqvist (1994)2 documented

that the underpricing anomaly exists in all IPO markets. They collected data

for 45 countries for different periods and found that underpricing is

persistent for all the IPO markets with no exceptions but surely with different

levels.

A comparative study by Jenkinson (1990) examines the

performance of IPOs in Japan as well as IPOs in the U.S. and the U.K., and

concludes that IPOs in these countries are systematically priced at a discount

relative to their subsequent trading price. In the U.S. the discount is around

10% while in the U.K., it is around 7%. But when we see the next figures

presented by Jay Ritter and that represent the underpricing average in 2008 for

many countries, we can see that the level of underpricing has been increased in

comparison to the earlier results that were presented by many researchers.

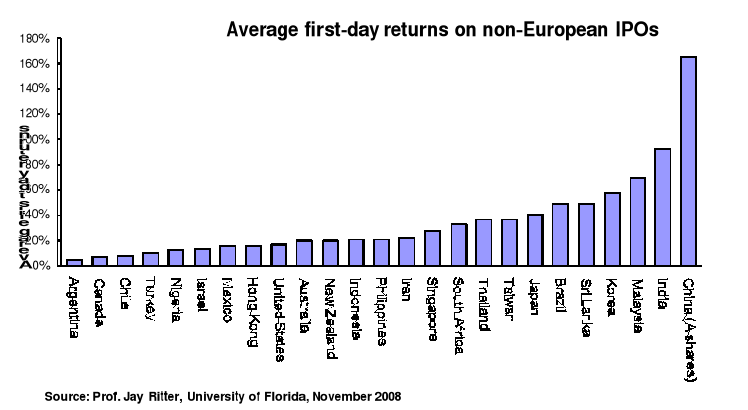

Figure 1- Underpricing on non-European IPOs (2008)

2 Loughran, Ritter and Rydqvist (1994):

«Initial Public Offerings: international insights».

Figure 2- Underpricing on European IPOs (2008)

Loughran et al. (1994) provide also a comprehensive survey of

companies going public in 25 countries and find that underpricing is a

persistent phenomenon. Ritter (2003) reports the extent of underpricing in 38

countries and finds the same results.

Table 1. Average first day returns of some studies

3

|

Country

|

Sample size

|

Time period

|

Avg first-day return %

|

|

Australia

|

381

|

1976-1995

|

12.1

|

|

Brazil

|

62

|

1979-1990

|

78.5

|

|

Canada

|

500

|

1971-1999

|

6.3

|

|

Indonesia

|

106

|

1989-1994

|

15.1

|

|

Mexico

|

37

|

1987-1990

|

33.0

|

|

Norway

|

68

|

1984-1996

|

12.5

|

|

Taiwan

|

293

|

1986-1998

|

31.1

|

|

UK

|

3.042

|

1959-2000

|

17.5

|

|

US

|

14.76

|

1960-2000

|

18.4

|

3 This table presents the results of some different

studies that were advanced. It is a demonstration of the persistence of IPO

underpricing for different countries regardless the period of the study, to

insist on the fact that this persistence is not only due to the period of IPOs.

Regardless the period, underpricing phenomenon exists for all countries.

I-4\ A persistent anomaly in all industries:

Underpricing is also persistent for all the

industries: automobile, banks, chemicals, construction, financial services,

food and beverages, industrial, machinery, media, pharmaceutical and health,

software, technology, telecommunications, transport and logistics ... Every

firm, which decides to go public, faces the phenomenon of underpricing, the

price of shares the firm sells tends to jump substantially on the first day of

trading regardless its field of activity. Underpricing is persistent for all

the firms no exception of the activity to which the firm belongs.

Oehler, Rummer, and N. Smith (2005) in their article «IPO

Pricing and the Relative Importance of Investor Sentiment, Evidence from

Germany», for a sample of 410 German firms from 1997 to 2001, they

classify the issuing companies by field of activity. When observing the number

of companies going public and the number of companies having a negative first

returns, we can say that most of companies going public have a positive first

day return and then their shares are underpriced regardless the field of

activity and regardless the industry they are belonging to.

II- Theoretical explanations of short run underpricing:

A literature review

The research effort aimed at explaining the

short run anomaly of the IPO market has provided numerous analytical advances

and empirical insights, and a large list of explanations has been offered.

Ibbotson (1975) is the first who offered a list of possible

explanations for underpricing, many of which were formally explored by other

authors in later work.

The list of explanations that were advanced to clarify and to

understand the underpricing anomaly and to resolve this short run puzzle of the

IPO market is long. The considerable research effort in the field of Initial

Public Offerings market has resulted in many explanations and the list can not

be exhaustive. In this paragraph, I summarize the most important researches and

findings and I classify the different theories and explanations advanced in two

main categories:

Ø Explanations related to the asymmetric information

theory that have been popular among academics and have been considered the most

convincing explanations for decades by a great number of researchers, and

Ø Explanations asserting the symmetric information.

II-1\ Asymmetric information:

The key parties to an IPO transaction are the

issuing firm, the bank underwriting and marketing the deal, and investors.

Asymmetric information models assume that one of these parties knows more than

the others.

II-1-1\ The issuer is more informed than the investors:

Welch (1989) and others assume that the issuer is better

informed about its true value.

* The theory of signalling; Firm quality:

The high quality issuers may attempt to signal their quality

and their true value, and to distinguish themselves from the pool of low

quality issuers, they voluntarily sell their shares at a lower price than the

market beliefs. They leave deliberately money on the IPO table to deter lower

quality issuers from imitating, and to demonstrate that they are high quality

by throwing money. Investors who are less informed about the issue quality and

about its true value will be incited to buy the shares since the price is low

and because they begin to believe on the high quality of the issuer. And the

issuers with some patience can recoup the amount of money left on the table by

future issuing activity. There are some issuers who have the intention to

conduct future equity issues at a later date on better terms (Seasoned Equity

Offerings SEO) (Welch 1989) or they look for favourable market responses to

future dividend announcements (Allen and Faulhaber 1989).

Michaely and Shaw (1994) argue that some issuers voluntarily

desire to leave money on the table in order to create, in the words of

Ibbotson 1975 «a good taste in investors' mouths» as a signal of high

quality, allowing issuers to have more successful Seasoned Equity Offerings in

the future. But, surprisingly, they find that the hypothesized relation between

initial returns and subsequent seasoned new issues is not present. There is no

relation between underpricing and Seasoned Equity Offerings. So, we can say

that the explanation of underpricing based on creating a good taste in

investors' mouths in order to have the investors' confidence in the future and

to conduct future equity issues on better terms and then recouping the amount

of money left on the IPO table, is not relevant and it is not convincing.

Jegadeesh, Weinstein, and Welch (1993), using data on IPOs

completed between 1980 and 1986, find that the likelihood of issuing seasoned

equity and the size of seasoned equity issues increase in IPO underpricing, as

expected. However, they note that these statistically significant relations are

relatively weak economically. But, Michaely and Shaw (1994) refute completely

the existence of this relation between underpricing and SEO.

Guo, Lev and Shi (2006) 4, using a sample of 6010

US IPOs from 1980 to 1995, find that R&D expenditures (using the ratio of

R&D expenditures to sales or to expected market value for the last fiscal

year before IPO as a measure) are the best proxy to informational asymmetry

about the issuer quality and find a positive and statistically significant

relation between the firm quality and underpricing. R&D expenditures are

the intangible investment most extensively researched in economics, accounting

and finance, they have to be disclosed in the corporate financial reports.

R&D contributes to informational asymmetry such as R&D intensive firms

are often undervalued by investors. That is why R&D intensive issuers can

not set a high offer price for their IPOs. Besides, they are more willing to

forgo money on the table at IPO than are no R&D issuers, because they

expect to recoup money left on the table by subsequent issues of seasoned

stocks when the market realizes over time the positive outcomes of their

R&D (in the words of the authors), because as I presented earlier some

studies find no relation between underpricing and SEO.

Guo, Lev and Shi (2006) introduce another measure of firm

quality in their model, the Share Overhang Ratio (the ratio of retained shares

by insiders to the number of shares issued). They find a positive and

statistically significant relation between firm quality and underpricing: the

percentage ownership retained by insiders serves as a signal for firm quality.

Also, Grinblatt and Hwang (1989) report a positive association between the

degree of underpricing and the level of insiders' ownership. For high overhang

ratio and so for high quality issues, the issue price is lower a mean to

demonstrate their quality and a higher level of underpricing is observed:

higher quality firms underprice more than do those of lower quality.

In their article «Why Has IPO Underpricing Changed Over

Time?», Loughran and Ritter (2004) use many proxies for the firm

quality:

4 Guo, R., B. Lev, and C. Shi (2006):

«Explaining the Short- and Long-Term IPO Anomalies in the US by

R&D».

Share overhang which is the ratio of retained shares to the

public float (the number of shares issued) and the Venture Capital a dummy

variable which takes a value of one (zero otherwise) if the IPO is backed by

venture capital. They find a positive and statistically significant relation

between the firm quality and underpricing using the share overhang ratio, but a

statistically insignificant relation using the venture capital as a proxy to

firm quality. The presence of venture capitalists in the IPO firm is expected

to signal issue quality, since their presence reduces the perceived uncertainty

over firm value. Venture capitalists have expertise in particular industries

and they are expected to make superior investments relative to other investors.

In essence, venture capitalists certify the quality of an IPO and their

presence signals that asymmetric information is relatively low for the issue

and that the issuing firm quality is high and hence leads to a higher issue

pricing and to a lower degree of underpricing (Megginson and Weiss, 1991). But

in this article, this variable is found insignificant. The same result of

insignificance using the venture capital backing as a signal of firm quality is

found by Guo, Lev and Shi (2006). A question is then can be asked: Is Venture

Capital backing really a signal of firm quality and an explanatory variable

that can be introduced in the models?

Ben Dov (2003) looks at the level of institutional ownership

shortly after the IPO and finds that high institutional ownership (a signal of

firm quality and a proxy for information asymmetry) forecasts higher returns in

hot markets.

In the same way of informational asymmetry and firm quality,

we can talk about the underwriter reputation (Booth and Smith (1986), Carter

and Manaster (1990), Michaely and Shaw (1994)). Some issuers use the

underwriter reputation as a signal of high quality and want to hire a

prestigious underwriter, since by agreeing to be associated with an offering,

prestigious intermediaries «certify» the quality of the issue. When

an issuer chooses a prestigious underwriter for the book-building mechanism, he

sets a low offer price conducting a high underpricing on one hand, as

compensation to the underwriter and on the other hand, he is sure about full

subscription. He is concerned by quantity rather than price, and a lower

offering price increases the probability of full subscription. It also

increases the positive news coverage and the investors' interest in future

equity offerings, if issuers have the intention to conduct Seasoned Equity

Offerings in later date to recoup the money left on the table. 5

5 All are explanations advanced by researchers to

the underpricing anomaly when issuers choose to hire prestigious underwriters.

Because, logically, hiring a prestigious underwriter is a signal of high

quality and issuers should require high offer prices for their high quality

issues.

This intention of Seasoned Equity Offerings can explain the

mystery that issuers seem to be happy and not upset when leaving money on the

table, they are certain to recoup this money in later date. 6

This explanation of underwriter reputation can take many

senses and will be discussed later in other theories.

II-1-2\ The investors are the most informed:

We are in the case of investors that are more informed than

the other parties about the demand, the price they are willing to pay to

acquire the IPO stocks, ...

* Information Revelation Theories:

To reduce this informational asymmetry, issuers tend to hire

underwriters and to use a «Bookbuilding mechanism». This common

practice of Bookbuilding consists on setting a preliminary offer price range by

the issuing firm, then the underwriter will take the role of trying to collect

private information from investors about the offering which is called

«indications of interest» such as their demand, the price they are

willing to pay to acquire the IPO shares... The bookbuilding mechanism allows

underwriters to extract this private information. During pre-selling period,

the underwriter tries to gauge demand and to have an idea about the price that

potential investors are willing to pay, these indications are then used in

setting the final offer price. If there is strong demand and the investors are

willing to pay a higher price to obtain the IPO stocks, the underwriter will

set a higher offer price and vice-versa.

But, Ritter and Welch (2002) add that if potential investors

know that showing a willingness to pay a high price will result in a higher

offer price, these investors must be offered something in return. They have to

be rewarded for communicating favourable information. Otherwise, if these

investors are offered nothing in return and the issuing firm will go public

with a higher offer price, investors are dissuaded and they will not reveal

their intentions and may even try to reveal wrong information to bias the

underwriter's decision.

6 There is a debate concerning the correlation

between underpricing and SEO, many researchers use the SEO as an explanation

for not requiring high issue prices for their offerings and others refute this

explanation and the relation between SEO and underpricing.

So, to induce investors to truthfully reveal that they want to

purchase shares at a high price, underwriters must offer them some combination

of more IPO allocations and underpricing when they indicate a willingness to

purchase shares at a high price : Benveniste and Spindt (1989), Benveniste and

Wilhelm (1990), and Spatt and Srivastava (1991).

Lee, Taylor, and Walter (1999) and Cornelli and Goldreich

(2001) show that informed investors request more, and preferentially receive

more allocations.

For the issuer, underpricing is on one hand compensation to

the underwriter: Baron (1982) has the same theory which is based on the fact

that issuers are less informed than underwriters, they delegate the pricing

decision to underwriters who possess superior information regarding the demand

for the IPOs, and to induce the underwriter to requisite effort to market

shares, it is optimal that issuer lets some underpricing because he can not

monitor the underwriter without cost. However, we should point out the findings

of Muscarella and Vetsuypens (1989) that when underwriters themselves go public

and then there is no monitoring cost, their offerings are also underpriced. So

underpricing is a necessary cost of going public and not a monitoring cost as

advanced by Baron.

On the other hand, underpricing is compensation to investors

to truthfully reveal their willingness to purchase the IPO shares and with a

higher price.

But we should also mention the fact that underwriters should

not underprice too much to not lose business from issuers. Nanda and Yun (1997)

find that high levels of underpricing lead to a decrease in the lead

underwriter's own stock market value, whereas moderate levels of underpricing

are associated with an increase in stock market value.

In a similar sense, Dunbar (2000) finds that banks

subsequently lose IPO market share if they either underprice or overprice too

much.

As a conclusion for the information revelation theory, we can

say that underpricing can be reduced by reducing the informational asymmetry

between the IPO parties.

And as Ritter and Welch (2002) note, if underwriters used

their discretion to bundle IPOs, problems caused by asymmetric information

could be nearly eliminated.

Underwriters, are intermediaries between issuer and investors,

they advise the issuer on pricing the issue, both at the time of issuing a

preliminary prospectus that includes a file price range, and at the pricing

meeting when the final offer price is set. In the bookbuilding period, they try

to collect the investors' private information which can help in setting the

price and even the volume of IPO shares. Their role is very important in

reducing the information asymmetry by transmitting the investors' private

information to issuers. So, the revelation information theory is based on the

work of underwriters.

I presented in the previous paragraph that underpricing is

positively associated with underwriter reputation. For example, consistent with

evidence from the 1990s (Beatty and Welch (1996)), Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh

(2004) predict that underpricing increases in underwriter prestige, but that

this relation depends on the state of the IPO market.

Also, Benveniste, Ljungqvist, Wilhelm and Yu (2003) find a

positive relation between underpricing and underwriter prestige in the

1999-2000 hot market.

First, we should present the measures used of underwriter

reputation: Carter and Manaster (1990) provide a ranking of underwriters based

on their position in the `tombstone' advertisements in the financial press that

follow the completion of an IPO. This ranking, since updated by Jay Ritter, is

much used in the empirical IPO literature, it is a discrete underwriter

reputation measure ranging from 0 to 9, where a 9 (0) represents the most

(least) prestigious underwriter.

Megginson and Weiss (1991) measure underwriters' reputation

instead by their market share, and this approach too is widely used.

The fact of using a prestigious underwriter in the

bookbuilding process has an impact on signalling the high quality of the

issuing company as I said earlier, but it has also a great impact on the

information revelation, since prestigious underwriter is a source of confidence

to investors. The prestigious underwriter has a great ability and power to make

investors reveal their private information.

Many explanations were presented to the positive relation:

when an issuer decides to hire a prestigious underwriter, he is sure about a

full subscription, he is concerned by quantity rather than price, and by

setting a low offer price, he tries to increase the probability of full

subscription. There are some other issuers who are concerned by their firm

quality and by hiring a prestigious underwriter, they tend to demonstrate their

high quality and they set a low offer price as a signal of quality and of the

real value of the company. From the point of informational revelation theory,

underpricing and underwriter reputation are positively related because

underpricing is used as compensation to the underwriter (Baron 1982).

In Loughran and Ritter (2004) model, top-tier underwriters are

associated with more underpricing in the 1990s, and especially in the bubble

period.

Loughran and Ritter (2003) argue that prestigious banks have

begun to underprice IPOs strategically, in an effort to enrich themselves or

their investment clients. Another explanation is that top banks have lowered

their criteria for selecting IPOs to underwrite, resulting in a higher average

risk profile (and so higher underpricing) for their IPOs.

But the relation between underwriter reputation and

underpricing is not systematically positive and it is empirically mixed, there

are some researchers who find that the correlation between underpricing and

underwriter reputation is negative: when an issuer hires a prestigious

underwriter, he can set a higher offer price and then lower underpricing will

be observed. For example, Carter and Manaster (1990), and Carter Dark and Singh

(1998) find that more prestigious underwriters are associated with lower

underpricing.

There are also some researchers who have introduced the

underwriter reputation variable in their models and find that it is

statistically insignificant as in Guo, Lev and Shi article (2006). These

authors have introduced the underwriter reputation as an explanatory variable

to explain underpricing and find that it is statistically insignificant.

In practice, results are not very sensitive to the choice of

underwriter reputation measure, but they are highly sensitive to the period

studied.

* Winner's Curse:

Rock (1986) assumes that some investors are more informed than

are other investors in general, the issue firm, and its underwriter. There is

an imbalance of information between the potential investors themselves. These

better informed investors bid only for attractively priced IPOs. In the case of

unattractive offering, the better informed investors will not purchase the

shares and the uninformed investors will have all shares they have bid for

because they bid indiscriminately. But, these uninformed investors are unable

to absorb all the shares offered, that is why underpricing is necessary to

incite informed investors to bid for this offering's shares even if they think

it is unattractive. The lower offer price will incite them to try to have the

offering's shares. This underpricing is necessary also to not result in a

negative return for this offering for the uninformed investors, whose capital

is needed even for an attractive offering. They must be protected in IPO market

to not lose their capital and their participation because in the case of

attractive offerings, informed investors are also unwilling to absorb all the

shares offered and their demand is insufficient. The uninformed investors

should not fear the IPO market, positive returns are required to protect them

and to ensure a continued participation in IPO market.

In the spirit of Rock (1986), Chowdry and Nanda (1996) develop

a model in which price support is used as a complement to underpricing to

reduce the losses supported by uninformed investors and induce them to

participate in the IPO.

In conclusion for the theory of winner's curse of Rock 1986,

which is an application of Akerlof's (1970) lemons problem, underpricing is

necessary to not lose the capital of uninformed investors and to incite

informed investors to take part of an offering allocation even if it is

unattractive. Pricing too high might induce investors and issuers to fear a

winner's curse.

In the same sense of inciting informed investors to

participate in an unattractive offering, Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh (2001)

find and explain underpricing by the fact that noise traders cannot absorb the

entire IPO because they are wealth constrained. To induce rational investors to

participate in the offering, issuers must set the IPO price below the price

noise traders are ready to pay, to induce underpricing and to make the offering

attractive for the rational investors. These better informed investors can sell

the shares to the irrational investors in the aftermarket and make a profit.

Rock's (1986) winner's curse model turns on information

heterogeneity among investors. Michaely and Shaw (1994) argue that as this

heterogeneity goes to zero, the winner's curse disappears and with it the

reason to underprice.

Tore Leite (2007) in his article «Adverse selection,

public information and underpricing in IPOs» finds that favourable public

information (such as high market returns) reduce the winner's curse problem.

And this induces the issuer to price the issue more conservatively in order to

increase its success probability. The author finds a positive relation between

public information and underpricing.

* Agency conflicts: The agency problems between the

underwriter and the issuing firm.

Underpricing represents a wealth transfer from the IPO company

to investors. These investors compete for allocations of underpriced stock,

they can even try to collude with the underwriter by offering side-payments if

they have underpriced stocks. Such side-payments could take the form of

excessive trading commissions paid on unrelated transactions, or investment

bankers might allocate underpriced stock to executives at companies in the hope

of winning their future investment banking business, a practice known as

«spinning». So the underwriters, seeking for their own interests have

an incentive to underprice IPOs if they receive commission business in return

for leaving money on the table, they will try to underprice the issuer's stock

by not revealing the truthfully information obtained from potential investors

...

The underwriter will use a sub-optimal effort. He will use his

informational advantage over issuing companies to increase his benefit and he

will not do his mission perfectly. The underwriters are given discretion in

share allocation. This discretion will not automatically be used in the best

interests of the issuing firm, and they can also underprice more than necessary

and then allocate these shares to favoured buy-side clients.

In the post-bubble period, increased regulatory scrutiny

reduced spinning dramatically. This is one of several explanations why

underpricing dropped back to an average of 12%.

As a conclusion, we can say that issuing firms who seek out

prestigious underwriters to advice, to look after the IPO process, to bear for

the risk of hot market crashing... can suffer from enormous problems if

conflict of interest problems are not controlled.

Baron and Holmström (1980) and Baron (1982) construct

screening models which focus on the underwriter's benefit from underpricing. In

a screening model, the uninformed party (issuer) offers a menu or schedule of

contracts, from which the informed party (underwriter) selects the one that is

optimal. The contract schedule is designed to optimize the uninformed party's

objective, which, given its informational disadvantage, will not be first-best

optimal. To induce optimal use of the underwriter's superior information about

investor demand, the issuer in Baron's model delegates the pricing decision to

the bank (the underwriter). Given its information, the underwriter self-selects

a contract from a menu of combinations of IPO prices and underwriting spreads.

If likely demand is low, he selects a high spread and a low price, and vice

versa if demand is high. But as we said earlier, underwriter can use this

delegation to increase his own benefit and to think about his individual

interest only. He can collude with the potential investors to the potential

detriment of the issuer.

This agency conflict can be mitigated in two ways:

Ø Issuers can monitor the investment bank's selling

effort and bargain hard over the price,

Ø or they can use contract design to realign the bank's

incentives by making its compensation an increasing function of the offer

price.

Ljungqvist and Wilhelm (2003) provide evidence consistent with

monitoring and bargaining in the U.S. in the second half of the 1990s. They

show that first-day returns are lower, the greater are the monitoring

incentives of the issuing firms' decision-makers.

Ljungqvist (2003) studies the role of underwriter compensation

in mitigating conflicts of interest between companies going public and their

investment bankers (their underwriters). Making the bank's compensation more

sensitive to the issuer's valuation should reduce agency conflicts and thus

underpricing. Consistent with this prediction, Ljungqvist shows that

contracting on higher commissions in a large sample of U.K. IPOs completed

between 1991 and 2002 leads to significantly lower initial returns, after

controlling for other influences on underpricing and a variety of endogeneity

concerns.

So, we can say that by making underwriter's compensation an

increasing function of the offer price or of the issuer's valuation, the agency

conflicts between underwriter and the issuing company could be mitigated.

Underpricing could even disappear if we consider the agency conflicts as the

primary driver and source of underpricing.

As a conclusion for the asymmetric

information theories, we can say that almost informational asymmetry theories

share the prediction that underpricing is positively related to the degree of

asymmetric information, and when asymmetric information uncertainty approaches

zero, underpricing disappears entirely.

II-2\ Symmetric information:

There are some theories and explanations

advanced by a great number of researchers that do not rely on asymmetric

information, this theory that has been very popular among academics and

practitioners for decades and that has been considered as the most relevant and

convincing explanation to the short run IPO anomaly. There are some researchers

that advanced other theories and they explain underpricing by other reasons,

asserting symmetric information between key IPO parties. As hypothesis, all the

key parties of an Initial Public Offering share the same information. We talk

about informational transparency and lucidity and about IPO market

efficiency.

II-2-1\ Risk premium:

Let's begin by the risk premium explanation. Because the hot

market can end prematurely, the sentiment demand may cease and then we face a

market crashing, carrying IPO stocks in inventory is risky.

Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh (2003) in their article: «Hot

market, investor sentiment and IPO pricing» argue that underpricing

emerges as fair compensation to the regulars for expected inventory losses

arising from the possibility that the hot market ends prematurely. If the

demand is small (in comparison to the issue offer), the issuer needs the

regular investor to hold inventory. So long as the hot market persists, the

regular investor sells this inventory to newly arriving sentiment investors,

but the problem arises if the hot market ceases and the regular investor is

then left with shares priced at the fundamental value (which is less than the

offer price).

The issuer underprices the stock to compensate the regular

investor for bearing the risk of an uncertain sentiment demand. It is a fair

payment for the regular's expected loss. It is a way of compensating the

regular investor for taking on the risk of hot market crashing.

However, Ritter and Welch (2002)7 refute this

explanation since they argue that if the underpricing is simply a compensation

for bearing a systematic or liquidity risk, why do second-day investors not

seem to require this premium, after all fundamental risk and liquidity

constraints are unlikely to be resolved within one day.

As a conclusion for the risk premium explanation based on

Ritter and Welch (2002) point of view, we can say that this explanation is

refuted and can not be considered as a relevant and a convincing explanation

for the underpricing anomaly.

II-2-2\ Characteristics of the Initial Public offering:

* Risk: Risk can reflect either technological or

valuation uncertainty.

Loughran and Ritter (2004) use many measures of risk: the

natural logarithm of the assets and the natural logarithm of the sales which

reflect the issuing firm size and then a risk related to valuation uncertainty,

internet and tech dummy variables which reflect technological uncertainty which

also induces a valuation uncertainty, and the natural logarithm of one plus the

age (years since the firm's founding date to the date of going public and the

date of introduction in IPO market) which reflect the age of the issuing firm.

For a sample including 5,990 US operating firm IPOs over 1980-2003, they find a

positive relation between risk and underpricing.

If the issuing firm is risky from the investors' point of

view, it can not be introduced in the market at a higher price because it will

not be accepted by these investors who are dissuaded about the risky IPO

shares. The offer price is set at a lower level to incite investors

7 Ritter and Welch (2002): «A review of IPO

activity, pricing, and allocations».

to purchase the IPO stocks even if they think it to be

risky.

The risk composition hypothesis, introduced by Ritter (1984),

assumes that riskier IPOs will be underpriced by more than less-risky IPOs.

Riskier firms set a low offer price to incite investors to participate in the

IPO market and to buy the IPO risky shares, and then the underpricing will be

higher. For example, young firms are riskier and the internet bubble period saw

a high proportion of young firms going public and a high percent of

underpricing, which can confirm the explanation of risk.

In the same direction of the risk, we can also talk about the

uncertainty level introduced by Beatty and Ritter (1986). They relate the level

of ex-ante uncertainty surrounding the intrinsic value of an IPO to the level

of underpricing. The higher the uncertainty level about the intrinsic value of

the IPO, the higher is the level of underpricing. It reflects the valuation

uncertainty.

Besides, Bartov, Mohanram and Seethamraju (2003) report that a

dummy variable for risky IPOs has no effect on the setting of the final offer

price, providing evidence for the argument that risk might not be that

important for the pricing of IPOs. So there is no correlation between risk and

underpricing. The notion of risk can not explain the setting of a lower offer

price and then the underpricing phenomenon. This important finding refutes the

prior researches and results about the suitability of the risk as an

explanation to the underpricing anomaly. Risk can not be considered as a

convincing explanation to the short run IPO anomaly since it has no effect on

the setting of a lower offer price, and then underpricing is not induced by

risk.

* Issue size: The issue size or offer size is the

number of shares introduced in IPO market and offered by the issuing company

for sale.

Cornelli, Goldreich and Ljungqvist (2004) argue that when the

issue size is large, the issue price should reflect the greater difficulty of

selling the shares in the aftermarket, and then the issue price should be

lower. They find a negative relation between the size and the offer price of

IPOs: a discount in the offer price by ëS with S the size of IPOs. When

the offer size is large, the offer price will be lower and so underpricing will

be higher. They find that the issue price should be negatively correlated with

the issue size, and it is a negative and statistically significant relation

between size and offer price, so we can talk about a positive and significant

relation between issue size and underpricing.

This relation between issue size and underpricing was studied

briefly in Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh (2003) article. Supposing VR

the market price of the IPO shares and VS the value sentiment

investors place on the IPO shares and so is the price these investors are

willing to pay for the IPO shares, the authors set VS as a function

of VR and Q which represents the total number of IPO shares (the

offer size), and the relation between VS and Q is negative. The

greater is the number of shares issued, the lower is the price that sentiment

investors are willing to pay, and the greater is underpricing: positive

relation between issue size and underpricing.

Besides, some researchers find a negative relation between the

issue size and underpricing. Guo, Lev and Shi (2006) introduce a different

issue size variable in their model (the natural logarithm of issue proceeds)

and find a negative relation between issue size and underpricing. They explain

this finding by the fact that sizable firms are generally less risky than those

making smaller issues, and they can bargain for a higher offer price conducting

a lower level of underpricing.

* Bargaining power:

Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh (2003) study the impact of

bargaining power on the first day return and so on underpricing. They use as a

proxy for bargaining power «the ownership structure». A firm with a

highly concentrated ownership, is reflecting a high incentive to bargain hard,

while an increased ownership fragmentation, and an increased frequency and size

of «friends and family» share allocations, make the issuing firm

decision-makers less motivated to bargain for a higher offer price .

Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh assume that the issuing firm's

ownership structure is such that â of the extracted surplus from the

investor sentiment is captured by the issuing firm and 1-â is

captured by a combination of the regular investor and the investment bank. For

a firm with highly concentrated ownership, they believe â will

be close to 1 reflecting the high incentive to bargain hard over the surplus,

while for a firm with dispersed ownership or other agency problems â will

be significantly smaller than 1.

An issue firm with a concentrated ownership and high

bargaining power requests a higher offer price and faces a lower underpricing.

Ljungqvist and Wilhelm (2003) show that companies with more concentrated

ownership at the time of the IPO suffer lower underpricing, consistent with the

findings of Ljungqvist, Nanda and Singh (2003).

And an issue firm characterized by ownership fragmentation and

so by lower bargaining power, can not bargain hard for a higher offer price.

The issue price will be set at a lower level and underpricing will be higher in

the first day of trading. Tim Loughran and Jay Ritter (2004) 8 also

use the ownership structure as a proxy for bargaining power and find that an

increased ownership fragmentation induces a decrease in the bargaining power of

the issuing firm, a lower offer price is presented inducing a higher level of

underpricing.

The greater the issuing firm's bargaining power relative to

the underwriter, the higher is the offer price and the lower is the first-day

return and vice-versa.

II-2-3\ Lawsuit avoidance: legal liability

Lawsuits are obviously costly, not only directly: damages,

legal fees, diversion of management time, etc, but also in terms of the

potential damage to their reputation capital. Litigation-prone investment banks

may lose the confidence of their regular investors, while issuers may face a

higher cost of capital in future capital issues.

The basic idea of lawsuits avoidance goes back at least to

Logue (1973) and Ibbotson (1975): companies deliberately sell their stocks at a

discount to reduce the likelihood of future lawsuits from shareholders

disappointed with the post-IPO performance of their shares.

Tinic (1988), Hughes and Thakor (1992) and Hensler (1995)

argue that issuers intentionally underprice to reduce their legal liability.

They assume that the probability of litigation increases with the offer price:

the more overpriced an issue, the more likely is a future lawsuit, and that the

solution is underpricing to avoid future lawsuits. Ritter and Welch (2002) give

a simple example for this: An offering that starts trading at 30$ that is

priced at 20$ is less likely to be sued than if it had been priced at 30$, if

only because it is more likely that at some point the aftermarket share price

will drop below 30$ than below 20$.

Tinic identifies a sample of 70 IPOs completed between 1923

and 1930 and compares their average underpricing to that of a sample of 134

IPOs completed between 1966 and 1971. As Tinic predicted, average underpricing

was lower before 1933 (year of securities enactment).

In spite of this, Drake and Vetsuypens (1993) find that

underpricing did not protect issuers firms from being sued, and sued IPOs had

higher and not lower underpricing.

8 Loughran and Ritter (2004) argue that this

argument has little support as an explanation for underpricing.

They study a sample of 93 IPO firms that were sued and compare

them to a sample of 93 IPOs that were not sued, matched on IPO year, offer

size, and underwriter prestige. Underpriced firms are sued more often than

overpriced firms. Then underpricing does not protect firms from being sued and

does not protect them from lawsuits and future legal liabilities.

They also show that average initial returns in the six years

after Tinic's sample period (1972-1977) were actually lower than

between 1923 and 1930 which refute his findings.

Ritter and Welch (2002) think that leaving money on the table

appears to be a cost-ineffective way of avoiding subsequent lawsuits. But the

most convincing evidence that legal liability is not the primary determinant of

underpricing is that countries in which U.S. litigative tendencies are not

present have similar levels of underpricing (Keloharju (1993)):

The risk of being sued is not economically significant in

Australia (Lee, Taylor, and Walter (1996)), Finland (Keloharju (1993)), Germany

(Ljungqvist (1997)), Japan (Beller, Terai, and Levine (1992)), Sweden (Rydqvist

(1994)), Switzerland (Kunz and Aggarwal (1994)), or the U.K. (Jenkinson

(1990)), all of which experience underpricing.

After all these findings which refute the suitability and the

relevance of lawsuit avoidance as an explanation to underpricing anomaly, we

can say that lawsuit avoidance can not be a primary determinant and driver of

underpricing, still, it is possible that lawsuit avoidance is a second-order

driver of IPO underpricing.

II-2-4\ Underpricing as a substitute of marketing

expenditures:

Habib and Ljungqvist (2001) argue that underpricing is a

substitute for costly marketing expenditures. Using a data set of IPOs from

1991 to 1995, Habib and Ljungqvist report that an extra dollar left on the

table reduces other marketing expenditures by a dollar. On the first sight,

underpricing seems to be just a substitute for marketing expenditures since

both have the same cost, but underpricing is much more interesting.

By going public and by underpricing and leaving money on the

IPO table, issuing firms can achieve a total coverage media and good news in

all media, which can be much more costly if the firm chooses to use publicity

and marketing expenditures, mainly because we can not forget the possibility of

recouping this money left on the IPO table if the firm has the intention to

conduct Seasoned Equity Offerings in the future. So, the issuing firm achieves

a large coverage media and an important publicity without spending anything,

since the money left on the IPO table will be recouped later. By underpricing,

the investors who bought the IPO shares have confidence in the issuing firm,

they are satisfied with the gains they retired from the IPO shares and from

underpricing in the first day of trading. Optimistic about the value of this

firm, these investors will easily accept the price the firm set for its

Seasoned Equity Offerings at a later date. Even if the price is higher than

necessary, they will accept it since they have confidence in this firm, and

then all the money left on the table can be recouped by conducting Seasoned

Equity Offerings in the future. 9

II-2-5\ Internet Bubble:

One popular related explanation for the high and severe

underpricing of 65% during the Internet bubble (1999-2000) for the U.S IPOs, a

peak never reached before in the U.S IPO market, is that underwriters could not

justify a higher offer price on Internet IPOs. Even if these firms have a high

potential of profitability in the recent future and they are operating in a new

but very promising field which will generate high returns later, the

underwriters can not justify this and propose a higher offer price. These firms

are seen as young and operating in a new field which means that their offerings

are risky and they propose risky shares. Proposing a higher offer price will

not be accepted by investors and will make them fear the offerings. The issuing

firms have to propose a low offer price to incite investors to participate in

the offerings even if they are thought to be risky. So, we can say on one hand,

the newly issuing Internet firms are very important and are operating in a very

promising field and then will generate high returns, but all this can not be

justified by their underwriters and they do not find the convincing arguments.

On the other hand, and since they are operating in a new field not very known

and they are very young firms without a history of returns, they are thought to

be risky. So, we are in the same explanation of risk due to valuation

uncertainty which was proved to be ineffective determinant and explanation for

the underpricing anomaly.

So to explain the severe level of underpricing during the

dot-com period, only the inability to justify a higher offer price can be

considered as a possible explanation, but the fact of young and so risky firms

can not be used as a relevant explanation.

9 As a support for IPO as a marketing event,

Chemmanur (1993) proposes that this publicity could generate additional

investor interest, and Demers and Lewellen (2003) suggest that the publicity

could generate additional product market revenue from greater brand

awareness.

II-2-6\ Price stabilization and partial adjustment:

Recent studies have also documented the impact of public

information. They find a positive link between the «market

conditions» prevailing at the time of an offering which represent public

information and its subsequent initial return. Favourable market conditions

predict higher underpricing and vice-versa. Derrien and Womack (2003)

show that the initial returns on IPOs in France in the 1992-1998 period were

predictable using the market returns in the three-month period preceding the

offerings. Using U.S. data, Loughran and Ritter (2002) and Lowry and Schwert

(2003) obtain similar results: the initial returns in the first day of trading

for IPOs are predictable using the market conditions prevailing at the time of

the IPOs or at a recent past. Favourable market conditions predict higher

initial returns and so higher underpricing, and critical market conditions

predict lower initial returns and lower underpricing, and for some IPOs

negative initial returns and overpricing.

Bradley and Jordan (2002) include the 1999 `hot issue' market

in their sample and find that more than 35% of initial returns can be predicted

using public information available at IPO date. However, Lowry and Schwert

(2003) find that the effect is economically small.

These favourable market conditions have an impact on noise

traders who will be ready to pay higher IPO prices. They are assumed to be

bullish at the time of the offering since they are very influenced by market

conditions: the more favourable market conditions are, the more favourable

noise traders' sentiment is and the higher the price that they are willing to

pay.

But the mystery and the question that arises automatically is,

why underwriters do not incorporate these favourable market conditions and this

favourable sentiment when pricing the IPO and propose a higher offer price

which reduces the underpricing anomaly and the money threw on the table? Why

market conditions and noise traders' sentiment are only partially incorporated

in IPO offer prices?

The underwriter is not only concerned with the IPO price at

the time of offering, but he is also concerned with the aftermarket behaviour

of IPO shares in the short run as well as on the long run. He is committed to

provide costly price support if the aftermarket share price falls below the IPO

price (the issue price) in the months following the offering. Even if the noise

traders are bullish at the time of offering, they can change their attitude in

the aftermarket.

And a sharp and rational underwriter with a reasonable

attitude should take this into consideration when pricing the IPO. Derrien

(2003) says that the IPO price results from a trade-off: a higher IPO price

increases underwriting fees, but also the expected cost of price support.

This induces the underwriter to set a conservative IPO price

with respect to the short-term aftermarket price of IPO shares. The underwriter

has to incorporate partially the market conditions when pricing IPO to not face

a higher cost of price support if the aftermarket price falls.

When setting the offer price, we can say that the underwriter

is constrained by the cost of price support if the aftermarket price of IPO

shares falls below the issue price (if he overpriced the IPO shares), but he is

also constrained by the lost of IPO market shares if he sets a very low issue

price to reduce the risk of support's price costs inducing very high

underpricing. In this sense, Booth and Smith (1986) claim that the

underwriter's role is to certify that IPO shares are not overpriced. Therefore,

an underwriter that underprices more than necessary the IPOs will lose market

shares on the IPO market and will lose the issuing firms' confidence, this is

confirmed empirically by Dunbar (2000), and an underwriter that overprices the

IPO shares will pay high costs of price support. Legal costs may also refrain

underwriters from blatantly overpricing new issues, even though investors'

demand is very large.

Aggarwal (2000) and Ellis, Michaely and O'Hara (2000) provide

evidence that underwriters intervene to stabilize the price of IPO stocks that

exhibit poor aftermarket performance. The underpricing is important to

stabilize the IPO prices to compensate the long run underperformance of the

issues.

Section 2- Behavioral explanations

Introduction:

Short run IPO anomaly may be the most

controversial area of IPO research. The research effort has provided numerous

analytical advances and empirical insights trying to explain the first day

price run up. Many explanations were introduced and studied, but all these

theories are unlikely to explain the persistent pattern of high initial returns

during the first trading day. It is fair to say that this anomaly is not

satisfactorily resolved and is still a puzzle.

Many researchers come to the conclusion that IPO future

researches should turn to behavioral approach and sentiment notion. Research

effort should focus more on behavioral explanations to clarify and to explain

the short run IPO behaviour, since nor the asymmetric theories neither the

explanations based on the informational symmetry are likely to give a relevant

and a reliable explanation to the underpricing anomaly, mainly after the

surprisingly and severe level of underpricing reached in 1999 and 2000, the

internet boom years. The explanations that have been advanced earlier are

unable to explain the severe percentage of underpricing observed in this

period, and turning to behavioral explanations seems to be a necessity to

resolve this short run IPO puzzle.

Ritter and Welch (2002), for example, advance clearly that

asymmetric information which has been the most convincing explanation for

decades, is not the primary driver of IPO phenomena and asymmetric information

models that have been popular among academics, have been overemphasized. Ritter

and Welch believe that future progress in the IPO literature will come from non

rational explanations.

This argument is supported by Ljungqvist (2004) who comes to

the conclusion that IPO researchers should focus on behavioral approaches to

explain why the extent of underpricing varies so much over time.

Future researches have to focus more on behavioral

explanations and turning to the behavioral approach describing the behaviour of

irrational investors and their sentiment seems to be a necessity since the

explanations and the theories that were advanced earlier are unlikely to

clarify and to explain the short run IPO puzzle, especially after the dot-com