|

ASSESSMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKERS INCENTIVES ON

MATERNAL AND NEWBORN HEALTH SERVICES PERFORMANCE,

IN RWINKWAVU DISTRICT HOSPITAL,

KAYONZA DISTRICT, RWANDA

NDANGURURA DENYS

MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH

AUGUST, 2015

ASSESSMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKERS INCENTIVES ON

MATERNAL AND NEWBORN HEALTH SERVICES PERFORMANCE,

IN RWINKWAVU DISTRICT HOSPITAL,

KAYONZA DISTRICT, RWANDA

NDANGURURA DENYS

11/MPH/KA/G/050

A Thesis Submitted to Bugema University in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Award of the Degree of Master of Public Health

AUGUST, 2015

ACCEPTANCE SHEET

This thesis entitled «ASSESSMENT OF COMMUNITY

HEALTH WORKERS INCENTIVES ON MATERNAL AND NEWBORN HEALTH SERVICES PERFORMANCE,

IN RWINKWAVU DISTRICT HOSPITAL, KAYONZA DISTRICT, RWANDA .»

Prepared and submitted by NDANGURURA DENYS in partial

fulfilment of the requirements of MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH, is

hereby accepted.

Beth Sigue, PhD

Paul Katamba, PhD

Member, Advisory Committee Member, Advisory Committee

_______________________

_____________________

Date Signed Date Signed

Sylvia T. Callender-Carter, Dr PH

Chairperson, Advisory Committee

__________________________

Date Signed

Assoc. Prof. Nazarius M. Tumwesigye

Jaji Kahinde, MBA

Member, External Examining Committee Member, Internal

Examining Committee

________________________

______________________

Date Signed Date Signed

Accepted as partial fulfilment of the requirement for the degree

of MASTER PUBLIC HEALTH, Bugema University

Sylvia T. Callender Carter, Dr PH

Chairperson, Department of Public Health

_____________________

Date Signed

Paul Katamba, PhD

Dean, School of Graduate Studies

_____________________

Date Signed

DECLARATION

I, NDANGURURA Denys, hereby, declare that the thesis entitled

«Assessment of Community Health Workers Incentives on Improving

Maternal and Newborn Health Services, Case Study of Rwinkwavu District Hospital

in Kayonza District, Rwanda», is my personal

original work and to the best of my knowledge, it has not been submitted, in

part or in a whole, for any degree in any university.

Signature--------------------------------

NDANGURURA Denys

Date------------------------------------

DEDICATION

With love, this thesis is dedicated to my beloved family for

their love, care and support during my studies. To all friends and relatives

who contributed to this research.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH

The writer was born September 10th, 1983 in Nzige

Sector, Rwamagana District in Eastern Province of Rwanda. He is born to Mr.

Andre NDANGUZA and Madeleine KAMAHE. He completed his primary school at Akanzu

Primary School, Rwamagana district. In 1996, he joined APEGA secondary school

where he completed O' level. Then after from 2000 to 2003 he completed his

studies from the school of Agriculture and Veterinry in Veterinary studies. In

September 2003, he joined the Universté Ouvrte/Campus de Goma in RDC and

in 2006, he got the advanced Diploma in General Nursing then after in the same

institution from 2006 to 2008 he completed his undergraduate studies in Public

Health getting a bachelor degree in Public Health. He then worked at Rwinkwavu

district hospital as a nurse then after he worked in the same institution as

the professional in charge of Community Health Program from 2007 to 2014. He is

now a District Coordinator for Rwanda Family Health Project, a USAID funded

project working with Rwanda through the Ministry of Health to improve family

health services. In January 2012, he joined the school of graduate school at

Bugema University, a Chartered Seventh Day Adventist Higher learning

Institution for Master degree in Public Health at Bugema university, Kampala,

Uganda which he completed in July 2015.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I must convey my deepest appreciation to my chief

supervisor Dr Sylvia Callender -Carter and my supervisors Dr. Beth Sigue and

Dr. Paul Katamba, who gave me valuable guidance, support. Also the

encouragement from Dr. Rhoda Kayongo and Dr. Moses Kayongo the good will from

the initial to the final stage of helping me to develop an understanding of

this paper. Your advice has played by Stephan S. Kizza. is an outstanding role

in shaping this paper. Your comments and observations were vital inputs which

enabled me to improve this paper.

It is a pleasure to express my gratitude to my colleagues for

helping me and sharing experiences and discussing courses.

My special thanks to my wife, sons, parents, brothers and

sisters for their priceless support.

May God bless all of you!

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

PAGE

LIST OF TABLES

x

LIST OF FIGURES

xi

LIST OF APPENDICES

xii

LIST OF ABREVIATION

xiii

ABSTRACT

xiv

CHAPTER ONE

1

INTRODUCTION

1

Background of the Study

1

Statement of the Problem

3

Research Questions

5

General Objective

6

Specific Objectives

6

Hypothesis

6

Significance of the Study

6

Scope of the Study

7

Limitation of Study

8

Theoretical Framework

9

Conceptual Framework

10

Operational Definitions of Terms

10

CHAPTER TWO

13

LITERATURE REVIEW

13

The Context of Community Health Workers

13

Community Health Workers' Incentives in Rwanda

15

Provision of Equipment

18

Compensating CHWs and Perdiem as an Incentive

20

Membership in CHW's Cooperatives

22

Maternal and New Born Health Services

23

PAGE

Relationship between CHWs Incentive and Improve

Maternal and Newborn Health

24

Summary of Identified Gaps

25

CHAPTER THREE

28

METHODOLOGY

28

Population of Study

28

Sample Size

28

Sampling Procedure

29

Research Instruments

30

Validity

30

Reliability

31

Data Collection Procedure

31

Data Analysis

32

CHAPTER FOUR

33

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

33

Demographic Characteristics of Research

Participants

33

Level of Community Health Workers incentives

36

Relationship between CHW's Incentives and

Performance of Maternal and Newborn Health Services

40

CHWs Financial Incentives on Performance of MNH

41

Membership in CHWs Cooperatives on Performance of

MNH

42

CHAPTER FIVE

44

SUMMARY, CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

44

Summary

44

Conclusion

46

Recommendation

47

REFERENCES 48

48

APPEND ICES

52

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE

PAGE

Table 1: Showing Incentives and Desincentives

CHWs

23

Table 2: The Number of Population Sample

29

Table 3: Social-Demographic Characteristics of

Respondents

34

Table 4: Level of Community Health Workers

incentives

37

Table 5: Level of Maternal and Newborn Health

Service

39

Table 6: Logistic Regression of Community Health

Workers Related incentives and Performance Maternal - Newborn Health Services

in the Study Area

41

LIST OF FIGURES

FIGURE

PAGE

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework

10

LIST OF APPENDICES

APPENDIX

PAGE

Appendix 1: Questionnaire

52

Appendix 2: Data Collection Letter

55

Appendix 3: Acceptance Collection Letter

56

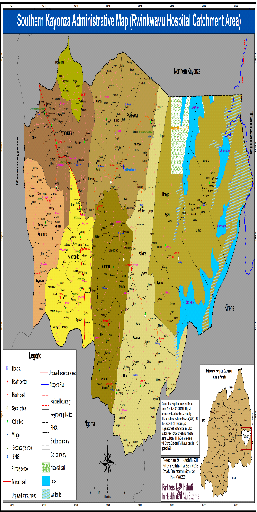

Appendix 4: Geographical Map of Rwinkwavu District

Hospital

57

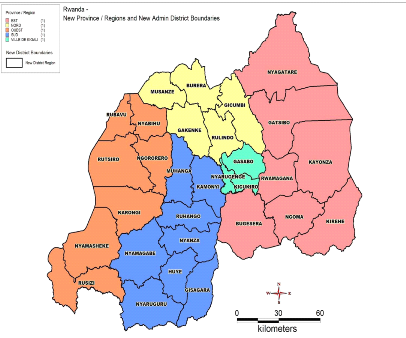

Appendix 5: Map of Rwanda Showing Kayonza District

where Located Rwinkwavu District Hospital in South

58

LIST OF ABREVIATION

CBHPP: Community Based Hygiene Promotion Program

CBNP: Community Based Nutrition Program

CHC: Community Hygiene Club

CHWs: Community Health Workers

DHS: Demography and Health Survey

HC: Health Center

ICCM: Community Case Management

IMCI: Integrated Management of Childhood Illnesses

KMC: Kangulo Mother Care

MCHIP: Maternal Child Health Integrated Program

MGDs: Millennium Development Goal

MMR: Maternal Mortality rate

MNHC: Maternal and New Borne Health Care

MOH: Ministry of Health

MUAC: Measurement Upper Arm Circumference

PBF: Performance Based Financing

RUTF: Ready to use Therapeutic Food

SAM: Severe and Acute Malnutrition

UNICEF: United the Nation of Child Fund

USAID: United States Agency of International development

WHO: World Health Organization

WFP: World Food Program

ABSTRACT

Denys NDANGURURA, School of Graduated Studies, Bugema University,

July, 2015. Thesis title; «ASSESSMENT OF COMMUNITY HEALTH

WORKERS INCENTIVES ON MATERNAL AND NEWBORN HEALTH SERVICES IN RWINKWAVU

DISTRICT HOSPITAL, KAYONZA DISTRICT, RWAND''A.

Chief Supervisor: Sylvia Callender -Carter, Dr.

PH

The study was carried out on assessment of Community Health

Workers Incentives on Maternal and newborn health services performance. The

sample size was 236 CHWs in charge of MNH distributed in eight health centers

of Rwinkwavu district hospital catchment area. To determine the demographic

characteristics of respondent, the researcher used descriptive statistics. It

revealed that the majority of them 125(53.2%) are those in the age range of 36

to 50 years. All respondents are women that are why when you look at gender

236(100%) were women. The marital status shows that the married are the

predominant among other represented by 168 (71.1%). The level of education the

majority of respondents 151(64.0%) have is primary. Most of the CHWs in charge

of MNH are agro-farmers 193(81.8%) distributed as cultivators 91(38.6%),

farmers 55(23.3%) and the farmers-cultivators represented 47(19.9%). The level

of CHWs incentives was showed a low mean and standard deviation ( =1.75; SD = 0.82). The results on MNH services performance the study was

showed a moderate mean and standard deviation of ( =1.75; SD = 0.82). The results on MNH services performance the study was

showed a moderate mean and standard deviation of ( = 3.04; SD = 1.26). = 3.04; SD = 1.26).

Logistic regression was used to establish influence of CHWs

incentives on performance of them in MNH services. CHWs financial incentives to

be high are about 3 times as likely to perform in maternal and newborn health

services (P=0.012, (1.26-6.26),UR=2.808) however result indicate that being a

member of CHWs cooperative is not a significant predictor of performance of

CHWs in MNH services(P>0.05

The study recommends reviewing the system of CHWs performance

based financing system on equal opportunity and strong monitoring and

evaluation based on mentorship of CHWs cooperatives.

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

Background of the Study

Globally community based intervention true CHWs is in urgent

need to improve health of women and children, particularly in areas of Africa,

where Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) 4 and 5 are most lagging. This

requires strong community engagement and formal investments in national health

systems, especially for those least likely to be reached through current

national health strategies, such as those in rural communities. Community

Health Workers (CHWs) have been internationally recognized for their notable

success in reducing morbidity and averting mortality in mothers, newborns and

children. CHWs are most effective when supported by a clinically skilled health

workforce, particularly for maternal care, and deployed within the context of

an appropriately financed primary health care system. However, CHWs have also

notably proven crucial in settings where the overall primary health care system

is weak, particularly in improving child and neonatal health. They also

represent a strategic solution to address the growing realization that

shortages of highly skilled health workers will not meet the growing demand of

the rural population. As a result, the need to systematically and

professionally train lay community members to be a part of the health workforce

has emerged not simply as a stop-gap measure, but as a core component of

primary health care systems in low resource settings, Prabhjot Singh (2011).

A National Roadmap to Accelerate the Reduction of Maternal and

Infant Mortality was adopted by the Rwandan Ministry of Health in 2008. The

roadmap outlines approaches to reducing maternal and newborn mortality, and

includes strategies for improving the quality of the facility based primary and

referral care, the availability of Kangaroo mother care (KMC) and the

availability of community-based services for women during pregnancy and in the

post-natal period.

According to the Roadmap builds on the National Reproductive

Health Policy and the National Child Health Policy (2008), and the Strategic

Plan for Acceleration of Child Survival (2008-2012), all program activities are

implemented in the context of the Economic Development and Poverty Reduction

Strategy of Rwanda (EDPRS 2008-2012) and the National Health Sector Strategic

Plan (Rwanda HSSPII 2009-2012).

General approaches to implementing community-based

activities are outlined in the National Community Health Policy of Rwanda

(2007). The health system in Rwanda is decentralized to the district level.

The country is divided into 4 provinces and the City of Kigali, 30 districts,

416 sectors, around 9,000 cells and 15,000 Imidugudu (villages). A system of

community-based health insurance in the form of mutual health insurance was

established in 1996. Since 2006 Rwanda has implemented a Performance Based

Financing (PBF) model to provide incentives to facility-and community-based

health workers. The PBF approach provides quarterly remuneration to health

workers based on performance measured by defined indicators (MOH Rwanda,

2012).

In order to improve the performance of CHWs and

obtain good results on agreed upon indicators especially the maternal and

infant mortality, payments are made when proof of an agreed level of

performance is attained. Every month at the Health Center level data is

collected from reports on indicators and entered into a web-based database

(SisCom). The Sector Steering Committee oversees the evaluation of different

indicators during a quarterly meeting and approves the payment to the CHW

Cooperatives. This quarterly C-PBF accompanied with monthly top ups and

trainings are the major and in some cases the sole incentives provided to CHWs

as a motivation to achieve their different and important tasks (MOH, Rwanda

2009).

Statement of the Problem

Community health workers (CHWs) are

increasingly recognized as a critical link in improving access to services and

achieving the health-related Millennium Development Goals. Given the financial

and human resources constraints in developing countries, CHWs are expected to

do more without necessarily receiving the needed support to do their jobs well.

How much can be expected of CHWs before work overload and reduced

organizational support negatively affect their productivity, the quality of

services, and in turn the effectiveness of the community-based programs that

rely on them.

Even if the MOH provides different incentives like monthly top

up, Community PBF, Trainings, Provision of materials and equipment's to

Community Health Workers in order to improve the service they gave in maternal

and newborn health services, the objectives of MOH are not yet achieved:

According to the DHS (2010), report indicated the persistent

high maternal mortality rate where out of 100,000 women that gave birth 476

deaths occurred within 42 days. According to MDGs this indicator must be

reduced to 268/100,000 by 2015. Where the evolution of this indicator was:

· 2000:1071/100.00 lives birth (DHS 2000)

· 2005:785/100.000 lives birth (IDHS2005)

· 2008:540/100.000 lives birth (Rwanda HMIS 2008)

· 2010: 476/100.000 lives birth (RDHS2010)

· 2015: 210/100.000 lives birth (DHS 2014/2015)

In 2008, with the introduction of community based maternal

and newborn health implemented by motivated CHWs in charge of maternal and

newborn health up to now we are observing the improvement in maternal health

where the current statistics shows 210/100,000 lives birth (Rwanda, DHS

2014/2015) and our study is assessing if there a contribution of CHWs in charge

of MNH on improving maternal and newborn health services. Rwanda is observing

also an improvement in fertility ration where 6.1(DHS2005), 5.5(RIDHS200-2008),

4.6(DHS2010) and 4.2(DHS2014/2015) since the past ten years. Birth occurred in

health facilities by skilled provider have been improved in last fifteen years

from 27% in 2000 to 91% in 2015. The figures before 2008 and after 2008 with an

introduction of community based maternal and newborn health implemented by

motivated CHWs in charge of maternal and newborn health shows 27% (RDHS2000),

28% (RDHS2005), 45% (RIDHS2007-2008), 69% (RDHS2010) and currently 91%

(RDHS2014-2015).

By 2015, Millennium Development Goal 5 (MDG 5) sets a target

of 75 percent reduction in maternal mortality, from 400/100,000 live births to

100/100,000 between the 1990 baseline and 2015. Although progress has fallen

short of achieving this MDG by 2015, every region of the world has made

important gains, and globally, maternal mortality has fallen by 45 percent over

the past two decades (WHO, 2014).

In April 2014, the World Health Organization, Maternal Health

Task Force, United Nations Population Fund, USAID and the Maternal Child Health

Integrated Program, and representatives from 30 countries agreed on a global

target for a maternal mortality ratio (MMR) of less than 70/100,000 live births

by 2030, with no single country having an MMR greater than 140. This will

require that we collectively build on past efforts, accelerate progress and

ensure strong political commitment from all stakeholders (WHO, 2014).

Research Questions

The study attempted to answer the following

questions.

1 What is the Socio-demographic characteristic of community

health worker in charge of maternal and newborn health?

2. What are the community health workers in charge of maternal

and newborn health incentives?

3. What is the level of maternal and newborn health services?

4. Is there a significant influence between Community Health

Worker's incentives on performance of maternal and newborn health services?

General Objective

The general objective was to assess the relationship between CHWs

in charge of MNH incentives to performance of maternal and newborn health services.

Specific Objectives

1. To determine the demographic characteristics of respondent

CHW's in charge of maternal and newborn health.

2. To determine the level of CHW's in charge of maternal and

newborn health incentives.

3. To determine the level of performance of maternal and

newborn health services.

4. To establish the relationship between CHW's in charge of

maternal and newborn health incentives and performance maternal and newborn

health services.

Hypothesis

There is no relationship between CHWs in charge of MNH

incentives and performance maternal and newborn health services.

Significance of the Study

The study is significant to the community, CHWs and health

providers within Rwinkwavu District Hospital. The overall health sector

(Ministry of Health, NGOs and the Rwandese Government) will be benefit from the

results in Rwinkwavu District Hospital, Rwanda.

CHWs: The findings of this study will help

Community Health Workers to actively participate in maternal and newborn health

improvement and they will be aware at which level they contribute in that

improvement referring to the incentives they receive from different partners.

Public: The public will benefit from this

research because the improved maternal and newborn health services will

contribute to the reduction of maternal and newborn mortality rate with social

economic growth.

Policy Makers and Government: The findings

will promote leaders of Rwinkwavu District Hospital, Kayonza District, Ministry

of Health and NGOs to advocacate the way of incentivizing CHWs which may

promote income generating activities of CHWs cooperatives and sustainability of

the program. It will make recommendations to the district, Ministry of Health

and partners involved in national maternal and newborn health to improve their

policies and guidelines.

Researchers: The findings will stimulate the

interest of other researchers to carry out more empirical studies in order to

set up strategies to improve maternal and newborn health with the greater way

of incentivizing the CHWs in charge of maternal and newborn health.

Scope of the Study

Rwinkwavu District

hospital catchment area is located in Kayonza District in the Eastern Province

of Rwanda. It is boarded by the Gahini and Mwiri Sectors of Kayonza District in

the north, Kirehe and Ngoma District in south, United Republic of Tanzania in

the East and Rwamagana District in the West. It has 8 administrative sectors, 8

health centers, 33 cells, 251 villages dispatched on a surface of 64.5 square

kilometers and the population of 194248 (Rwanda

HMIS, 2015).

The study was conducted in its 8 health centers which are

Rwinkwavu, Cyarubare, Ndego, Nyamirama,Kabarondo, Karama, Rutare and Ruramira

health centers. The research was concentrated on CHWs in charge of maternal

and newborn health incentives and improvement of maternal and newborn health

services that that was accomplished from January, 2015 to July, 2015 (Rwanda

HMIS, 2015).

Limitation of Study

The major limitation of

this study was the unwillingness of some respondents to give true information

during data collection as it was intended to investigate the contribution of

incentives they receive on improvement of services they deliver to mothers and

newborns. Probing and encouragement was done by the researcher to divulge the necessary information to

respondents.

The findings from this

study was arguably limited by the fact that the study cannot claim to be truly

nationally representative because the study was conducted to CHWs in charge of

maternal and newborn health of only one district hospital among 46 district

hospitals country wide.

Theoretical Framework

The study was based on Maslow's Theory of Human Motivation.

This framework will contain aspects of other psychological theories of

motivation, corporate management models, and volunteer management models.

Applying Maslow's theory to existing corporate management models were

established the theory's relevance to management structures. Because volunteer

work differs from corporate work, the Theory of Human Motivation was adapted to

non-paid, volunteer work.

The framework was applied to major areas of existing CHW

programs in order to review the incentives, and ultimately, the incentives in

place. The goal of incentive structures should be to motivate CHWs to complete

their tasks effectively, while ensuring that they will stay committed with the

intervention. Motivation can be achieved in many ways, either extrinsically or

intrinsically. In analyzing an intervention, it is important to distinguish the

types of incentives motivating CHWs in charge of maternal and newborn health,

because they reflect the sustainability of the

program that can contribute to an improvement of maternal and newborn

health.

Conceptual Framework

Independent Variable

Dependent Variable

Maternal and newborn Health Services

performance

o Percentage per target

Community Health Workers Incentives

o Financial incentives of CHWs

o Non-financial incentives of CHWs' (equipment and materials)

o Membership in CHW's cooperatives

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework

Operational Definitions of

Terms

Community PBF: is mechanism of CHWs

motivation through their performance based financing. Payments made when proof

of the agreed level of performance, Community PBF guide details management at

different levels, the Sector Steering Committee oversees the implementation and

approves payment to the CHW Cooperative. Indicators entered at HC level into

web-based database after quarterly approval by committee with feedback.

This was measured by analyzing the level of agreement from one

to four meaning that: strongly agree (SA) = 4, agree (A) = 3, strondly disagree

(SD) = 2 then disagree (DA) = 1.

Provision of Equipment and Materials: The

community health workers in charge of maternal and newborn health are provided

with different tools and materials from government of Rwanda and different

partners local and international those help them to accomplish their tasks

those are bags, umbrella, timer, thermometer, balance, mobile phone, rain cost,

register for information recording, reporting register and the register for the

in reproductive age and pregnancy women. This was measured by analyzing the

level of agreement from one to four meaning that: strongly agree (SA ) =

4,agree (A) = 3, strongly disagree (SD) = 2 then disagree (DA) = 1.

CHWs Monthly Perdiem: This amount most of the

time paid by partners to strengthen the self-motivation based on monthly home

visits, daily accompaniment & key maternal health activities, timely

completion of a monthly report. This was measured by analyzing the level of

agreement from one to four meaning that: strongly agree (SA) = 4, agree (A) =

3, strongly disagree (SD) = 2 then disagree (DA) = 1.

Income Generation for Membership in CHW's

Cooperatives: All CHWs are organized in cooperatives and everyone is

supposed to benefit income generation from cooperative project. This was

measured by analyzing the level of agreement from one to four meaning that:

strongly agree (SA) = 4, agree (A) = 3, strongly disagree (SD) = 2 then

disagree (DA) = 1.

Maternal and Newborn Health Services: are the

tasks the CHWs in charge of maternal and newborn health are assigned to

accomplish. Those are almost 12 indicators seen in this research questionnaire.

The respondents gave the number then the surveyors made percentage after the

mean of measuring scare was calculated.

This variable was be measured using the scale as

follow:6=81-100% interpreted as high or very good performance, 5 = 61-80%

interpreted as good performance, 4 = 41-60 % interpreted as moderate or neuter

performance , 3 = 20-40% interpreted as low or poor performance, 2 = less than

20% very poor performance then after 1 is interpreted as not any activity

accomplished.

.

CHAPTER TWO

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Context of Community Health

Workers

The global policy of providing primary level care was

initiated with the declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978s. The countries signatory to

Alma Ata declaration considered the establishment of CHW program as synonym

with Primary Health Care approach (Mburu, 1994; Sringernyuang Hongvivatana,

& Pradabmuk, 1995). Thus in many developing countries PHC approach was seen

as a mass production activity for training CHWs in 1980s (Matomora, 1989).

During these processes the voluntary health workers or CHWs were identified as

the third workforce of «Human resource for Health» (Sein, 2006).

Following this approach CHWs introduced to provide PHC in 1980s are still

providing care in the remote and inaccessible parts of the world (WHO, 2006a).

The CHWs have evolved with community based healthcare

programme and have been strengthened by the PHC approach. However, the

conception and practice of CHWs have varied enormously across countries,

conditioned by their aspirations and economic capacity. This review identified

seven critical factors that influence the overall performance of CHWs which are

discussed in this section. In discussing these issues, our aim is to (a)

highlight certain empirical knowledge and (b) point out, if any, gaps in the

design, implementation and performance of CHWs(Prasad BM, Muraleedharan

VR2007).The above review highlights several aspects to be kept in mind in

designing and implementing effective CHW schemes. The review emphatically shows

that (a) the selection of CHWs from the communities that they serve and (b)

population-coverage and the range of services offered at the community levels

are vital in the design of effective CHW schemes. It should be noted that

smaller the population coverage, the more integrated and intensive the service

offered by the CHWs(Prasad BM, Muraleedharan VR2007).

Despite advances in reaching remote communities, there are

many opportunities for improvement and expansion of CHW programs, especially

related to the development of new tools and evidence-based policy to

«guide global health policy and implementation.» This is where the

One Million Community Health Workers (1mCHW) Campaign comes into play. By

coordinating existing CHW programs with African governments, and making it

clear where the core interests of local and global organizations fit into

national frameworks, 1mCHW is developing the tools necessary to guide CHW

policies. Moreover, 1mCHW is developing an «Operations Room,» an

online dashboard to provide comprehensive information about CHW activities on

the ground. The «Operations Room» will chart progress in different

countries and contain the compiled evidence demanded by the article's authors

to deepen our understanding of CHW programs and of the most effective means of

implementation.We know the plan works: a comprehensive review of CHW literature

conclusively conveys the effectiveness of CHW programs, especially given the

recent access to mobile technologies. 1mCHW will help turn this promising

literature into life-saving results on the ground(One million community health

workers campaign2013).

In the study conducted by USAID (2010) on Community Health

Worker Programs: A Review of Recent Literature, the research concluded that key

components were identified as central to the design and implementation of

functional and sustainable CHW programs: defined job description with specific

tasks or responsibilities for volunteers, recognition and involvement by local

and national government, Community involvement (especially in recruitment and

selection, by making use of existing social structures, consider cultural

appropriateness, address needs of community, etc.), resource availability

(funding, equipment, supplies, job aids, etc.).

Monitoring and evaluation of programs , linkages with formal

health care system training (including refresher trainings), supervision and

feedback, incentives or motivational component and advancement opportunities

which are all similar to this research.

Community Health Workers'

Incentives in Rwanda

Performance-Based Financing is thoroughly embedded in the

Rwandan Health system. It is practiced in health centers and district hospitals

nationwide using common approaches. Ministry of Health Performance-Based

Financing has started at the central ministerial level (Basinga, 2009).

Performance-Based Financing systems are being designed for the

national Community Based Health Insurance system, and for the CDLS. A national

model for Community Performance-Based Financing has been developed, using a

broad consultative process. The model is based on experience gained during the

implementation of the health center and hospital Performance-Based Financing

models, and benefits from a close fit with these models. The purpose of this

Community Performance-Based Financing (PBF) Guide is to document the tools and

processes used in Community PBF. This guide is primarily meant as a background

document for trainers, sector PBF Steering Committee members, and the Community

Health Worker Cooperatives. However, it will be used by all working in the

Rwandan Health System (Basinga, 2009).

The community PBF is not for individual performance

remuneration. The purpose of the incentive is for community health workers to

increase the capital of their cooperatives. The cooperatives on their turn will

then start income generating activities to the benefit of the individual

members. The remuneration of individual community health workers will be from

the profit of the cooperative activities (MOH Rwanda, 2009).

Resource poor countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa,

face many challenges improving maternal health due to financial and human

capital constraints, lack of motivation among health providers and lack of

physical resources. One of the key policies implemented in Rwanda in response

to these issues is Performance Based Financing (MOH Rwanda, 2009).

PBF provides bonus payments to providers for improvements in

performance measured by indicators of specific types of utilization (e.g.

prenatal care) and quality of care. While the approach promises to improve

health system performance, there is little rigorous evidence of its

effectiveness, especially in low-income settings.

This study examines the impact of the incentives in the

Rwandan PBF scheme on prenatal care utilization, the structure and process

quality of prenatal care, institutional delivery, and modern contraceptive use.

The analysis uses data produced from a prospective quasi-experimental design

nested within the program's rollout. The rollout was implemented in two phases:

in 2006, 86 facilities (treatments) in rural areas enrolled in the PBF, and

another 79 facilities (control) enrolled two years later.

In order to isolate the incentive effect from the resource

effects, the control facilities were compensated by increasing their

traditional budgets with an amount equal to the average PBF payments to the

treatment facilities. Baseline and end line data were collected from all of the

facilities and a random sample of 14 households in each facility's catchment

area.

Using a different approach, PBF had a large and significant

impact on the quality of prenatal care measured by process indicators of the

clinical content of care and deliveries in facilities. However, no such effect

was found on prenatal care visits or on the use of modern contraceptives (MOH,

Rwanda2009).

The results provide evidence to support the hypothesis that

financial performance incentives can improve both the use and quality of

maternal health services. Policy recommendations include increasing incentives

for prenatal care service, complementary training to increase quality and

combining PBF with a demand-side intervention such as conditional cash transfer

involving community health workers (Basinga, 2009).

In the study conducted by JSI (2009), on the ''Non-financial

incentives for voluntary community health workers'' they concluded the

following: Community acceptance for voluntary CHWs and their own attitudes to

their work is generally positive. Nevertheless, continual efforts to enhance

recognition and understanding of their voluntary work in the community are

needed to maintain their morale. Their work was also found to be very `doable'

and expectations from them quite clear. The teaching materials and the support

provided to them by HEWs in the form of monthly meetings and work visits can be

further strengthened however.

The motivations of voluntary CHWs, in terms of their reasons

for being involved in their work and the benefits they expected, were strongly

characterized by their desire to promote health in their community including

themselves and their families. Steps taken to enhance their efficacy in this

regard will therefore have a positive impact on their motivation levels.

Volunteers were also strongly motivated by the responsibility and acceptance

they received from the community, as well as the recognition, respect,

credibility and political status they have gained. Conversely, they were

sometimes discouraged by misunderstanding of their voluntary role on the part

of the community. VCHWs can therefore be further motivated by promoting

community understanding and recognition of their work. Their aspirations for

learning and employment opportunities can also be considered in relation to

ways of sustaining volunteerism.

Provision of Equipment

The community health workers are provided with different tools

and materials from government of Rwanda and different partners local and

international witch help them to accomplish their tasks. They have Arthemeter

Lumefatrin (Primo) for treatment of Malaria and rapid diagnosis test (RDT) to

confirm Malaria; they have amoxicillin for pneumonia with a timer to count

respiratory frequency, zinc and oral rehydration solution (ORS) against

diarrhea and RUTF for malnutrition.

There are equipped also with monitoring and evaluation tools

for data recording and reporting with innovation of Rapid SMS with cell phones

for tracking the first 1,000 days of life, preventing unnecessary mother and

new born death in Rwanda. They have also boots, torches and radios. The cell

coordinator has bicycles, MOH, Rwanda (2011).

Community health workers need access to the proper equipment

and supplies to deliver expected services. This requires procurement of

supplies on a regular basis to avoid any substantial stock out periods.

Community must be equipped with a steady stock out of supplies and commodities

needed for their day to day operations.

Community health workers also need materials to support their

mobility, with reliable and safe transportation between households (such as an

umbrella or bicycles as appropriate in a given context) and backpacks for

supplies (Lehmann et al. 2007).

Community health training and deployment without immediate

continuous and reliable supplies to accomplish task is inefficient demotivating

and damaging to community health workers credibility (Lehmann et al. 2007).

Therefore, a functional community health workers system

requires a robust supply management chain, with a keen eye to transport and

drug supply, as well as reliable supply chains for all other equipment required

by community health workers to perform their job functions. Reliable and

sustainable supply chain systems are a challenge for large scale primary health

care and community health programs in general (WHO, 2010).

In Pakistan, each lady health worker should have a supply kit

that includes contraceptives and essential drugs in order to perform her work.

These community health workers are resupplied each month at their local clinics

(Muhamood et al. 2010).

A research conducted in Rwanda on community based provision of

family planning services revealed that one of the major barriers mentioned by

CHWs and supervisors was the difficulty of keeping all the required materials

in stock. CHWs reported that since they receive only 2 - 3 units of each method

of family planning that they sometimes quickly ran out of stock. CHWs often

live far from the HC that resupplies them. CHWs are required to go to the HC to

retrieve commodities and consumables but they are not given a means of

transport (Rwanda Ministry of Health, 2011).

In Zambia, a large community health worker program in Kalabo

District almost completely collapsed. Key reasons identified were a shortage of

drugs and community health workers' selection criteria. Furthermore, the

authors found that the community members in charge of CHWs selection knew

little about selection criteria. Further quality of supervision was poor and in

50% cases nonexistent (Stekelenburg et al. 2003).

Compensating CHWs and

Perdiem as an Incentive

This an amount most of the time paid by partners to

strengthen the self motivation based on monthly home visits, daily

accompaniment and key maternal health activities, timely completion of a

monthly report form and participation at monthly training. This perdiem is

between10 to 20$ depending on performance of community health workers

qualitatively and quantitatively (MOH, Rwanda 2011).

Compensating CHWs has a number of important benefits for both

the health care program and the communities it serves. First payment for

meaningful work provides a needed income for those in resource limited

setting.

Secondly, compensating CHWs can strengthen their roles as an

essential member of the clinical team, thereby creating a stronger bridge

between the community to the clinic or hospital based setting. Third, payment

particularly when it is a fair wage and paid on time can serve as a source of

motivation for CHWs in performing their work reliably and effectively. Fourth,

payment can also increase the amount of time CHWs are available on a weekly

basis, can prevent turnover, and can promote program consistency.

Finally, investment in CHWs can potentially increase uptake in

medical services, promoting adherence to HIV and TB medication and resulting in

long term improved health outcomes in the community (MOH, Rwanda 2011).

Compensation structures will vary by country and

program. Find out whether there are labor regulations that affect compensation

in addition to any minimum or maximum wage requirements or other regulations,

when budgeting for the CHWs program. Some programs either choose to or are

mandated to cap salaries at the same level as those paid to schoolteachers or

other civil servants. In some contexts, CHWs are paid a baseline salary and are

then given an incentive bonus for each sick community member they see. In other

places, CHWs receive compensation through a cooperative, whose members pool

their funds to support it and equal control over its operation. Additionally

many systems involve performance based financing, in which CHWs receive

compensation following the completion of certain responsibilities such as

monthly home visits or the accurate collection of household data (MOH, Rwanda

2011).

CHWs who have a higher skill level, such as those that work

with patients with MDR/TB may receive a higher monthly salary compared with

CHWs who are responsible for more general outreach (MOH, Rwanda 2011).

In Haiti, women's health workers are compensated

more than the typical CHW due to the greater knowledge base necessary to carry

out their work. When planning a compensation structure, consider if and how

CHWs will be paid , whether or not they will receive bonuses, top - up, or

other financial incentives. If CHWs receive payment, determine how much they

will receive and the schedule of payment (Healthy villages 2002). Types of

payment may include: money for meals, transportation, income from the sales of

products, monthly stipend, monthly salary, performance based financing, cash

for task, access to membership in a cooperative (Healthy villages 2002).

Membership in CHW's

Cooperatives

CHWs cooperatives membership: All CHWs organized are in

cooperatives to ensure income generation and accountability of expected

results. Community PBF payments used for cooperative income generating projects

include: poultry, cattle/goat/pig rearing, crop farming, basket making, etc

that improves performance of CHWs by motivating them to rise agreed upon

performance indicators, the payments made when proof of the agreed level of

performance. The Sector Steering Committee oversees the implementation and

approves payment to the CHW Cooperative (MOH, Rwanda, 2011).

The study done by Havard School (2011), on CHWs in Zambia

entetle'' incentives design and management it shows incentives and

desincentives summirized in below :

Table 1: Showing Incentives and

Desincentives CHWs

|

Motivation factors

|

Incentives

|

Disincentives

|

|

Monetary incentives that motivate CHWs

|

Ø Satisfactory numeration, materials incentives,

financial incentives

Ø Possibility of future payment

|

Ø Inconsistent remuneration

Ø Change in tangible incentives

Ø Inequitable distribution of incentives among different

CHWs

|

|

Nonmonetary incentives that motivate CWHs

|

ü Community recognition

ü Acquisition of valued skills

ü Personal growth and development

ü Accomplishment

ü Peer support

ü Preferential treatment

ü Clear role

|

ü CHWs from outside of the country

ü Inadequate refresher training

ü Inadequate supervision

ü Lack of respect from HFs a staff

|

|

Community factors that motivate CHWs

|

ü Community involvement selection

ü Community organizations that support CHWs

ü Community involvement in CHWs training

ü Community information system

|

ü Inappropriate selection of CHWs

ü Lack of community involvement in CHWs selection, training

and support.

|

|

Factors motivate communities to support and stain CHWs

|

Ø Visible change

Ø Contribution to the community empowering

Ø CHWs associations

Ø Successful referral to health facilities

|

Ø Unclear role and expectation(preventive versus curative

care)

Ø Inappropriate CHWs behavior

Ø Failure to take community need into account

|

|

Factors that motivate MOH staff to support and sustain

CHWs

|

Ø Policy and legislation to support

Ø Visible change

Ø Government community finding for supervisory

activities

|

Ø Inadequate staff and supply

|

Maternal and New Born

Health Services

Community Health Workers identify and register women of

reproductive age (encourage family planning,), identify pregnant women and

encourage ANC, birth preparedness and facility based deliveries, identify women

and newborns with danger signs and refer them to health facility for care,

accompany women in labor to health facilities, encourage early postnatal

facility checks for both newborns and the mothers and report those activities

by using Use Rapid SMS (MOH, Rwanda 2011).

Relationship between CHWs

Incentive and Improve Maternal and Newborn Health

Working with the community gives

health workers a platform from which to strengthen their relationship with the

community and receive community feedback, as well as a structure for regular

interaction with health facility staff. Community participation is an integral

part of CHWs' incentives. Without involvement, communities lack interest and

expectations, leaving CHWs without a support system we can't achieve MDGs 4 and

for improving maternal and child health (MOH, Malawi, 2014).

The rate of decline in child mortality is too slow in most

African countries to achieve the Millennium Development Goal of reducing

under-five mortality by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015. Effective strategies

to monitor child mortality are needed where accurate vital registration data

are lacking to help governments assess and report on progress in child

survival. They present results from a test of a mortality monitoring approach

based on recording of births and deaths by specially trained community health

workers in Malawi (MOH, Malawi, 2014).

Results from systematic reviews of CHW program confirm that

CHWs provide critical links between rural communities and the formal health

system and have been shown to reduce child morbidity and mortality when

compared to the usual healthcare services (MOH, Sierra Leone 2013).

With appropriate support and sufficient training, CHWs can

potentially play a pivotal role in strengthening health systems in areas with

poor human resources for health. More specifically, they are an important

resource for implementing interventions targeting reductions in neonatal

mortality and tracking women throughout their pregnancy while simultaneously

promoting appropriate maternal and newborn care practices (MOH, Sierra Leone

2013)..

Their potential however, is hampered by inadequate

supervision, lack of locally relevant incentive systems, loss of motivation,

insufficient recognition and community support, poor connectivity to health

facilities, and knowledge retention problems. Moreover, higher attrition rates

are often observed in programs where CHWs are asked to volunteer.

The motivation of CHWs and the risk of high attrition rates

therefore have important implications for the effectiveness, success, cost,

credibility and continuity of CHW-based programs, (MOH, Sierra Leone 2013).

Summary of Identified

Gaps

We now know that CHWs can play a crucial role in broadening

access and coverage of health services in remote areas and can undertake

actions that lead to improved health outcomes, especially, but not exclusively

in the field of child and maternal health. CHWs represent an important health

resource whose potential in providing and extending a basic health care to

underserved populations must be fully tapped. Despite the experience with

community health workers worldwide, the research gap remains in community

health worker literature especially in terms of Incentives strategies

and maternal and infant mortality improvement (MOH, Rwanda

2011).

Despite the availability of Rwandan community health policy

and strategies there is no study conducted on contribution of CHWs' incentives

on the improvement of maternal and infant health services. The evaluation done

by MOH, Rwanda (2011), where the main objective was to assess the quality of

services provided by the CHWs and their access to necessary supplies. This was

mainly assessing what CHWs do and how they give services but this didn't relate

to the quality of services provided in terms of maternal and infant health with

incentives they get. The study was conducted in the district of Djenné,

Mali by Perez in 2009, concerning the role of community health workers in

improving child health programs which mainly compared the knowledge and

practice between households with and without community health workers.

The researcher mentioned the results in terms of

knowledge/practices the family with CHWs might have but didn't relate the

incentives given to CHWs to their contribution on infant and maternal health

(MOH, Rwanda 2011).

The study conducted by Winch et al., (2001) was assessing the

contribution of CHWs on improvement of health system including drug

availability and the skills of Community Health Workers to assess, classify,

and treat children accurately. This included the three following elements:

improving partnerships between health facilities and services and the

communities they serve, increasing appropriate and accessible care and

information from community-based providers, integrating promotion of key family

practices critical for child health and nutrition but they didn't asses the

relationship between CHWs' incentives and maternal and infant health

improvement.

In all the literature above there is no specific research,

which explains well the assessment of incentives given to CHWs to their

contribution on improving maternal & newborn health. Hence, for the purpose

of this study, the research intends to assess the relationship between CHWs' in

charge of maternal and newborn health incentives on improvement of maternal and

newborn health services. Child health intervention

that warrants considerably more attention, particularly in Africa and South

Asia. (Oxford University Press, 2005).

CHAPTER THREE

METHODOLOGY

This

Chapter gives the procedure that was used in this research so as to achieve the

set of the study objectives. The researcher adopted cross-sectional survey

design. The researcher adopters both qualitative and quantitative approach. The

researcher also adopted correlational research design to find the relationship

between the two variables.

Population of Study

The study was conducted in eight health centers of Rwinkwavu

District hospital in Kayonza District of Rwanda those are Rwinkwavu, Ndego,

Cyarubare, Nyamirama, Karama, Rutare, Kabarondo and Ruramira health centers.

The total target population of this study was 236 CHWs in charge of MNH working

in HCs catchment areas presented as follow: 38 CHWs from Rwinkwavu, 45 CHWs

from Cyarubare, 27 CHWs from Ndego, 26 CHWs from Nyamirama, 38 CHWs from

Kabarondo, 7 CHWs from Rutare, 28 CHWs from Karama and 27 CHWs from

Ruramira.

Sample

Size

The sample consisted of eight health centers and the selection

was based on the number of CHWs in charge of MNH in health center catchment

area. Considering the number of CHWs in charge of MNH the sample was drawn to

be 236 target population and the sample size calculation is based on the simple

random sampling method because all population was subject of the study; this

was used because it is applicable for academic research and it is more helpful

when data collected for the whole population is available. The sample size in

each health center has been calculated based on proportionate allocation

sampling technique by Kothari (2004). Ni = n .NJ/N.

Where n = sample size of entire target population, NJ = number

of population of each health center and N = total number of target population,

ni = sample size of every health center.

Sampling Procedure

The target population of the study was 236

respondents. Morgan and Krejcie (1970), recommend that if a

researcher has a target population of 236, the sample size for

the study is 236. Therefore the study sample size was

236 respondents, the probability methods gave us simple random

sampling to be applied because the whole population is available and easily

participated in responding to the questionnaire given by the researcher.

Table 2: The Number of

Population Sample

|

NO

|

Health Centre

|

Total Population

|

Sample size

|

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

Rwinkwavu

|

38

|

n1= 263.38/236 = 38

|

|

2

|

Cyarubare

|

45

|

n2= 236.45/236 = 45

|

|

3

|

Ndego

|

27

|

n3 = 236.27/236 = 27

|

|

4

|

Nyamirama

|

26

|

N4 = 236.26/236 = 26

|

|

5

|

Ruramira

|

27

|

N5 = 236.27/236 = 27

|

|

6

|

Kabarondo

|

38

|

n6 = 236.38/236 = 38

|

|

7

|

Ruatare

|

7

|

N7 = 236.7/236 = 7

|

|

8

|

Karama

|

28

|

N8 = 236.28/236 = 28

|

|

TOTAL

|

|

236

|

Source: Rwanda

community HMIS, 2015

Research Instruments

Data

collection was carried out by using a questionnaire; that questionnaire was

designed in English and the researcher translated directly into Kinyarwanda.

The questionnaire is divided into three sections: Section A which includes

Socio- demographic characteristics of respondents, section B is based on the

closed ended question which is in accordance with the second objective by

materials or equipment received and section C is questions related to the third

objective evaluating the rate of accomplishment of target. The objectives one

was measured using descriptive statistics and was interpreted using

percentages. Objectives two and free was measured and interpreted using mean

and standard deviation while objective four was interpreted using simple linear

regression.

Validity

It indicates the extent to which an instrument measures what

it is supposed to measure. Six experts in the field have checked the

questionnaire for the consistency of the items, conciseness, intelligibility

and clarity. The checking of items, consistence, relevance, clarity and

ambiguity; pretesting was done in two health centers that were not part of the

target population.

Their input helped to ensure that the

instrument measured adequately what it is intended to measure. The researcher

used CVR (Content Validity Ratio) where the expert will agree with the items.

The formula to be used is: CVR = (E -N/2) / (N/2)

Where E: number of who rated the object or

person in question; N: total number of expert. CVR can measure

between -1.0 and 1.0. The closer to 1.0 the CVR is, the more essential the

object is considered to be. Conversely, the closer to -1.0 the CVR is, the more

non-essential it is.

The research instrument was valid when the CVR is 0.6 or above

indicated the extent to which an instrument measures what it is supposed to

measure. A supervisor was always consulted for checking the items, consistence,

relevance and clarity.

Reliability

Twenty CHWs from Kabarondo Health center were randomly

selected for testing research instrument, the estimation of reliability will be

ascertained by a pilot testing of the instrument and applying Cronbach's Alpha

coefficient by means of a Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Gal,et

al,2009). Cronbach's Alpha coefficient will be used to measure internal

consistency of the research tool. The instrument are reliable when the results

of twenty respondents give an alpha coefficient of > 0.7 (Gal, et al,

2009).

Data Collection

Procedure

The researcher obtained a letter of introduction from Bugema

University, Graduate school to the Director of Rwinkwavu District Hospital. The

researcher submitted the letter in person to the office of Rwinkwavu District

Hospital Director and upon authorization; the researcher made an appointment

through the community health workers in charge of health center level to

confirm when he could visit to collect data as community health workers

involved in this study live in different areas. The questionnaire was given to

the respondents after ensuring them that the information given will be kept

confidentially and would be used only for academic and research purpose.

The researcher ensured voluntary participation of respondents

to be clearly informed about the objective and benefits of the study, the

confidentiality of records was protected and no name of respondents were asked

during the data collection.

Data Analysis

After a successful data collection exercise, the researcher

coded and entered data, tabulated and interpreted the findings. For

quantitative data, the computer package, SPSS was used to analyze and interpret

the data. Descriptive statistic including frequency and percentage was used to

answer objectives one, the mean and standard deviation was used to answer the

objective two and three. Linear regression logistic was used to analyze the

objectives four that was to establish the influence of incentives on improving

maternal and newborn health services. Descriptive statistics allowed the

researcher to reduce bias and estimate sampling errors and precision of the

estimates derived through statistical calculation. Data collected from the

document analysis was analyzed manually and results were used to supplement and

support the findings from the main instrument.

CHAPTER FOUR

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

This chapter presents the result of the study and their

discussion in line with research objectives. This discussion of the study

result was done while comparing the present research findings with those of

previous and recently related research studies. Still in discussing the study

results, the findings were used to answer the research questions from which the

objectives of the study evolved.

Demographic Characteristics

of Research Participants

The first research objective included

236 respondents, and in the course of data collection, the research succeeded

to collect all the questionnaires, that is; there was no questionnaire which

represented an error of omission. Descriptive statistics, mainly frequency and

percentages, were used to analyze data on objective one which was to find out

the demographic characteristics of the respondents in term of age, gender,

marital status, education background and occupation.

The entire respondents were women because in Rwandan community

health policy the CHWs in charge of newborn and maternal health are the women.

The frequency and percentage were meant to establish the most frequently

occurring responses and the least frequently occurring response.

The Table 3 presents the summary of findings, showing the

socio-demographic information of the respondents to the study which demonstrate

age, gender, marital status, education background and occupation in order to

know more information about the improvement of MNH services compared to the

incentives they get.

Table 3: Social-Demographic

Characteristics of Respondents

|

Item

|

Categories

|

Frequency

|

Percent

|

|

Age

|

15-19

20-35

36-50

51-60

|

2

106

125

3

|

0.8

44.9

53.2

1.3

|

|

Gender

|

Females

|

100

|

100

|

|

Marital status

|

Single

Married

Widow/Widower

Divorced

|

7

168

60

1

|

3.0

71.2

25.4

0.4

|

|

Educational level

|

No-formal Primary

Secondary

Post-secondary

|

1

151

69

14

|

0.8

64.0

29.2

5.9

|

|

Occupation

|

No job

Farmer

Cultivator

Farmer cultivator

Professional

Trading

|

4

55

91

47

11

28

|

1.7

23.3

38.6

19.9

4.7

11.9

|

Source: Primary data

Age: the findings on age range of CHWs in charge of maternal

and newborn health revealed that the majority of them 125 (53.2%) are those in

age range of 36 to 50 years followed by those of 20 to 35 represented by 106

(44.9%).

Gender: the category of 15 to 15 and 51 to 60 has the lowest

number of respondents as indicated by table 3. All respondents are women that

are why when you look at gender 236 (100%) were women.

Marital status: the marital status in this table shows that

the married are the predominant among other represented by 168 (71.1%) then

widow/Widower 60 (25.4%), one was divorced and 7(3.0) were single.

Education: the level of education was assessed in other to

test the knowledge of the respondents where we have found that the majority of

respondents 151 (64.0%) have primary level education, 69 (29.2) represent those

who have accomplished the secondary school level of education, 14 (5.9%) had

done post-secondary education and only one who had not accomplished the primary

school.

Occupation: most of CHWs in charge of maternal and newborn

health are in agriculture business; where 91(38.6%) are cultivators, 55(23.3%)

are the farmers, 47 (19.9%) are the farmers-cultivators, 28 (11.9%) are

traders, 11 (4.7%) are in professional employment and 4 (1.7%) are reported

jobless.

In this line with the research findings of Global Journal of

health Science (2012), on effect of social-demographic characteristics of CHWs

on performance of home visit during pregnancy where it was ascertained that

there was a significant relationship between age group than other and good

record with tasks performance.

Contrary to my research where the Rwandan Community health

policy put in place only women for follow-up of maternal and newborn health

this research conducted by Global Journal of health Science (2012), shows that

the male have a positive record more than the female while females were more

likely to counsel and enable their clients. That is why they have been choose

by Rwandan government to fill the position of CHWs in charge of maternal and

newborn health than their lower literacy level counterparts. Global Journal of

health Science (2012), concludes by emphasizing on reasons why the

Socio-demographic characteristics of community health workers affect the

performance of home visits in various ways. The study also confirmed that CHWs

with lower literacy levels satisfy and enable their clients effectively. Also

in the study conduct by Bagonza J et all, 2014, they find that females are

performing well.

In this study also, due to the policy in place which

emphasizes that all CHWs must accomplish at least primary school education and

above that is why their level of education mainly indicated 151(64.0%) who

accomplished primary school, 69(29.2%) have a secondary certificate, well as 14

(5.9%) have post-secondary education and only one among all respondents had not

accomplished primary school.

In the study conducted on Community Health Workers: Essential

to Improving Health in Massachusetts; 66% of respondents hold some form of

community college, college or university degree. Of the CHWs, 60% reported

holding some form of degree beyond high school. 19.2% had attended some college

level courses beyond high school. 12.5% hold a high school degree or its

equivalent, and only 4% do not hold a high school degree or its equivalent

(Massachusetts 2005).

Level of Community Health

Workers incentives

In results as indicated in Table 4 in this study involved

three sub variables which are both monetary and non-monetary incentives grouped

in three categories such as: first the community performance based financing

(CPBF) and incentives which they receive every after quarterly evaluation by

sector steering committee.

Secondly, the provision of equipment and materials for

facilitating the accomplishment of their assigned duties, and thirdly,

membership in community health workers cooperatives for income generation with

mentorship for capacity building.

Table 4: Level of Community Health

Workers incentives

|

Item

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Interpretation

|

|

Community financial incentives

|

|

|

|

|

Receiving sufficient salary after monthly target visits

|

1.55

|

0.79

|

Low

|

|

Receiving incentive of monthly bonus

|

1.93

|

1.05

|

Low

|

|

Receiving quarterly incentive of BPF

|

1.94

|

0.73

|

Low

|

|

I receive a bag

|

1.63

|

0.90

|

Low

|

|

I receive umbrella

|

1.79

|

1.14

|

Very low

|

|

I receive rain coat

|

3.35

|

0.98

|

High

|

|

Register book for monthly reporting

|

1.95

|

1.25

|

Low

|

|

Register book for pregnant women/productive age

|

1.03

|

0.22

|

Very low

|

|

Register of follow up for pregnancy women

|

1.05

|

0.32

|

Very low

|

|

Receiving training and follow-up

|

1.28

|

0.71

|

Very low

|

|

Conducting monthly inventory based on my store card

|

2.39

|

1.35

|

Low

|

|

Advice to clients (referral) to use health facility

services

|

1.06

|

0.37

|

Very low

|

|

Aggregate mean and SD

|

1.75

|

0.82

|

Low

|

|

CHWs' non-financial incentives (equipment and

materials)

|

|

|

|

|

Timer equipment for respiration count

|

1.19

|

0.65

|

Very low

|

|

Mobile Phone equipment

|

1.24

|

0.74

|

Very low

|

|

Thermometer equipment

|

1.20

|

0.69

|

Very low

|

|

Weighing scale equipment

|

1.09

|

0.48

|

Very low

|

|

Measurement of upper arm circumference equipment

|

2.35

|

1.48

|

Low

|

|

Aggregate mean and SD

|

1.41

|

0.81

|

Very low

|

|

Membership in CHW's cooperatives

|

|

|

|

|

Receive quarterly supervision from health facility

|

1.45

|

0.78

|

Very low

|

|

Receive per-diem during the monthly meetings

|

2.71

|

1.08

|

Moderate

|

|

Member of community health workers' cooperative

|

1.09

|

0.40

|

Very low

|

|

Receive 30% of quarterly PBF from my cooperative

|

1.45

|

0.79

|

Very low

|

|

Access loans from my cooperative

|

3.14

|

1.18

|

Moderate

|

|

Aggregate mean and SD

|

1.97

|

0.85

|

Low

|

|

Grand Mean

|

1.71

|

0.82

|

Low

|

Source: Primary data

Legend: 1.00-1.49 (Very low); 1,

50-2.49 (Low); 2.50-3.49 (Moderate); 3.50-4.49 (High); 4.50-5.00 (Very

high)

Table 4 therefore, shows the study results on the community

performance based financing (CPBF) and incentives showed that there was low

mean and standard deviation ( = 1.75; SD = 0.82) well as on CHWs' equipment and materials the results

showed a very low mean and standard deviation ( = 1.75; SD = 0.82) well as on CHWs' equipment and materials the results

showed a very low mean and standard deviation ( =1.41; SD = 0.81) lastly, membership in community health workers

cooperatives for income generation with mentorship for capacity building the

result showed a low mean and standard deviation ( =1.41; SD = 0.81) lastly, membership in community health workers

cooperatives for income generation with mentorship for capacity building the

result showed a low mean and standard deviation ( =1.97; SD=0.85) . The general result on community performance based

financing and other incentives showed also a low mean and standard deviation

( =1.97; SD=0.85) . The general result on community performance based

financing and other incentives showed also a low mean and standard deviation

( =1.71; SD=0.82). =1.71; SD=0.82).

This is in line with the research findings of WHO Regional

office for Africa (2013), which shows that the total catchment population for

the 31 health centers in 2010 was 720 40814. Of these, 4.1% (29 537) were

expected to be women in need of maternal health services per annum.

The antenatal care indicator (visit before or during 4th month

of pregnancy) was targeted to reach at least 30% of women in 2010 or 738 women

per month.

The indicator on delivery was targeted to achieve 85% of women

delivering in health facilities. The postnatal indicator was targeted to reach

15% of women in 2010.

Level of Maternal and Newborn Health Service

performance

Furthermore, the third object research objective showed in

table 5 was to determine the findings on level of maternal and newborn health

in Rwinkwavu district hospital in Rwanda.

Table 5: Level of Maternal and

Newborn Health Service

|

Item

|

Mean

|

SD

|

Interpretation

|

|

Census of women in reproductive age

|

1.57

|

0.92

|

Low

|

|

Visit 3 times all pregnancy women in the village

|

1.55

|

0.99

|

Low

|

|

Women visited in first prenatal care visits to homes

|

2.86

|

1.58

|

Moderate

|

|

Women visited by CHWs during pregnancy

|

2.47

|

1.43

|

Low

|

|

Women who completed 4 standards ANC

|

3.42

|

1.44

|

Moderate

|

|

Deliveries at health facilities by health professionals

|

2.60

|

1.68

|

Moderate

|

|

Home deliveries

|

4.63

|

0.91

|

Very high

|

|

Home deliveries referred to health facility

|

4.91

|

1.95

|

Very high

|

|

Women presented in postpartum consultation within

|

4.28

|

1.24

|

High

|

|

Women vaccinated against tetanus during pregnancy

|

1.72

|

1.14

|

Low

|

|

Women receive iron for anemia to prevention

|

1.61

|

1.15

|

Low

|

|

At risk pregnancies referred to health facility

|

4.85

|

0.69

|

Very high

|

|

Grand mean and SD

|

3.04

|

1.26

|

Moderate

|

Source: Primary data

Legend: 1.00-1.49 (Very low);

1,50-2.49 (Low); 2.50-3.49 (Moderate);3.50-4.49 (High);4.50-5.00 (Very

high)

The result revealed a moderate mean and standard deviation of

( =3.04; SD = 1.26). In the article, `Rwanda's Success in Improving

Maternal Health', strategies that were used to reach the success story of

maternal mortality (a decrease of 77% between 2000 and 2013 in

Rwanda's

maternal mortality ratio currently at 320 deaths per 100,000 live births,

under-5 child mortality reduced by more than 70 percent), Worley (2015),

identified the factors that created this story. Among them were maternal

health as a priority in postwar rebuilding, maternal and child health core of

community-based health insurance, and family planning key to sustained success

in maternal health. However, some challenges were identified among which was

the need for 586 more midwives to reach 95 percent skilled birth attendance. =3.04; SD = 1.26). In the article, `Rwanda's Success in Improving