|

MASTER'S THESIS

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Master Complémentaire Conjoint en Microfinance

(European Microfinance Programme)

Assessing the Viability of a Rural Microfinance Network:

The Case of FONGS FINRURAL

By Oniankitan Grégoire AGAÏ

Supervisor: Mr. Kurt MOORS

Assessor: Professor Marijke D'HAESE

Internship organization: Fédération des

Organisations Non Gouvernementales du Sénégal

Academic year 2011-12

MASTER'S THESIS

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of Master Complémentaire Conjoint en Microfinance

(European Microfinance Programme)

Assessing the Viability of a Rural Microfinance Network:

The Case of FONGS FINRURAL

By Oniankitan Grégoire AGAÏ

Supervisor: Mr. Kurt MOORS

Assessor: Professor Marijke D'HAESE

Internship organization: Fédération des

Organisations Non Gouvernementales du Sénégal

Academic year 2011-12

Dedication

This thesis is dedicated to:

my daughter Eyitayo Hillary Stella Achène

her grand brother Yamontè Donald

their mum, my spouse Yaba Fousséna

Sandrine-Ruth

my mother Rose

my father Dominique

Foreword

The present study was effectuated in conditions of MFIs

professionalization in West African countries. This region is peculiarly renown

as holding a relatively impressive number of savings and credit cooperatives

and unions. The current regulation in UMOA zone avoids the use of the term MFI.

Throughout this paper, the terms DFS, savings and credit cooperatives, savings

and credit mutuals, savings and savings associations will be used

interchangeably.

The findings, interpretations and conclusions uttered in this

thesis do not necessarily reflect the orientation of the Université

Libre de Bruxelles or the Fédération des Organisations Non

Gouvernementales du Sénégal.

Acknowledgments

Foremost, I thank God, the Divine Maker and the Almighty for

his mercy and for his love toward me. May his Name Thrice Holy be blessed and

glorified everywhere and forever.

I am grateful to the Commission Universitaire pour le

Développement (CUD) which provided me full scholarship to pursue this

programme. It was for me a great and special opportunity to meet and share with

various and diversified nationalities and intelligences.

In the same vein, I am grateful to Mr. Kurt Moors, my thesis

supervisor, who provided me all the advices and comments in order to perform

this work. I am grateful to him for providing me the Echos(c) tool of Incofin

for the social performance analysis.

I am also grateful to Mr. Axel de Ville with whom I had my

first temptations for identifying the topic and writing the first proposal and

bibliography. I thank him for orienting me in a good manner possible in order

to obtain good results.

I am fully indebted toward all my EMP teachers for providing

me insights on the microfinance field and for opening my mind on critical

issues in the industry and challenges for future.

I am sincerely grateful to all my managers for allowing me to

follow and complete this course. May each of them sees through this thesis the

product of their work.

I am grateful to SOS Faim for providing me the internship

within the FONGS. Particularly I thank François Cajot for his

solicitude.

I am grateful to the FONGS, my host institution for accepting

me and providing me useful information regarding the goals of this thesis.

Particularly, I am grateful to Habidine Sow, Aïcha Faye, and Masse Gnigue

with whom I spent marvellous moments in Thiès.

I cannot forget the camaraderie of all the EMP students with

whom I followed the programme. Particularly I wish to mention Li, Firog,

Muluneh, Luhana, Peter, Roopa, Charleine, Sonia (mi capo), Victoire (my twin in

Senegal), Marie, Davide (my class neighbour), Natalia, Tomas, Alicia,

Hervé, Pierre, Maxime, Selassie, Le, Marco, Patrick (the American),

Fatimata, Stephane, John, Gabrielle etc.....

I thank all my parents, relatives and friends who supported me

during my stay in Brussels.

How can I forget you Fousséna, Stella and Donald for

your sacrifice? I am fully aware that it was not easy; but if I have reached

the goal, it is mainly due to your love and your perpetual support. Thank you

for you love, your support and the sacrifice.

EXECUTIVE SUMARY

The present thesis endeavours to assess the viability of the

FONGS FINRURAL, a nascent network of 09 rural savings and credit cooperatives

in Senegal. More specifically it strives to measure first how the social and

financial performance and the governance vary among the network affiliated

organizations, and second to what extent all this aspects in each MFI could

affect the viability of the network.

For cause of data availability, the research was carried on 7

out of the 9 affiliated MFIs.

The methodology has consisted first in the exploitation of

financial reports, financial statements, business plans, manual of procedures,

minutes, reports and any kind of internal documents seeming useful and second

in visits at basic affiliated associations and client information.

Four data collection tools were used: the factsheet of

financial assessment devised by BRS and ADA, the ECHOS(c) tool of social

performance assessment of Incofin, version 2012, the aggregated index of

governance grid, and specific interview grids to each MFIs based on their

financial and social performance recorded and on their governance score as

well.

Financial data were collected over four years (2008-2011),

while social and governance data were a snapshot of the MFIs as of may-august

2012.

Different descriptive statistics were used for comparisons.

The coefficient of correlation rho of Spearman was used to make links between

financial performance, social performance and governance.

It comes out from the peer group analysis that the membership

of the entire seven MFIs, dominated by women (50%), is growing over years with

an average of 23% sharply higher than that of the country (8.7%). This trend

presents however some specificities pertaining to each MFI.

In the same vein, the network records an increase in savings

collection which is however concentrated within 02 MFIs (29%) which contributed

for 54% of the total deposit of the entire network in 2011. If for the first

MFI (CREC of Méckhé), the situation is due to the involvement of

its groups membership, the second (MEC of Tattaguine) owes its records to its

savings policy mainly based on high rate of compulsory savings (33%) as

requirement for loan application.

Regarding the credit delivery, it appears that except ordinary

loans, most of the loan products catered for are seasonal or working capital

loans and investment loans (more than one year) with bullet repayment albeit

variability in the loans maturity.

To provide such credit products, MFIs rely on three main

sources: the deposits, the borrowings and their equity. Most of the MFIs

provide their loans from the member's deposits and tend to report improvement

of their leverage except the MEC of Dakar and that of Malicounda.

Overall, all the MFIs loan portfolios are growing with an

average growth rate of 17% except the CREC of Méckhé which faced

a decrease in its portfolio of about 47% over the four years. However this MFI

still records the highest gross portfolio amount compared to the others.

Nevertheless, the growth in portfolio is facing also a growth

in portfolio at risk 180 days for all the seven surveyed MFIs meaning some

weaknesses in the loan portfolio management.

In contrast to the PAR, some improvements are reported in

operating expenses ratios which were roughly fewer than 20% except at the MEC

of Dakar which mostly recorded OER over 40% in 2011 and at the MEC of

Malicounda with about 90% in 2009.

As consequence, the OSS of the entire 07 MFIs was appreciable

between 2008 and 2010 (127%-148%) but dropped down to 88% in 2011 due to high

operating expenses at the MECs of Tattaguine and Pékesse.

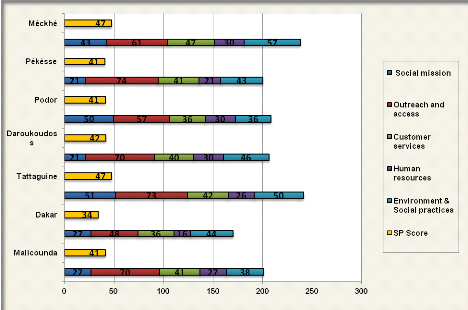

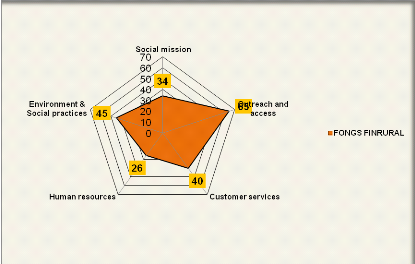

The results also reveals that albeit claiming to be social

oriented MFIs, the entire MFIs lack adequate tools, information and indicators

to track and to prove that they are putting into practice their social mission,

which often was not clearly stated. Based on the ECHOS(c) scale, it appears

that the MFIs recorded low social performance in general (55%) but seemed to

get better score in access and outreach and customers services, while social

mission, human resources and social responsibility are lessened.

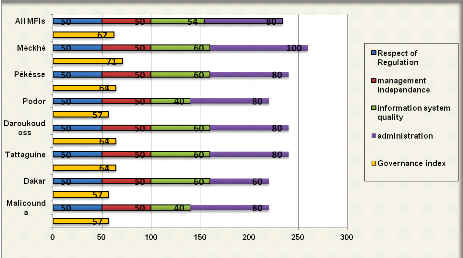

Regarding the governance, the score reveals some acceptable

governance (62%) however with some differences between institutions.

The results of linkages between financial performance, social

performance and governance reveals no trade-off between financial and social

performance, rather it reveals significant synergies between governance and

social perform, and between OSS and human resources.

All these results prove that rural microfinance institutions,

rather rural microfinance network can be viable. It is just a matter of more

governance, more discipline in procedure and more reportage of required

information.

RESUME EXECUTIF

Le but du présent mémoire est d'évaluer

la viabilité du réseau FONGS FINRURAL, un réseau en

construction de neuf mutuelles d'épargne et de crédit

exerçant en milieu rural sénégalais. Il vise d'une part

à apprécier la variabilité entre les différentes

mutuelles du réseau en ce qui concerne la performance financière,

la performance sociale et la gouvernance ; et d'autre part à

apprécier la contribution de chaque mutuelle à l'atteinte des

objectifs de viabilité du réseau.

L'approche méthodologique a essentiellement

consisté en d'une part l'exploitation des états financiers, des

plans d'affaires, des rapports et procès verbaux ainsi que de tous

documents jugés utiles pour notre étude ; et d'autre part en

des visites de terrains au niveau des mutuelles à la base

couplées d'entretien avec le personnel et les membres usagers.

L'unité d'observation est constituée de 7 sur

les 9 mutuelles affiliées au réseau faute de disponibilité

des données et de fonctionnalité de deux mutuelles.

Les données ont été collectées

à l'aide de quatre outils principaux : le factsheet

d'évaluation de la performance financière des institutions de

microfinance élaboré conjointement par BRS et ADA, l'outil

ECHOS(c) d'Incofin pour l'évaluation des performances sociales (version

2012), la grille de l'indice agrégé de gouvernance et les guides

d'entretien élaborés spécifiquement au niveau de chaque

mutuelle en fonction des différents résultats obtenus sur le plan

des performances financière et sociale ainsi que sur le plan de la

gouvernance.

Les données financières ont été

collectées sur les quatre dernières années (2008-2011)

alors que les données inhérentes à l'évaluation de

la performance sociale et de la gouvernance présentent l'état

actuel des mutuelles dans ces domaines.

Différentes statistiques descriptives nous ont permis

de faire des comparaisons. Le coefficient de corrélation de Spearman

nous a permis d'apprécier les synergies et les compromissions qui

peuvent exister entre les trois aspects de la viabilité.

Il ressort de l'analyse entre les IMFs que le

sociétariat essentiellement dominé par les femmes (50%) est en

pleine croissance avec un croît moyen de 23% nettement supérieur

au croît moyen de l'ensemble du pays (8.7%) dans le domaine avec

toutefois quelques spécificités selon chaque mutuelle.

Dans le même ordre d'idée, il a été

enregistré une augmentation de l'épargne mobilisée qui est

toutefois concentrée au niveau de deux mutuelles (29%). Ces deux

mutuelles détiennent à elles seules 54% de la totalité de

l'épargne mobilisée par l'ensemble des mutuelles. Si pour la

première mutuelle (la CREC de Méckhé) la situation est due

à la forte implication des groupements sociétaires, tel n'est pas

le cas au niveau de la seconde mutuelle (MEC de Tattaguine) qui doit sa

position à sa politique de mobilisation de l'épargne axée

sur l'épargne nantie et l'épargne obligatoire de près de

33% comme condition indispensable pour l'accès au crédit.

En ce qui concerne donc l'octroi du crédit, les

principaux crédits octroyés sont des crédits de campagne

et des crédits d'investissement à une seule

échéance de remboursement, en dépit de la

variabilité dans la durée des prêts. Ces crédits

sont octroyés à partir de trois sources de financement : les

dépôts ou épargnes des membres, les prêts et le

capital social. La plupart des crédits sont octroyés à

partir des dépôts entraînant ainsi une baisse de l'effet

levier du fait de l'augmentation du capital.

Dans tous les cas, on assiste à une forte croissance du

portefeuille de crédit au niveau de l'ensemble des mutuelles avec un

croît moyen de 17% l'an à l'exception de la CREC de

Méckhé qui, tout en détenant le portefeuille de

crédit le plus élevé, a subi une baisse de croissance de

l'ordre de 47% sur les quatre années écoulées.

Cette croissance du portefeuille de crédit est

malheureusement associée à une croissance du crédit en

souffrance après 180j. Ceci est observable au niveau de l'ensemble des

mutuelles (avec toute fois quelque légères différences),

conséquence des difficultés de gestion du crédit.

A l'opposé du portefeuille en souffrance, des

améliorations notables sont enregistrées au niveau du ratio des

dépenses opérationnelles avec un taux globalement

inférieur à 20% à l'exception d'une part de la mutuelle de

Dakar qui a enregistré un ratio de 40% en 2011 et de la mutuelle de

Malicounda avec un ratio de 90% en 2009.

Ainsi l'ensemble du réseau affiche une autosuffisance

opérationnelle acceptable entre 2008 et 2010 (127%-148%) mais qui a

néanmoins été affectée de façon

négative (88%) par les dépenses opérationnelles des

mutuelles de Pékesse et de Tattaguine en 2011.

Les résultats révèlent par ailleurs que

malgré la revendication des mutuelles d'avoir des approches sociales,

elles manquent d'outils adéquat, d'information et d'indicateurs

pertinents pouvant permettre d'apprécier l'efficience de la mise en

application de leur mission sociale qui d'ailleurs n'est pas souvent clairement

définie. Les résultats obtenus à partir de l'outil

ECHOS(c) affichent d'ailleurs que l'ensemble des mutuelles a une faible

performance sociale (55%) même si certaines percées sont

enregistrées au niveau de deux dimensions : l'accès et le

taux de pénétration ainsi que les services aux membres.

Sur le plan de la gouvernance, il ressort que les mutuelles

présentent globalement une gouvernance appréciable (62%) avec

néanmoins de grandes variations entre elles.

Le test de corrélation de Spearman entre les trois

dimensions montre l'absence de compromis entre la performance social, la

gouvernance et la performance financière. Il révèle par

contre des synergies significatives entre la gouvernance et la performance

sociale d'une part et entre l'autosuffisance opérationnelle et les

ressources humaines d'autre part.

L'ensemble des résultats prouvent enfin que les

institutions rurales de microfinance, mieux les réseaux ruraux de

microfinance peuvent être viables. Il s'agit d'une question de

gouvernance, de plus de discipline dans les procédures et de plus de

capitalisation de l'ensemble des expériences en microfinance et ceci en

relation avec les informations requises dans le secteur.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Dedication

i

Foreword

ii

Acknowledgments

iii

EXECUTIVE SUMARY

iv

RESUME EXECUTIF

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

x

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS, SIGLES AND

ACRONYMES

xii

LISTE OF FIGURES AND TABLES

xiii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1

1.1 Problem statement

1

1.2 Objectives

3

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF LITERATURE, RESEARCH

QUESTIONS AND METHODOLOGY

4

2.1 Review of literature

4

2.1.1 Main dimensions of viability: financial and

social performance

4

2.1.2 Other dimensions of viability analysis

6

2.2 Research questions

8

2.3 Methodology

8

2.3.1 Data collection

8

2.3.2 Data analysis

9

CHAPTER THREE: BACKGROUND OF THE

MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY IN SENEGAL

11

3.1 A growth led by savings and credit unions

11

3.2 Rural areas are still under banked and

underserved

12

3.3 A strong legal and juridical framework

13

3.4 Leading networking initiatives

15

3.5 Why networking?

16

CHAPTER FOUR: FONGS AND FONGS -FINRURAL

19

4.1 From failures to new financial initiatives

19

4.2 The FAIR, the start up of the networking

process

20

4.3 Overview of FONGS FINRURAL

21

4.3.1 Operating areas

21

4.3.2 Membership

22

4.3.3 Delivering flexible financial services

23

4.3.4 Sources of funding

29

CHAPTER FIVE: PERFORMANCES ANALYSES

31

5.1 Financial Analysis

31

5.1.1 Portfolio Management

31

5.1.2 Efficiency

34

5.1.3 Profitability: Cost Ratio Analysis

36

5.1.4 Sustainability

38

5.2 Social performance Analysis

41

5.3 Governance Analysis

44

5.4 Linking financial performance, social

performance and governance in MFIs

45

5.6Toward sustainability: An endless fight

47

CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSION

49

References

51

ANNEXES

54

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS,

SIGLES AND ACRONYMES

|

ACAPES

|

:

|

Association Culturelle d'Auto Promotion Educative et Sociale

|

|

ADA

|

:

|

Appui au Développement Autonome

|

|

AFD

|

:

|

Agence Française de Développement

|

|

ARAF

|

:

|

Association Régionale des Agriculteurs de Fatick

|

|

ASESCAW

|

:

|

Amicale Socio-économique Sportive et Culturelle des

Agriculteurs du Walo

|

|

BRS

|

:

|

Belgian Raiffeisen Foundation

|

|

COPED

|

:

|

Coopérative des Groupements de Producteurs et Eleveurs du

Delta

|

|

COPI

|

:

|

Comité de Pilotage

|

|

CPEC

|

:

|

Caisse Populaire d'Epargne et de Crédit

|

|

CREC

|

:

|

Coopérative Rurale d'Epargne et de Crédit

|

|

FONGS

|

:

|

Fédération des Organisations Non Gouvernementales

du Sénégal

|

|

FONGS FINRURAL

|

:

|

Réseau FONGS Finance Rurale

|

|

GTZ

|

:

|

Deutsche Gesellshaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit

|

|

MFI

|

:

|

Microfinance Institution

|

|

Inter CREC

|

|

Réseau de Coopératives Rurales d'Epargne et de

Crédit

|

|

MEC

|

:

|

Mutuelle d'Epargne et de Crédit

|

|

MFR

|

:

|

Maisons Familiales Rurales

|

|

MECSAPP

|

:

|

Mutuelle d'Epargne et de Crédit de la Solidarité

pour l'Auto - Promotion Paysanne dans l'Arrondissement de Tattaguine

|

|

SAPPATE

|

:

|

Solidarité pour l'Auto - Promotion Paysanne dans

l'Arrondissement de Tattaguine

|

|

SOS FAIM

|

:

|

Development Belgium and Luxembourg Non Governmental Organization

fighting against hunger and poverty in rural areas in Africa and in Latin

America

|

|

UGPM

|

:

|

Union des Groupements de Producteurs de Méckhé

|

|

UGPN

|

:

|

Union des Groupements des Producteurs des Niayes

|

|

UMOA

|

:

|

Union Monétaire Ouest Africaine

|

LISTE OF FIGURES AND

TABLES

Figure 1: Evolution of MFIs' juridical forms

2005-2010

1

Figure 2: Number of MFIs services points as of

December 2010

13

Figure 3: Linkages, technical and financial

flows between FONGS and FONGS FINRURAL

20

Figure 4: Membership as of December 2011

22

Figure 5: MFIs contribution to the network

saving mobilization in 2011

24

Figure 6: Split of loan products in 4 MFIs in

2011 as % of the GLP

26

Figure 7: Leverage (Debt/Equity)

29

Figure 8: Portfolio At Risk over 180 days

2008-2011

32

Figure 9: Operating Expenses Ratios

2009-2011

34

Figure 10: Portfolio yields 2009-2011

35

Figure 11: Cost Ratios 2008-2011

37

Figure 12: Returns on Assets 2009-2011

38

Figure 13: Operational Self Sufficiency

2008-2011

40

Figure 14: Breakdown of portfolio yield

2011

41

Figure 15: Social Performances of the Seven

MFIs

42

Figure 16: Social performance of FONGS

FINRURAL

43

Figure 17: Aggregated Index of Governance

44

Table 1: Correlations between OSS, Social Performance Indicators

and Aggregated Index of

Governance...................................................................................................................................

.....46

CHAPTER ONE:

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Problem statement

For the last two decades, the (West) African Region has been

experiencing a drastic growth in the microfinance industry (Périlleux,

2010). This growth is mainly characterized not only by the creation of

numerous and various microfinance institutions (MFIs) from savings and credit

groups to non-bank microfinance institutions, but also by a tremendous growth

in term of beneficiaries (Lafourcade, Isern, Mwangi & Brown, 2005; Labie

& Périlleux, 2008).

Whereas some of these MFIs are registered and even licensed,

many others still operate informally, leading to serious deficiencies and

crises in the industry. One of the most recent cases is that of

ICC-Services1(*) and kinds

in Bénin where more than 161 billion CFA were unfortunately robbed from

public depositors (BAfD, OCDE, PNUD and CEA, 2011). In order to avoid such

problems, the UMOA (Union Monétaire Ouest Africaine)2(*), a West African monetary

institution, had previously refined the legal environment of the

Systèmes Financiers Décentralisés

(SFD)3(*) by reviewing

the PARMEC4(*) law in April

2007.

The Republic of Senegal was the second country of UEMOA that

adopted the new law in 2008 with the appellation of law 2008-47.

One innovation in the new law is the withdrawal of Savings and

Credit Groups and the necessity for basic mutuals and cooperatives to federate

into unions or networks. The basic idea was to improve the microfinance

industry management and make a better follow up of the MFIs. Secondly, it aimed

at improving the implementation of good practices among MFIs, thus helping them

to perform both socially and financially.

FONGS, a farmers' organization in Senegal decided to set up a

savings and credit unions network for its members in order to facilitate their

access to financial services. Those savings and credit mutuals, have started

with the process to get in line with the new regulation. However, the network

is not regulated yet. With regard to all the problems savings and credit unions

or mutuals are facing particularly in Western Africa, it seems very important,

before going further in the licensing process, to assess whether those mutuals

are currently viable.

The viability issue appears important in the microfinance

industry since MFIs need financial resources to continuously and sustainably

provide financial services to their clients or members. To come up with this

situation, MFIs use various strategies to sustain their financial resources

through the minimization of operating expenses, a better financial management

and good administration (Ben Soltane, 2012). As these strategies are not

sufficient, MFIs need to intermediate additional resources from commercial

banks, they also need assistance from donors. However, with the global

financial crisis, international funds are becoming scarce and difficult to

capture. Thereafter the rational becomes that financial support should be

granted to MFIs holding the expected capacity of absorption and implementing

governance and management mechanisms (Hudon, 2007). Therefore, MFIs have the

challenge to build confidence and trust to attain their own financial

sustainability, and design adapted financial mechanics to attract funds,

helping them to realize economies of scale (Ben Soltane, 2012). These

confidence and trust might be built if MFIs are viable, socially and

economically.

The present thesis which is the result of the research

effectuated in the framework of our complementary master in microfinance

endeavours to give some insights about that viability issue especially within a

rural microfinance network.

In this first chapter we raised up the viability issue of MFIs

involved in a networking process regarding the new legal requirements within

UMOA region and objectives of the study as well.

In the second chapter we presented through a literature review

an overview of the current mainstreams regarding financial and social

performance of MFIs, the synergies and trade-offs highlighted by scholars and

practicians. Likewise, we presented both the research questions and the

methodology approach used.

The third chapter depicted the microfinance industry in

Senegal, the new regulation and networking dynamics.

The chapter four pinpointed the FONGS FINRURAL network as the

main object of the study pertaining to operations' areas, membership along with

financial products delivery and funding structure.

In the chapter five we deepened our study on the performance

analysis. First we strived to assess the financial performance through four

main dimensions. Secondly we discussed about the social performance and the

governance issue. We tried also to build a link between financial performance,

social performance and governance. Then we made a global analysis about all the

results obtained.

In the chapter six we made a global synthesis of the research,

the main lessons learned and the challenges for future.

1.2 Objectives

The ultimate objective of this research is to assess the

viability of FONGS FINRURAL network. More specifically, this research aims at:

- Assessing the financial and social performance of FONGS

FINRURAL network and its affiliated associations;

- Assessing the governance of the associations affiliated to

the network as well as of the network.

At the end of this study, FONGS FINRURAL and its partners are

aware of the performance of the network as well as its strengths and

weaknesses. Thus, relevant decisions for a better sustainability can be taken

and implemented.

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF LITERATURE, RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND

METHODOLOGY

2.1 Review of literature

Throughout this section, we provide conceptual explanation of

key terms used for a better apprehension of the thesis. The section is divided

in two parts: the foremost focuses on the main dimensions of viability, the

second focuses on social viability and governance.

2.1.1 Main dimensions of viability: financial and social

performance

2.1.1.1 Financial performance

Financial performance is commonly defined as the measure of

efficient utilization of assets by a company to create revenue. It can be also

viewed as a general appraisal of a company's financial statement over time, and

accordingly can help analyze identical companies inside the same industry or

compare aggregated industries or sectors5(*). Though there are many financial indicators in finance

sector many practitioners and scholars (Mersland, Randoy & Strom, 2010;

Kumar, 2011) usually focus on Return on Assets and Return on Equity.

Mersland, Randøy & Strøm (2010) used

indicators such as Return on Assets (ROA), Operational Self-Sufficiency (OSS)

and Financial Self-Sufficiency (FSS) to assess the financial performance of

microbanks. They found that most of the microbanks in their survey were not

financially self sufficient even though they could meet their obligations.

Nevertheless, while in bank sector the financial performance

is usually measured through the ratios above mentioned, the trend in

microfinance is to include on top of them others indicators enabling a better

understanding of the specificities in this industry. These indicators include

the interest rate, the arrears or the repayment rate, the level of activities,

the aptitude to collect savings, the financial and operational costs, the level

of client oriented priority, the expansion costs etc (ACDI, 1999 quoted by

Diao, 2006).

Moreover, BRS6(*) and ADA7(*) used the financial performance indicators proposed by

von Stauffenberg, Janson, Kenyon & Barluenga-Badiola (2003) and Barres et

al. (2006) to elaborate a factsheet helping at assessing MFIs'

financial performance. The latter seems relevant for out study.

2.1.1.2 Social performance

Social performance is widely perceived as the effects of an

organization on the social life of its clients. It refers to the internal

relations between an institution, its employees and others stakeholders with

whom it interacts (Lapenu, Zeller, Grelley, Chao-Béroff & Verhagen,

2004). On the other hand, social performance refers to the effective

application of the social mission of an organization (Dewez & Neisa, 2009;

IFAD8(*), 2006). In

microfinance, social objectives usually include the bread and the depth of

outreach, the adequacy of the services to the needs of clients as well as the

quality of those services, the outcome for the clients and their social

networks, the commitment of the MFI vis-à-vis its staff, its clients and

its environment (IFAD, 2006).

Mersland, Randøy & Strøm (2010) used the

outreach with three criteria as a proxy to social performance or mission: the

outreach to the poorest, the outreach to women, and the outreach to rural

areas.

However, for IFAD (2006), social performance is not only

limited to the measurement of objectives and outcome. Social performance is

also concerned with actions and measures used by an MFI to obtain those

results. Basically, social performance is about how well MFIs give themselves

the means for their social mission. The aim is to determine whether the MFI

gives itself the means to reach its social goals by tracking improvement

towards the latter and understanding how to use the information to make

improvements in its operations.

Many tools exist in the industry for a better understanding

of social impact among which the Social action developed by Accion

International, the ECHOS(c) designed by Incofin, The Social scoring tools

presented by specialised microfinance institution, and the Social Performance

Indicator developed by Cerise (Dewez & Neisa, 2009).

Nevertheless, regardless the tool, there is a widespread

understanding on the main dimensions a social performance analysis should

tackle while assessing a MFI. These dimensions are: target and outreach,

adequacy of products delivering and services, client participation and the

social responsibility of the MFI. We will focus on those dimensions in our

study.

2.1.1.3 Financial and social performance: synergies or

trade-off?

According to many authors and practitioners, MFIs always face

a situation of mission drift (Dewez & Neisa, 2009; Conning & Morduch,

2011; Ben Soltane, 2012) since reaching the double bottom line in microfinance

is quite a paradox. Nevertheless, the research findings about that specific

aspect are quite various. Whereas some authors have shown that there is a real

trade-off between achieving financial and social performance in microfinance

(Hermes, Lensink & Meesters, 2011), others such as Zerai & Rani (2012)

and Ben Soltane (2012) have found that there is neutral relationship between

financial and social performance; rather, they have deducted that it is

possible for a MFI to achieve both financial and social performance.

But for Gonzalez (2010), the situation of trade-off or synergy

depends essentially on the selected indicators or variables.

Our study will contribute to the improvement of this issue

which is currently riveting the industry.

2.1.2 Other dimensions of viability analysis

Another current mainstream in the microfinance industry is

that MFIs should be sustainable while providing their services. For long time,

institutionalisation was seen as the main factor of sustainability and was

focused only on financial and institutional viability (GTZ, 2002). However

there is a growing acknowledgment that financial performance only cannot help

MFIs to reach their missions (Pistelli, Simanowitz & Thiel, 2011). Thus,

social viability and governance appear as two other dimensions that should be

included for a better apprehension of the concept of sustainability (GTZ,

2002).

2.1.2.1 Social viability

For GTZ (2002), social viability can be seen as the completion

of a win-win trade-off on interest between different stakeholders having a

direct or indirect interest or link with the MFI. It is therefore a key concept

which, once well integrated may impact on the good functioning of MFIs.

GTZ (2002) identified two types of social viability:

- The internal social viability which focuses on the trade-off

relationship between actors directly linked to the MFI;

- The external social viability which includes the

mainstreaming of the MFI in local environment.

In general, practitioners and scholars focus mainly on the

internal social viability though the external one is quite important.

2.1.2.2 Governance

Progressively used in the microfinance industry, the notion of

governance is most often related to the functional relations between the

management board and loan officers who are daily involved in all the management

process of a given microfinance institution (GTZ, 2002; Lapenu & Pierret,

2006). Basically it refers to the processes whereby equity holders and others

financing agencies ascertain themselves that the use of their funds by the

institution is in line with the objectives they are dedicated to (Hartarska,

2005; Labie & Périlleux, 2008). More widely, governance may also be

concerned with many others issues in MFIs such as strategic objectives (clients

targeting, product design, organisational structure), resources allocation and

management, adaptation to the changes in the sector, crisis prevention and

management (GTZ, 2002; Lapenu & Pierret, 2006).

The good governance is a key element for MFIs sustainability

as the quality of governance affects the vision and strategy of MFIs regardless

their status (AFD, 2008). Moreover, for Mersland (2009), corporate governance

affects the way institutions perform. Particularly in cooperatives structures,

corporate governance tends to be more complex. Labie & Périlleux

(2008), through a relevant literature, emphasised the moral hazard, conflicts

between owner and manager, conflicts between members and elected board of

directors, conflicts between employees and volunteers as four main conflicts

encountered in credit unions' governance.

Therefore, the governance analysis appears as one key

component for assessing the viability of a MFI.

Mersland & Storm (2009) highlighted three dimensions to

look at whilst analysing the governance in a MFI: the «vertical

dimension» focused on the owners and the staff, the «horizontal

dimension» between the MFI and its clients and the «external

governance dimension».

On the other hand, based on IMF (2004) and Briceno-Garmendia

& Foster (2007), Wele (2009) proposed six variables with nine indicators to

assess the quality of governance in microfinance institutions. These variables

are: Respect of regulation, Managerial autonomy, Quality of the information

system, Power of board of Directors. He combined the analysis of theses

indicator with the analysis of the board structure and efficiency as proposed

by Mersland & Storm (2009).

2.2 Research questions

The present thesis will address three fundamental

questions:

- How do financial performance, social performance and

governance vary among FONGS FINRURAL affiliated associations?

- How do the different performances of the affiliated

associations of FONGS FINRURAL affect the viability of the network?

- To what extent are linked financial performance, social

performance and governance in the surveyed MFIs?

2.3 Methodology

Our methodology consisted essentially in:

- The use of internal documents such as minutes from board

meetings, business plan, manual of procedures, other secondary sources data;

- The use of data bases and annual reports when they exist,

financial reports, audited financial statements etc;

- Visits at basic associations and clients information.

- Observations

All these actions were carried out in the framework of the

internship effectuated within the FONGS from May to August 2012.

2.3.1 Data collection

Quantitative and qualitative data were collected at 07

affiliated MFIs and at the FONGS headquarters level as well.

Quantitative data were collected by using the financial

factsheets components, the ECHOS(c) tool for social performance data and the

grid for assessing the quality of governance.

Observation, Semi-structured and unstructured interviews were

used to collect qualitative data from main stakeholders of the MFIs.

Secondary data were collected through reports and existing

literature.

2.3.2 Data analysis

The analysis of data was an integrated analysis of three keys

elements of viability that are financial viability, socioeconomic viability and

institutional viability. These three elements are respectively assessed through

financial performance, social performance and governance analyses.

The financial performance has been assessed with the financial

assessment factsheet9(*).

Four categories of fourteen indicators were analysed: the portfolio quality,

the efficiency and productivity, the financial management and the

profitability.

The social performance has been assessed with the ECHOS(c)

Tool of Incofin. ECHOS(c) is Incofin Investment Management's in-house social

performance evaluation tool. The version used was the 2012 one, which takes

into account the most recent developments on social performance in the

microfinance industry. It focuses on five dimensions: social mission, Outreach

and Access, Customers services, Human resources, Environmental and social

practices.

The quality of governance of the basic organizations as well

as of the network has been assessed with the Aggregated Index of Governance.

The rational is that this index not only combines different aspects of

governance but also can be more easily because using particularly binary

variables (Wele, 2009). It focuses on six variables: the respect of the

regulation, the management autonomy, the information system quality, the board

of directors. Some variables from the analysis framework of Charreaux (1996)

have been transformed in binary variables and included in the Aggregate Index

of Governance: direct control by shareholders, existence of internal and legal

audit, existence of salaries bonuses and the financial intermediation.

For a better understanding of the drivers behind the disparity

between associations and the network, we used descriptive analysis mainly based

on frequency and mean. We used spearman coefficient of correlation to

appreciate the linkages between financial performance, social performance and

governance index in our analysis unit. This latter comprised 7 of the 9 MFIs

affiliated to the network due mainly to the data availability and to the

non-functioning of the two others the last two years. Besides, as the network

as a whole is not yet fully involved in the financial intermediation, the

effect of these missed MFIs on the network can be minimized.

CHAPTER THREE: BACKGROUND OF THE MICROFINANCE INDUSTRY IN

SENEGAL

3.1 A growth led by savings and credit unions

The microfinance industry in Senegal is a growing sector

marked by the prominence of numerous MFIS, NBFIs and Savings and Credits

Cooperatives or Mutuals. Three wide periods determine the microfinance growth

in Senegal (Fall, 2012):

§ The First period was characterized by the financial

crisis of eighties along with the creation of the first credit and savings

institutions. During that period, a temporary framework related to the

conditions of organizing, licensing and functioning of Savings and Credit

Mutuals (decree n° 1702 of 23-02-1993) was set up and admitted 120 MFIs to

be licensed. However no disposition of that law addressed the regulation issue

of the «Groupements d'Epagrne et de Crédit (GEC)»10(*).

§ The second period (1993-2003) was marked by the

enforcement of the legal framework on Decentralized Financial Systems (so

called PARMEC law). That period was mainly influenced by the growth of the

industry and the creation of MFIs' networks such as Unions, Federations, and

Confederations which appeared as apex or umbrella institutions.

§ The Third period (2003-nowadays) is mainly dominated by

the commercialization and the professionalization of the industry. During that

period, MFIs are more focused on risks management issues and the reinforcement

of the supervision of the industry. Especially, one observes a professional

management of institutions, an effective control of network staff, and a focus

on a good financial and institutional equilibrium.11(*)

As of December 2010, the microfinance industry in Senegal was

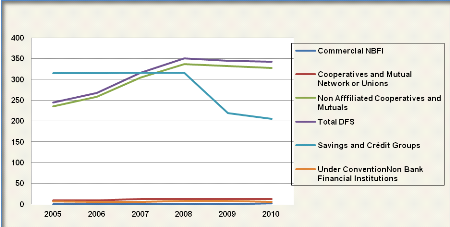

composed as depicted in the figure 1.

Figure 1: Evolution of

MFIs' juridical forms 2005-2010

Source: Built from MEF/DRSSFD

(2010, p.2)

It appears through the figure 1 that savings and credit groups

which dominated the industry between 2005 and 2007 recorded a decrease since

2007 due to the new regulation. Concurrently one witnesses the growth of

isolated savings and credit cooperatives and mutuals as well as MFIs' networks.

On the other hand, commercial non bank microfinance institutions are entering

the sector whereas under convention non bank financial institutions are

dropping out. Nonetheless, the industry is still dominated by the savings and

credits unions which provide the essential in microfinance services. For

example the seven most renowned savings and credit unions networks of Senegal

network concentrate about 70% of the clients/members, 88% of deposits and 82%

of outstanding loan portfolio of the industry since 2005 onwards (Daouda, 2006

quoted by SOS FAIM, 2007).

3.2 Rural areas are still under banked and underserved

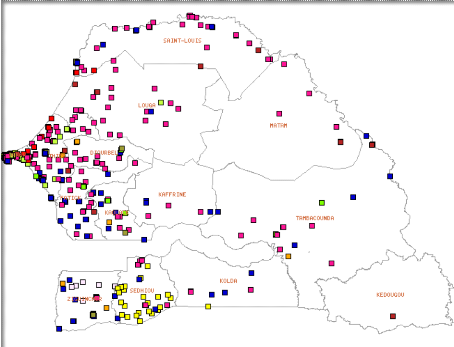

As of December 2010 the number of services points of MFIs was

976 with an individual outreach of 12% (MEF/DRSSFD, 2010) representing more

than 21% of services points, 24% of loan portfolio and 22% of deposits of the

total finance sector (Diao, 2006).

Despite the increase in number of MFIs in the number of

clients, the microfinance in Senegal is still more urban and sub-urban than

rural. The figure 2 shows the geographical outreach of microfinance industry in

2010.

Figure 2: Number of MFIs

services points as of December 2010

Source: MEF/DRSSFD (2010,

p.3)

The figure 2 reveals that more than 70 % of the MFIs operating

in Senegal and their branches are located exclusively in urban areas including

Dakar, Thiès and someway Kaolack, Fatick, Sedhiou and Saint Louis. As

consequence, poor people living in rural and remote areas remain still

unbanked. The other 30% MFIs, most often created from farmers and rural

development organizations, are struggling to reduce the gap, allowing poor

people having access to finance even with tiny amount of credit.

3.3 A strong legal and juridical framework

The microfinance legal environment has evolved over the time

in West Africa Region Countries especially in those belonging to the West

African Monetary Union.

The first initiative of implementing a strong institutional

framework for the microfinance in Senegal has been observed with the

«Projet d'Assistance Technique aux Operations Bancaires Mutualistes au

Sénégal» (ATOMBS). The project was carried by the Canadian

Cooperation and aimed at creating adequate conditions for the development of

the mutualist banking network. In 1992, the «Cellule AT/CPEC12(*)» in charge of organizing

the conditions of functioning and licensing of mutualist institutions continued

the project.

The juridical and institutional framework was effective in

1995 after the adoption of the PARMEC Law and its enforcement decree (decree

n°097-1106 of 11 November 1997) sustained by the BCEAO instruction on 10

march 1998. The PARMEC law aimed at designing and promoting the extension of a

juridical environment specifically devoted to the microfinance in UMOA context.

Another project PASMEC (Projet d'Appui aux Strutures

Mutualistes et Coopératives d'Epargne et de Crédit) was set up to

promote the development of microfinance practice in UMOA as well as the

financing of small and medium enterprises (SME) and handcraft. The operation

permitted the devising of guidelines for the microfinance industry strongly

based on the success stories of microfinance practices around the world (Diao,

2006).

However, important weaknesses were observed in the legal

framework of UMOA MFIs.

§ The PARMEC law emphasised the development of MFIs with

cooperative models, restricting thus the development of other models of MFIs

such as limited companies in their various forms. That situation hampered

innovations in the industry and accordingly the diversity of financial services

for the poor (Fall, 2012);

§ The short term authorization given to non Bank

Financial Institutions other than Cooperatives and Mutuals undermined

investment in the industry as well as access to financial markets and long term

commercial borrowings;

§ The OHADA agreement on the guarantee and tangible

collaterals and the recovery policies didn't fit with microfinance industry

realities;

§ The transformation of NGO MFIs to regulated MFIs was

undermined by the law of 1901 on associations.

§ The contents of the law on usury didn't include MFIs'

realities thus hindering their viability.

§ The prudential ratios were not standardized for NBFI

and comparisons in the industry appeared difficult (Azocli & Adjibi,

2007).

The new regulation on Decentralized Financial Systems was

adopted by Senegal Government on 03 September 2008 through the Law 2008-47. The

main changes or initiatives in the new regulation are as follows:

§ The origination of a single policy for the regulation

of MFIs involving the removal of the savings and credit group and of the

structures under convention as well

§ The assent of the BCEAO in the issuance of the

license

§ The intervention of the BCEAO and the Banking

Commission in the supervision of institutions having reached a certain level of

growth

§ The strengthening of the prudential norms and the

penalties,

§ The mandatory certification of accounts of MFIs of a

certain size

§ The compulsory membership within the Professional

Association of MFIs Practitioners

§ The alternative of creating Limited MFI Companies

§ The implementation of a new accounting standards for

MFIs (Fall, 2012, p.38)13(*)

Its application decree (n° 2008-1366 of 28 November 2008)

and other BCEAO instructions designed strong framework to supervise the

industry and avoid drifts. In addition, the regulation's new requirements and

devised prudential ratios compel MFIs to become viable (financially mainly), to

network or to disappear.

3.4 Leading networking initiatives

As of December 2011, about twenty microfinance institutions

networks exist in Senegal. Among these, only thirteen are regulated.

Nevertheless, depending on their implementation process and regardless they

licensing status, they can be classified in two main categories (SOS-FAIM,

2007):

- The first category is related to networks that have been

devised and implemented based on a top-down approach. The creation of new

branches is done in the network expansion perspective and those networks are

supported or have been supported by international donors, NGOs, public

organisms of international cooperation. Belonging to that category, we can name

the Credit Mutuel du Sénégal (CMS), the Alliance de Credit et

d'Epargne pour la Production (ACEP), and the UM-PAMECAS14(*). These three networks started

their activities as development projects supported and financed by

international donors and appear nowadays as the most important stakeholders of

the microfinance industry in Senegal. Most of these networks were set up in

1997.

- The second category is related to networks that have been

set up based on existing MFIs and Village Banks. MFIs created from local

development associations initiatives decided to cooperate and to federate in

unions in order to improve their efficiency and viability. As the MFIs were

different at the beginning, they need to standardise their procedures and

products. Two main subcategories belong to that group depending of the origin

of the networking.

Ø The networking initiative may be exclusively

endogenous as well as the process of implementation. It is the case of the

Inter-Crec Network with 17 savings and credit unions operating in

Basse-Casamance in Southern Senegal.

Ø The networking initiative may be partially exogenous

and supported by international partners. This is the case of the initiative of

creating a network in Louga Region with the support of two international NGOs:

Aquadev (from Belgium) and CISV (from Italy). The initiative is funded by the

European Commission. This is also the case of FONGS FINRURAL Network, which is

a joint initiative of the Fédération des Organisations Non

Gouvernementales du Sénégal (FONGS) and its partner SOS-FAIM

(Belgium and Luxembourg)

3.5 Why networking?

Even if the new law promotes the networking of individual

MFIs, the process is not an easy task as networking implies many challenges and

transformations within the MFIs. SOS-FAIM (2007) emphasised five main

advantages in networking savings and credit unions:

§ The first advantage underlined is a better liquidity

management. Due to the principle of mutualisation, the surplus of cash in some

MFIs might be used by others MFIs in need of more cash to face their portfolio

growth. The network then operates like a central bank in gathering the cash

surplus and in redistributing it to MFIs equitably (fairly, evenhandedly). As

MFIs do not usually have the same cash flow cycle, the network management can

help at smoothing the cash flows fluctuation between affiliated institutions.

In addition, the network could better manage the liquidity through financial

investments as it can access to financial markets.

§ The second advantage is the access to external funds

such as commercial markets, international donors and Microfinance Investment

Vehicles Funds. The individual MFIs do not always have a good accounting system

and accordingly lack of support from banks, donors and NGOs. Yet, the access to

external lines of credit can be useful in long term for MFIs for a better

management of their short and long term liabilities.

§ The networking helps in scaling economies by reducing

the cost of a MIS15(*) for

exemple, the staff training cost, the hiring of experts etc...

§ By networking, MFIs offer themselves opportunities and

framework for sharing experiences, goods practices, and information. Moreover,

the network operates as a Central for Risk Management, thus avoiding multiple

borrowings to clients and over- indebtedness through a good credit bureau

between affiliated MFIs.

§ The network can also reinforce internal and external

controls, from staff of the network headquarters, the hiring of auding experts,

on top of the Supervisin of the Central Bank.

However, the same author raised up some drawbacks:

§ The partial loss of independence and autonomy of

affiliated organizations. Due to the standards and the requirement of the

network, an affiliated MFI might be obliged to transfet part of its comptences

to the network (liquidity management for example).

§ The presence of the network can threaten the membership

inside MFIs and induce a loss of members control on MFIs especially when more

professional staff members should be hired by the network.

§ It becomes mandatory for the network to standardizes

the management procedures, the credit policies, the management tools, and data

collections.

§ The mutualisation of cash surplus seems to be a key

condition for the networking. Affiliated MFIs are therefore jointly financially

liable and have to share the same vision in oder to improve synergies between

basic units and the social cohesion inside the network (SOS-FAIM, 2007).

CHAPTER FOUR: FONGS AND FONGS -FINRURAL

4.1 From failures to new financial initiatives

The «Fédération des Organisations Non

Gouvernementale du Sénégal» (FONGS) is a rural households

apex association originated in 1976 and licensed in 1978. It aims at restoring

the farmers' status through the accountability and the empowerment in

solidarity in order to address different challenges of rural areas. It is

composed of more than 150000 members split in 31 affiliated associations

throughout different regions of the country (Périlleux, 2011; Ndiaye,

2012)

The FONGS initiative is performed through two main axes:

- The political axis which is involved in the farmers' welfare

advocacy by fostering social and technical intercourse amongst affiliated

organizations and by lobbying.

- The economic axis is related to the capacities building of

rural households, the strengthening of agricultural management, the betterment

of local financial systems, and the enhancement of agricultural products added

values (FONGS, internal document).

To attain the economic axis, a number of initiatives have been

performed from 1984 to 1992 through financial operations, credit backing to

affiliated associations, agricultural commodities exchanges programmes, etc.

Unfortunately, many of those initiatives were abortive due to four main

reasons:

- Targeting failures: Credits were catered for people who

could not repay and unremarkably defaulted.

- Lack of efficient means and procedures for the scrutiny of

funded activities;

- Mismatches between projects submitted by associations'

leaders and the reel needs of members;

- Mission drift in the allotment of the financial resources

incurred from donors and partners (FONGS FINRURAL, 2011)

It has appeared that the FONGS' mission was not to directly

cater financial services for its affiliated development associations; which

have therefore been supported to launch self-managed and free savings and

credit unions to face up financial needs of their members. Thenceforth, the

mutuals were set up as twin associations of mother associations of which they

were perceived as the main financing tool.

4.2 The FAIR, the start up of the networking process

One major project carried out by the FONGS remains the

Facilité d'Appui aux Inititaives Rurales funded by Luxembourg government

through the NGO SOS FAIM (Belgium and Luxembourg). This initiative was

conceived as a response to miscellaneous unmet financial investment needs of

rural households.

With a global cost of about 514 millions CFA, one part of the

fund assists household investment needs through long term investment loans (325

millions CFA). The second part of the fund (190 millions) helps at subsidising

technical assistance to 15 MFIs through which investment loans are provided to

rural households in accordance with FONGS affiliated associations.

Started since 2007 the project endeavoured at experiencing the

rural investment through new financing models: no collateral, low interest

rates, flexible long term repayment schedules, etc... After five rounds of the

project through which about 353 millions CFA were disbursed to found 257

projects it appeared important to strengthen MFIs involved in the project by

networking them (Ndiaye, 2012).

The figure 3 below illustrates the links between surveyed MFIs

and farmers' organizations affiliated to FONGS:

Figure 3: Linkages,

technical and financial flows between FONGS and FONGS FINRURAL

Orientation, Financial and Technical

support

FONGS-FINRURAL

FONGS-Action Paysanne

Rural Households (RHH) and other basis

organizations

Savings and Credit Unions

Rural and Sub Urban Associations

Rural Households (RHH) and other basis

organizations

Financial and Technical support needs:

Source: Our survey (mai-august

2012)

Existing Financial Products Needs:

Technical support delivery:

Financial Product designing and delivery :

A foremost analysis on this framework shows up that financial

needs of rural households should first be reported to their development

associations which will transfer the information to the upper levels of FONGS.

Thenceforth, the finance network will base both on its financial assets and on

the FONGS vision to devise and provide required loan products to rural

households accordingly.

The main concern of this process is to preclude a

mismanagement of FONGS and its partners' funds directed to financial needs of

rural households, thereafter help improving rural households' financial access.

Besides, strong links could be sustained between the finance network and FONGS

and permit credit policies and strategic orientations of mutuals to unceasingly

meet with FONGS vision and needs of farmers organizations, unheeding the

growing competition in the industry.

4.3 Overview of FONGS FINRURAL

4.3.1 Operating areas

The FONGS FINRURAL network comprises 09 MFIs performing in 3

of the 7 agro-ecologic regions of Senegal: the «peanut basin», the

«valleys», and the «Niayes» renowned as important rural and

agricultural areas aside from the southern of the country, and constituting

about 30% of the surface of Senegal. These MFIs are the following: MEC MFR of

Malicounda, MEC SAPP of Tattaguine, MEC ARAF of Gossas, MEC MFR of

Pékésse, CREC UGPM of Méckhé, MEC UGPN of Darou

Koudoss, MEC FAM of Dakar, MEC COPED of Ross Béthio and MEC Koyli

Winrdé of Podor.

The remaining part of this paper will focus only on seven MFIs

owing to the inactivity of the MEC ARAF of Gossass and COPED of Ross

Béthio the past two years (2010 and 2011) for governance concerns.

Likewise, the data's nonentity of the two MFIs hindered their inclusion in

analyses.

All the other seven MFIs involved in the networking process

recorded diversity of experiences pertaining to their operating areas. The

average experience in the industry is about eight years, the MFI of Dakar

appearing as the eldest MFI while the MFI of Malicounda is at its early stage

of development. The experiences recorded by the MFIs (minimum of 4 years) are

important to have some insight about their performances and how they can affect

the viability of the network.

4.3.2 Membership

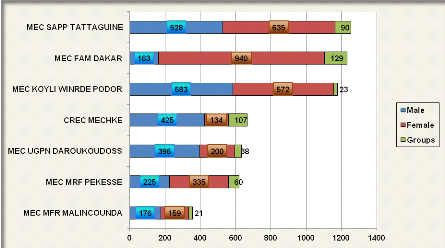

The figure 4 illustrates the membership situation of the MFIs as

of December 2011.

Figure 4: Membership as of

December 2011

Source: Our survey (may-august

2012)

It appears through the figure 4 that the Network affiliated

MFIs can be assorted in three wide groups while considering the accession

number: those who hold more than 1000 members (43%), those with membership

between 500 and 1000 (43%) and the small MFIs comprising less than 500 members

(14%).

The MEC SAPP of Tattaguine, the MEC FAM of Dakar and the MEC

Koyli Winrdé of Podor hold the highest membership levels (1253, 1232 and

1178 members respectively) subsequent to their seniority in the field combined

with their targeting strategies. Indeed, MEC SAPP and MEC FAM are the only

ones holding other periodic branch aside from their headquarters.

The MEC MFR of Malicounda shows up the lowest membership (326)

due likely to its youth in the industry given that it is the only one MFI with

headquarters in Malicounda. Nevertheless, the propinquity of the MEC with other

MFIs in Mbour might also induce a low membership record since the other MFIs

are developing new targeting strategies such as mobile services points.

The membership levels recorded at the MEC UGPN of

Daroukoudoss, the CREC of Méckhé and the MEC MFR of

Pékesse pinpoint their anchorage within their communities and the

willingness of their mother associations to assist them.

On the other hand, three main categories of members are

identified: Women, Men and Groups or development associations. In general, the

membership is dominated by women (representing 50% of members) followed by men

(42%) and groups (8%). This finding reasserts Armendariz (2011) who argues that

women usually constitute the main clients/members of MFIs.

Nevertheless, this trend presents specificities. For example

at Malicounda, Daroukoudoss and Meckhé, men are the most likely (with

49% and 64 % of membership respectively) albeit with tiny differences. In

contrast, MEC FAM members are more likely women (76%) because the first

women-oriented approach at the beginning.

It seems interesting to notice that overall, the membership is

growing over time. For the entire seven MFIs, the growth rate in 2010 was about

23% which is sharply higher than the average of the country (8.7%) for the same

period (MEF/DRSSFD, 2010). Nevertheless, the trend decreases in 2011 with 3% of

growth mainly owed to the decrease in membership at the MECs of Daroukoudoss

and Koyli Winrdé and at the CREC of Méckhé. Three main

reasons might explain this decrease: the competition in Mboro region (for the

MEC of Daroukoudoss), the sanitazing of the accounting of the CREC of

Méckhé, and the temporary cease of the FAIR in 2010.

4.3.3 Delivering flexible financial services

4.3.3.1 Savings

Notwithstanding the widespread understanding that poor people

especially living in rural and remote areas do save in different ways (Mersland

& Eggen, 2007), there is nowadays increasing evidence that monetary savings

in banks or MFIs are growing tremendously.

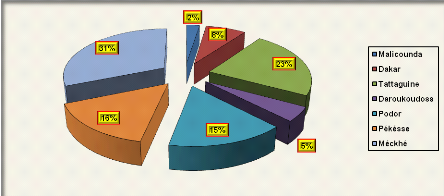

The figure 5 depicts the contribution of each MFI in savings

mobilization in 2011.

Figure 5: MFIs contribution

to the network saving mobilization in 2011

Source: Our survey (may-august

2012)

It appears from the figure 5 that in 2011, the CREC UGPM of

Méckhé and the MEC SAPP of Tattaguine contributed both for about

54% of the network savings meaning an uneven ability of savings mobilization

amongst the seven MFIs.

Besides, the savings growth rate recorded by the seven MFIs in

the last three years is about 14.5% with some variations between MFIs.

The increasing savings at the MEC SAPP (annual average growth

of 18%) is peculiarly vindicated by its targeting strategy based on periodic

service points and the mandatory savings' requirements before loans granting

(33% of the loan).

In contrast, despite the high annual average savings growth at

the MEC MFR of Malicounda of about 29%, its contribution to the entire MFIs is

about only 2% in 2011. This situation can be explained not only by the

malfunctioning of its mother-association, but also by the difficulties of the

MFI to meet its members' financial needs. For example fewer loans were granted

in 2008 and 2009.

If similar savings growth tendency is witnessed at the MEC

Koyli Winrdé of Podor (average growth of 31%), it is not the case of MEC

FAM of Dakar (6%) showing tremendous difficulties for collecting savings. On

the other hand, the MEC FAM of Dakar recorded very low amount in savings with

low contribution to the network (8%) owing to a prior situation of bad

financial governance especially in 2009 leading to a crisis of confidence

between staff, board members and the MFI members, despite of the creation of a

periodic service point.

The savings amount collected at the CREC Méckhé

entailing its noteworthy contribution to the network (31%) is chiefly boosted

by the mother association (Union des Groupements de Producteurs de

Meckhé) and the economic interest grouping KAYER (Kayor Energie Rural)

which have opened accounts in the MFI for financial transactions with their

members or clients respectively.

Overall, the savings collected can be gathered in three main

categories:

- The demand deposits. It is the most dominant savings product

(in average 53% of total deposits) over the last four years for all the seven

MFIs.

- Term deposit: it is interest bearing deposit in favour of

depositors. In most of the MFIs, the interest varies from 3 to 5% with maturity

of 3 to 7 months for short term deposits and more than 12 months for long terms

deposits.

- Compulsory savings: in all the MFIs surveyed, the compulsory

savings is one on the requirement to have access to credit. It replaces

tangible collateral and helps MFIs mitigate credit risk as the provision of

collateral assets in rural areas is very tricky. In general, the compulsory

savings vary between 10 and 25% except in the MEC SAPP where the compulsory

savings is about 33%.

Likewise, some periodic compulsory savings are collected from

the members in the MEC FAM of Dakar and MEC Koyli Winrdé (FONGS

FINRURAL, 2011).

4.3.3.2 Credit

Loan products

Mainly focused on rural financing, surveyed MFIs extend

miscellaneous loan products to meet their members' financial needs.

The figure 6 gives an overview of the importance of two main

products in 4 MFIs (Tattaguine, Méckhé, Koyli Wirndé and

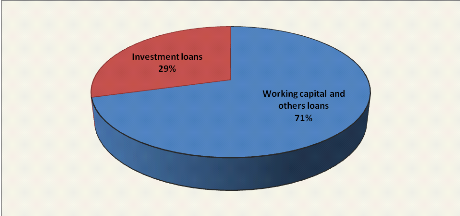

Pékésse) in 2011.

Figure 6: Split of loan

products in 4 MFIs in 2011 as % of the GLP

Source: Our survey (may-august

2012)

The main loan product delivered is the seasonal credit or

working capital loan which helps farmers finance their basic activities. This

loan terms, varying according to the MFIs, depend essentially on the targeted

groups with a maturity betwixt 6 and 15 months and usually a bullet repayment

in capital and interest. Likewise, the charged nominal interest rates are

comprised between 15% and 25%.

If these terms seem common, it appears important to evince

some specificity. For example, the MFI of Pékésse caters 4

variants of the seasonal credit regarding loan maturity and including cattle

fattening (6 months), agriculture, vegetable production, poultry farming (8

months), and staple food storage (7 months). Small business such as retail

sales, handcrafts, agricultural food processing also benefit from working

capital loans with different maturity.

The second most important loan product is the investment loan

with very low interest rate over 12 to 48 months. These kinds of long term

loans over 3 years have increased tremendously from 9% to 28% between 2005 and

2010 in Senegal (MEF/DRSSFD, 2010). All the seven MFIs are experiencing this

innovative product through the support of the «Fonds d'Appui aux Iniatives

Rurales» (FAIR)16(*)

which finances agricultural, commercial and handcrafts long term investments

such as material, land management etc...without tangible collateral, the loan

applicant mother association constituting the moral guarantee. As for the

seasonal credit, loan terms (maturity, repayment schedule) are discussed with

the borrowers based on the FAIR method which includes small project devising.

The interest charged by the FAIR is about 4% for MFIs. In return MFIs are

allowed by the FAIR agreement to charge a maximum interest of 12% with no

compulsory savings regardless the MFI. Therefore, MFIs can make a maximal

margin of about 8% on the investment loans in other to sustain their social

action toward their members.

Many other loan products exist and are specific to each MEC,

depending on the operating area and the real needs of the targeted population.

Those loans include energy loans, consumption loans, and education credits,

express or emergency loans.

Credit policies and Loan size

Whereas for regulated MFIs, involving in credit delivery

supposes the enforcement of well devised credit policies in order to prevent

drifts and subsequently ensure a better credit risk management, the situation

seems quite paradoxical at FONGS FINRURAL. Indeed, only one of the surveyed

MFIs hold a procedure manual thus hampering the accuracy and the dedication to

loan granting processes. Nonetheless, credit committees and the staff members

have empiric knowledge about the products supplied and their

characteristics.

The average duration for a loan application approval is one

month in most of the MFIs except for emergency loans; this because some MFIs

require a minimum number of loan applications for the credit committee to

sitting whilst credit committee of other sits in a monthly base. Acknowledging

that for efficiency purposes the maximum duration for a microfinance loan

approval should be less than 30 days, it can be deduced that the current

situation in the MFIs might undermine good credit policy practices.

The loans size varies between MFIs from 5000 FCFA and 5000000

FCFA and depends on the type and the object of the credit. The MFI of

Meckhé recorded the highest average loan size (455000 FCFA) over the

last four years.

For all the loans, no tangible asset is asked to people as

guarantee. The main guarantee is the compulsory saving and the minimum capital

requirement or savings requirement in the demand deposits account.

Is there a risk of cash flow cycle

mismatch?

The overall remark is that besides the investment credit for

which the repayment schedule is split in frequent instalments after one year or

6 months, the others loans are mainly repaid in bullet. If those repayment

policies do meet with most of MFIs members, it appears important to stress out

that granting always more than 3 months maturity loans with a balloon repayment

could jeopardize MFIs. Indeed, the fact to apply yearly or semi-annual

instalments may undermine borrowers' incentive to repay back their loans

(Buchenau, 2003), thus breaking down the loan repayment culture. Likewise,

repaying loans at once in fine in capital and interest may not be affordable

for borrowers especially when they cannot get their revenue at once.

Another aspect that should be underscored is the loan

diversion, specifically the use of seasonal credit for shorter cash flow cycle

activities. In Podor for example some beneficiaries invest their seasonal

credit in their retail sales, restaurants, handcrafts activities. The mismatch

between the disbursement/reimbursement of the loans and the cash flow cycle of

households might increase the loan delinquency and MFIs' turnovers accordingly.

For Bédécarrats, Baur & Lapenu (2011), the bankruptcy of

number of microfinance institutions due to important customers drop out and to

the increase in arrears show up that MFI don't always provide adapted financial

services such as credit.

When can a loan be adapted? Is it when it meets members' needs

or when its terms fit the cash flow of households?

For the common understanding and numerous scholars such as

Pearce, Goodland & Mulder (2004) and Collings, Morduch, Rutherford &

Ruthven (2009), a financial product, particularly the credit is adapted not

only when it is affordable but also when it is flexible, meaning that

disbursement / reimbursement periods meet with the cash flow cycles of

households.

In agriculture financing especially, flexible credits are crux

elements for a well attainment albeit they are likely to worsen loan portfolios

and imply liquidity management issues17(*).

It is therefore on the responsibility of MFIs and their

members to find out the balanced situation which will not put at risk MFIs

operations while fulfilling rural households' needs.

4.3.4 Sources of funding

The surveyed MFIs rely on three main sources of funding: the

deposits, the equity and the borrowings.

71% of MFIs rely on deposits as main source of funding which

contributed in 2011 for 38%, 42%, 53%, 48% and 50% of the financial structures

of MFIs of Malicounda, Dakar, Tattaguine, Pékesse and

Méckhé severally. This situation corroborates the legal status of

these MFIs to collect first savings then to redistribute them as credit. For

the 29% remaining, their main source of funding is borrowings with 50% and 59%

for MFIs of Podor and Daroukoudoss respectively.

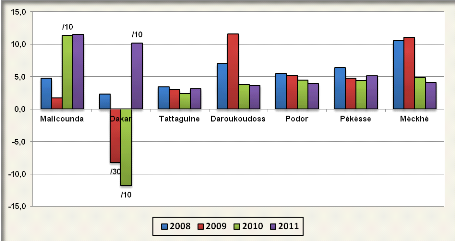

The figure 7 hereafter shows the borrowing capacity of the

MFIs.

Figure 7: Leverage

(Debt/Equity)

/X: The real value is X times de value on the

figure

Source: Our survey (may-august

2012)

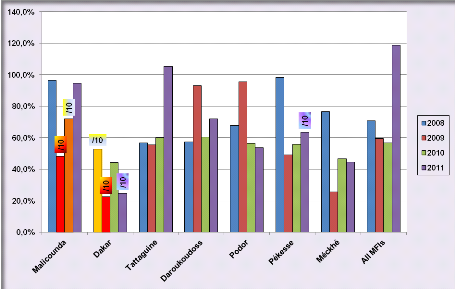

The analysis of the figure 7 reveals that at the MFI of Dakar

(MEC FAM) the leverage ratio varied tremendously from high negative ratios in

2009 and 2010 to a highly positive figure in 2011. The negative figures in 2009

and 2010 are mainly due to the loss in equity during those periods. The equity

itself has been influenced by the negative figure of retained earnings over

years. The highly positive ratio in 2011 entails that the MFIs is borrowing

more than it should and might jeopardize its depositors albeit the decrease in

savings mobilization. Indeed, for Périlleux (2010), the higher the

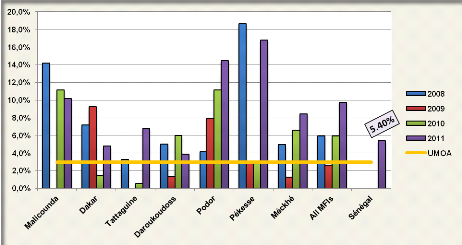

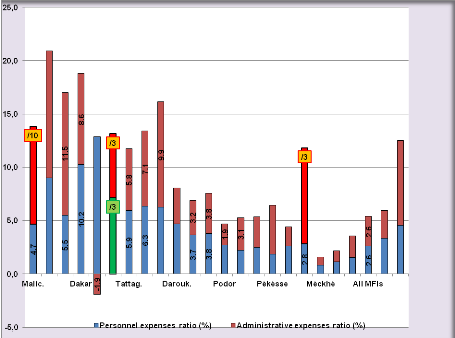

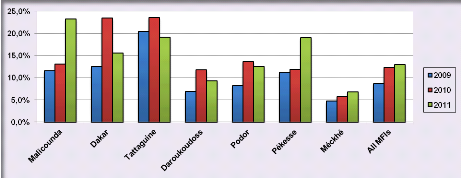

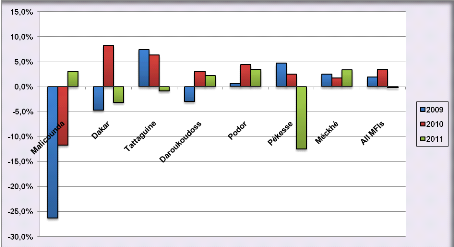

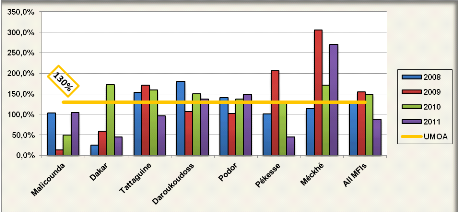

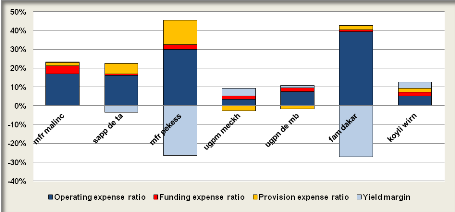

external financing, the more borrowers prevail, thus threatening savings and